North Atlantic and Iceland: A different kind of Atlantic tour - from the sun to the ice

Fabian Boerger

· 11.12.2024

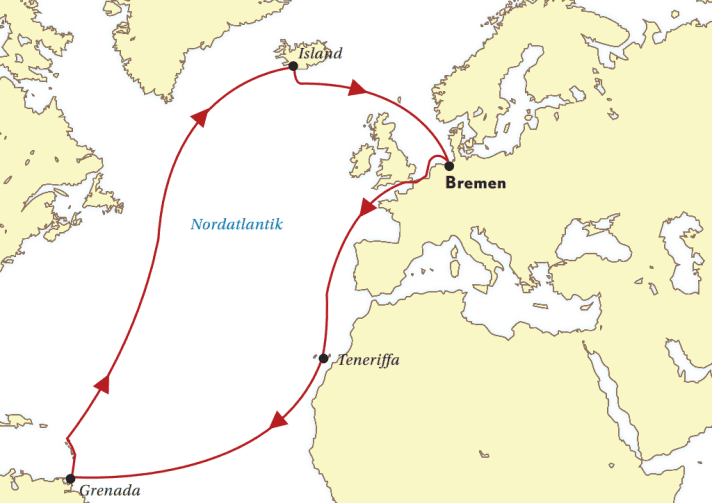

When you think of sailing the Atlantic, Caribbean islands, beaches and palm trees spring to mind. It's like a promise that draws thousands of sailors from Europe across the Atlantic every year. The trade winds are both a reliable helper and a driving force - on the way there and back. It is therefore surprising when a sailor leaves the beaten track, as Marcus Bulgrin from Jesteburg did. He sailed single-handed to the Caribbean; on the way back, however, he chose the challenging route across the North Atlantic - including a stopover in Iceland.

A special kind of Atlantic tour

Marcus Bulgrin started his Atlantic tour in Bremen in August 2022. He first travelled via the Netherlands and Belgium to Plymouth in England. Due to the orca activity in the Bay of Biscay, Bulgrin decided to sail directly to Tenerife. It took him 14 days to make the crossing to the Canary Island, where he spent two months.

On 24 November, Bulgrin set off from there to cross the Atlantic and reached Grenada 25 days later. For four months, he explored the islands of the Eastern Caribbean, sometimes with his partner. At the end of April 2023, he set sail from the Virgin Islands to Iceland. The crossing took 43 days. After a 14-day break in Iceland, he sailed straight back to Bremen, where he arrived in August 2023.

About dreams and doubts: Marcus Bulgrin in a YACHT interview

Mr Bulgrin, you sailed from the sun into the ice. Why all the hardship?

I wanted to experience the extremes. After four months of sun in the Caribbean, I wanted to sail into the ice - so first the heat, then the cold. The idea behind the trip was to experience both extremes and to sail a long distance again non-stop and single-handed.

Iceland was not yet planned as a stopover when you set off.

Well, not quite. It was planned, but only on the condition that the North Atlantic would let me. When I set off from the Caribbean at the end of April, there were still a lot of low-pressure systems and storms in the region. But the further north I sailed, the fewer they became, so I was able to hold my course. The weather finally co-operated.

Storms and cold are not exactly inviting. What attracted you to this route?

Well, there are now many books and videos about the classic route - following the winds via the Azores. But the return via Iceland? I've hardly found anything about that. So I thought I'd try a different, more challenging route.

By planning the route, you deliberately exposed yourself to several different challenges. What did these consist of?

When sailing in the Caribbean, you follow the sun. The further west you go, the warmer it gets. At some point you can literally smell the Caribbean. Every day was exciting because I got closer and closer to my destination. The return journey via the far north was different. For one thing, it marked the end of my journey. For another, the weather became more unsettled and the sailing more challenging.

It took you 43 days to travel from the Virgin Islands to Iceland. That's a long time under these conditions. What does that do to you?

It was definitely a challenge and not exactly conducive to motivation. Sometimes I had really hard times, especially at night when it was dark. I knew that the next person was over 500 nautical miles away and further. Compared to the outward journey, where you always had the trade winds at your back, the return journey was mostly against the wind. Then there are the horse latitudes, where there is either no wind or it comes from all directions - just not from the desired direction.

How did you deal with this in practice on board?

I tried to hang on to the weather systems so that they took me in the desired direction. Sometimes I first had to sail in a completely different direction in order to hit them optimally.

Did you have any moments of doubt during your journey?

Yes, of course there were.

Can you give us an example?

I well remember a situation where I had already been at sea for two or three weeks. I was far out, north-east of Bermuda. The wind was coming from the north-east, exactly the direction I wanted to go. I was sailing high on the wind. It was at night and the waves were relatively high - about five to six metres. Not so high that it would have been critical for the boat, but the bow kept digging into the waves.

It felt frightening when the waves broke over the boat and ran into the cockpit. It creaked everywhere. It felt very powerful and mighty to me. It made me feel very small and lonely. Even if I had decided to give up, it would have taken me more than a week to reach the North American mainland. For someone like me, who normally sails on the Baltic Sea or the Elbe, that was quite a challenge.

Situations like this stay in your memory. What have you learnt from them?

Nowadays it's easy: you get on a plane and fly all-inclusive to the Caribbean or Iceland. For me, however, it was the challenge that made it special and made the destination so worthwhile. Achieving your goals under your own steam and despite adverse circumstances creates different experiences and leaves lasting impressions; that's what I took away with me.

You said that you had no ocean experience: Was that an obstacle?

In 2019, I sailed via Norway to the Shetland Islands; this trip lasted four days and covered around 450 nautical miles; from there I sailed back in one piece; this was the first test of whether I felt comfortable sailing longer distances alone; however, you can't really call this experience I only really gained this when I sailed from Plymouth to the Canary Islands This lasted 14 days and led across the Bay of Biscay This tested both the performance of the boat and my own endurance at sea It was only through this trip that it became clear that I can endure longer periods at sea

You reached Iceland in June 2023. What happened next?

I stayed there for 14 days and explored the country and its inhabitants. It was a great experience. On the way back, I actually wanted to stop in the Faroe Islands. But when I learnt that pilot whales are slaughtered there every year, I decided to avoid the islands - and drove straight through to Bremen.

"Achieving your goals under your own steam and despite adverse circumstances creates different experiences and leaves lasting impressions."

When you look back on this trip now: Was the way to the Caribbean easier than the passage to Iceland?

Crossing the Atlantic from east to west is easier. Once you have found the trade wind, it pushes the boat across the Atlantic with constant strength and direction. In the hurricane-free period, storms are extremely rare. So I had a pleasant crossing. The passage to Iceland goes through the windless horse latitudes, the erratic latitudes of the variable winds and the many low-pressure areas in the North Atlantic. I had to learn how to use the weather systems to my advantage. Looking back, I worried too much before starting the trip. You learn a lot while you're doing it - but you only realise that in hindsight.

So the biggest difficulty was not at sea?

No, looking back, the hardest part was letting go of the ropes in the first place. I thought about it for a long time beforehand: how would it affect me professionally? There were always reasons not to do it. Today I wish I had done it earlier.

How did you finally manage to arrange it?

I have taken a sabbatical year. Since the start of my trip, I have received 75 per cent of my salary, which is regarded as an advance that I am now paying back. For the next three years, I'll be working full-time but only receiving 75 per cent of my salary. As a result, I didn't have to save much beforehand. My employer has been very supportive.

So you were finally able to start your Atlantic crossing. What impressions did the outward journey leave you with?

There were already some impressive moments during the crossing in the summer of 2022. At night in the Bay of Biscay, I saw lights lined up in such a way that they looked like an aeroplane runway. At first I couldn't place them, but they must have been fishermen fishing with longlines. This was really unusual as there was no AIS signal from them. Another impressive moment occurred between the Canary Islands and Grenada.

It was a balmy night. The trade wind drove the boat swiftly through the water and the water - or rather the plankton - around me was fluorescent. At the same time, the sky was full of stars and the water was shining. The two merged seamlessly. It was a sublime and exhilarating moment, as if the boat was flying through space. This image burned itself into my memory.

And when you arrived in the Caribbean, how was it there?

It was almost a little kitschy. The beach, the palm trees and the sun were reminiscent of picture book scenes. They were postcard motifs that triggered feelings of happiness. My dream had been to sail to the Caribbean under my own steam. When that finally became a reality, I felt almost ashamed because it was so beautiful.

Many dream of it. But there are also concerns: too expensive, too crowded. What was your experience?

I was aware of that. But I can say that my expectations were exceeded. I found secluded bays where I was alone for days on end. The water was as blue as in the sailing hero books of my childhood. Yes, there are full bays. But I didn't necessarily find that negative. It was also wonderful to socialise with others. What's more, you always met crews sailing in the same direction. To summarise, my expectations were exceeded.

Your boat, a Hallberg-Rassy Monsun 31, was also unusual. 30 years ago it was considered large; today it's more of a small boat. Why this boat?

They say that you don't find the boat, the boat finds you. I really appreciate classic lines and am a great advocate of long keels. With their V-shaped hulls, they glide smoothly through the waves. I trust this traditional design. Of course, they are difficult to manoeuvre in narrow harbours and going backwards is almost impossible.

But it was the first boat I viewed and I was immediately impressed. As I said, the boat found me. Another reason was that ten years ago, a Monsoon crossed the Northwest Passage when I was looking for a boat. That impressed me. I thought to myself: if this boat can do it, then it will take me anywhere.

What preparations did you make for the trip before you set off?

Even before the trip, I wanted to sail alone, for which a wind steering system is essential. I'm a big fan of this technique. I didn't touch the tiller once during the entire Atlantic crossing. I set the wind vane, corrected it occasionally and only took over again at the finish. Another point was the choice of sails. On the Baltic Sea, one set might be enough, but for the Atlantic I had more choice - smaller headsails, a new main and a third reef. I also renewed the standing and running rigging.

With an iPad, GPS and other devices, the power supply on board is very important. I therefore installed solar panels, which worked well, although space was limited. I also opted for a wind generator. I also worked intensively on energy management so that I could be at sea for a month and a half without having to use charging current. This proved to be sensible, even though my overall power consumption was rather low.

You've been back for over a year. What happens next?

Firstly, I have to catch up on my sabbatical year and there are also a lot of things in my private life that need to be dealt with. But my desire to sail remains unbroken. I would say that my dreams have even expanded as a result of the trip. I have gained more confidence and trust than before. The longing for sailing, the freedom and the feeling I had when I sailed through what I thought was outer space on the Monsun will never be forgotten.

Are these dreams in warm or cold regions - in the sun or in the ice?

Both. The longing and the dream is to sail around the world. It could also be a classic route that includes both equatorial, warm areas and cooler, windier regions. And I don't want to wait until I'm 65 to do that.

Would the Monsun be the preferred boat again?

It would have its appeal. I'm sure she would be able to do it, as other sailors have already proven.

The Hallberg-Rassy Monsun 31 in detail: particularly seaworthy with solid substance

The Monsun was not only the first model from the Hallberg-Rassy shipyard founded by Christoph Rassy in Ellös on Orust, Sweden, in 1972, but is also the most successful to date. The GRP classic is known for its longevity and is therefore still a very popular second-hand boat. The Monsun has already successfully completed several round-the-world voyages.

Technical data Hallberg-Rassy Monsun 31

- Designer: Olle Enderlein

- Overall length (hull length): 9,36 m

- Waterline length: 7,50 m

- Width: 2,87 m

- Depth: 1,40 m

- Weight: 4,2 t

- sail area: 39 square metres

- Built from 1974-1982

- Quantity: 904

- Average used price: 32.500 €

More contributions to Monsoon 31: