Bundeswehr: Navy strengthens presence in the Baltic Sea: What sailors need to know

Fabian Boerger

· 12.06.2025

It's mid-October and the scene in Neustadt Bay could be straight out of a Hollywood film. A German navy tender is moored where sailors bustle in summer and the Scandinavian ferries commute day in, day out. The grey colossus, a supply ship for other naval units, looks like a container freighter that is too short. It lies there calmly, as if it wants to merge with the panorama of the nearby coast.

Suddenly, the roar of an engine can be heard. It comes closer quickly. Just a few seconds later, a sports plane breaks away from the grey sky. Like a bird of prey, it swoops down on the supply ship, only to turn away at the last moment. As soon as the plane has left, the warship abruptly starts to move.

It's impressive how quickly thousands of tonnes of steel can be set in motion. Again and again, the supplier changes course. It seems to react to the attacker from the air like a hare making hooks. Because it is back and is about to take another nosedive. What is missing to complete the picture of a Hollywood film is the thundering of guns. But they are silent on this day. The supposed air raid is an exercise, not an emergency.

Naval exercise manoeuvre in Neustadt Bay

There is a reason why manoeuvres like this take place in Neustadt Bay: the navy's Damage Prevention Training Centre is located on land; one of the many training areas is located off the coast. This is where ship crews prepare all year round for deployment in the event of war.

A spokesperson for the German Navy explains that the so-called combat training includes training for "external combat", in which, for example, aircraft or speedboats simulate the attack. Internal combat, on the other hand, involves practising how to react to an enemy hit or a fire below deck, for example.

From "turning point" to "the situation is serious"

Viewed from a sailing boat through the lenses of binoculars, the exercise is a spectacle. At the same time, however, it leaves a bland aftertaste. It symbolises what politicians and experts have been proclaiming for months. Cue "turning point" and "the situation is serious". It also raises the question of how sailors should behave in such a case. After all, one would think that encounters with warships along the German Baltic coast have recently increased.

But has the number of navies really increased? Or has the view of the grey fleet merely changed and is it now perceived more consciously? Above all, how should skippers act if they come close to a warship or even unexpectedly get caught up in an exercise?

The Baltic Sea - sailing area versus naval manoeuvring area

The starting point is February 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine. Since then, the Baltic Sea has become the scene of a hybrid conflict. The inland sea is much more than just a leisure oasis and popular sailing area. On the one hand, there are the transport routes. Hundreds of freighters and tankers start their journey into the world from here. On the other hand, there is a variety of infrastructure on, near and under the sea. Wind farms, for example. Or thousands of kilometres of electricity and internet cables, oil and gas pipelines that run along the bottom of the Baltic Sea. Several dubious incidents have shown just how vulnerable these and other facilities are.

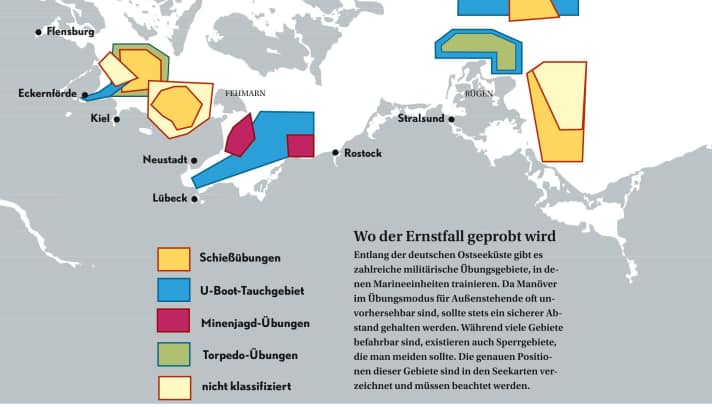

The naval training areas along the German Baltic coast are located here:

Shadow fleet, spy ships and sabotage

One of these occurred on Christmas Day 2024 and involved the "Eagle S", an oil tanker from the so-called shadow fleet. This refers to ships that Russia uses to circumvent international sanctions. In the Gulf of Finland, the tanker dropped anchor at full speed and damaged the "Estlink 2" submarine cable. It supplies Estonia with electricity from Finland. Both countries regard the incident as an act of sabotage, controlled by Russia.

There are also unusual cases of ships drifting alongside pipelines or power lines for long periods without a localisation signal. According to the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, they scout the critical infrastructure. European security services assume that there are hundreds of such Russian spy ships.

The problem is that under international maritime law, coastal states cannot simply stop activities outside their territorial waters. The list of such unusual incidents could go on and on. It illustrates why security authorities repeatedly emphasise the need to be vigilant.

German Navy ready for an emergency

The German naval forces recently adapted their strategy. In mid-May, they presented the "Naval Course 2035" in Berlin. The concept includes specific measures derived from the experiences of the war in Ukraine. Deterrence is a component of this strategy. It also emphasises rapid operational readiness and the use of new technologies, among other things. Moscow should be able to see this: Germany is ready for an emergency.

And it's not just Moscow that is noticing this. Many sailors have also long since noticed that ships from the navy and allied states have become more present in this country. This is intended to demonstrate operational readiness, says Martin Schwarz, frigate captain and former commander of the Navy's 3rd Minesweeper Squadron. However, this presence is not designed for escalation.

"We react to actions that occur and show that we are monitoring the situation and can act if necessary." Frigate Captain Martin Schwarz

Schwarz explains that more ships are regularly travelling throughout the Baltic Sea. However, this does not mean that the number of German naval vessels has also increased. In fact, this has actually decreased in recent years. According to Schwarz, the feeling that more ships are travelling is partly due to increased public interest. "I have the impression that sailors are now paying closer attention to what the navy is doing, where and how."

DSV: Great interest in correct handling

Rainer Tatenhorst also deals with this topic time and again. He is Head of the Cruising Sailing Department at the German Sailing Association (DSV). "During on-site appointments at sailing clubs, our employees are almost always asked about the topic of the navy in the Baltic Sea." However, the number of enquiries is limited. But there is a great need to find out about the right way to deal with it. Tatenhorst: "Sailing crews need to be aware of what is happening in their sailing area at all times."

However, not every naval vessel you come across is involved in defence against acts of sabotage or espionage. "The ships that patrol off the coast are not the ones that sailors have much to do with," says Schwarz. In most cases, it is naval units that train for emergencies.

This is the case in the Bay of Kiel, off Rügen and especially in the Bay of Lübeck. Navy training areas are located there. They are marked accordingly on the nautical charts.

"Sailors must always be aware of what is happening in their sailing area. Therefore, always switch on the radio!" Rainer Tatenhorst, DSV

Exercise mode not always obvious

However, exercises are not always recognisable as such. "Even I sometimes can't recognise what they're doing," says frigate captain Schwarz. For example, naval vessels in exercise mode may not behave as they would under normal conditions. They can suddenly change their direction of travel or suddenly slow down or accelerate. Schwarz: "You have to expect this when travelling through exercise areas."

He understands that this is sometimes difficult to assess. He is also a sailor and is based in Eckernförde with his H-boat. His basic advice in such cases is to keep clear and be alert and vigilant. Especially when crossing the fairway. Then it is important to clearly show what you intend to do. Mutual consideration is important, says Schwarz.

How to recognise marine exercises

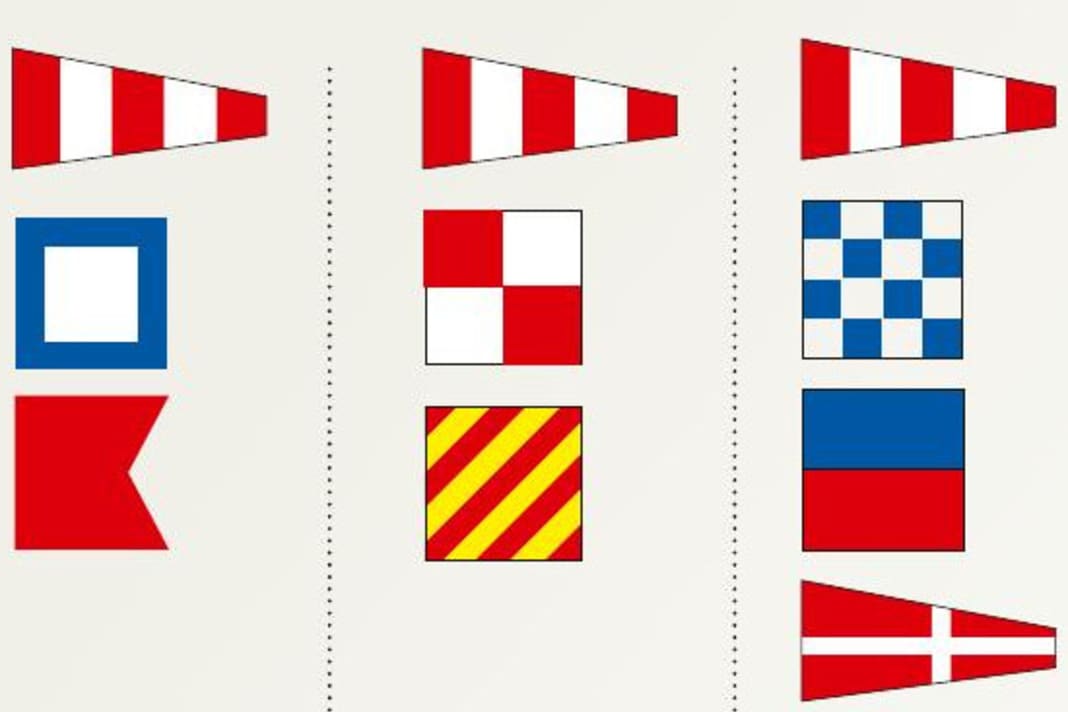

Flags of the international alphabet, which naval vessels hoist during exercises, can also provide information. They signal when you should keep away or when this is absolutely necessary. DSV department head Tatenhorst also recommends consistently monitoring channel 16. If things get tight, navy crews contact the sailors by radio.

The situation is more strictly regulated in the shooting and restricted areas - for example off Putlos or Schönhagen. Recreational boats are not allowed to use these areas when practising. Yellow barrage buoys and security vehicles keep the area clear. Information about shooting times is also provided by radio and online.

Nevertheless, there are times when sailors enter the areas illegally. Some are driven by curiosity, others by ignorance, says Schwarz. "If a sailor enters the area, we stop shooting." So nobody has to fear being shot at. But it can be expensive, because you could be fined.

You should be aware of these signals:

These major manoeuvres are planned for 2025

And even away from the training areas, the grey ships are likely to catch the eye of one or two sailors this summer. Major manoeuvres are planned off the German Baltic coast again in 2025.

- One of these is the annual NATO exercise Baltic Operations (BALT-OPS). Around 30 international warships and even a US aircraft carrier are expected in Warnemünde harbour. In addition to military cooperation, the focus is on defence against drones. The manoeuvre starts on 5 June in Rostock and ends on 20 June with a joint entry at the Kieler Woche.

- Another extensive series of exercises with international participation takes place from August to September with the so-called Quadriga which will involve soldiers from the navy, air force and army. It includes several training sessions at various locations in Europe.

- One is the "Roll to Sea" exercise (18 to 29 August), in which a mass emergency at sea is simulated off the coast of Rostock.

- Another sub-exercise is called Northern Coast. Among other things, the rapid deployment of troops to the NATO flank is being rehearsed. From 29 August one of the locations is Rostock harbour.

In addition to these major actions, there will be various smaller exercises along the German coasts. The Baltic Sea has become a central theatre of geopolitical developments. For us sailors, however, the direct effects are minor and vigilance and consideration are part of good seamanship anyway. Anyone who is forced to change their course or even their sailing plans because of a military exercise should show understanding.