Active for the oceans: These projects are available for marine conservation

Andreas Fritsch

· 25.12.2023

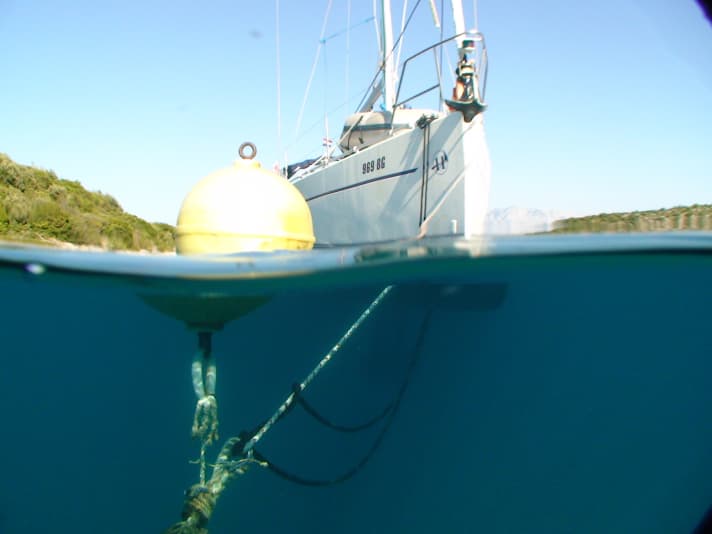

- Marine conservation project 1: Buoys instead of anchors

- Marine conservation project 2: Planting of seagrass meadows

- Marine conservation project 3: Anchor bays under control

- Marine conservation project 4: k Artificial reefs

- Marine conservation project 5: Recovery of ghost nets

- Marine conservation project 6: Avoiding microplastics

- Marine conservation project 7: i nternational Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment

Research has been pointing out the huge problems facing the oceans for decades. Even some scientists are now of the opinion that their causes have been sufficiently investigated. What is lacking, however, is decisive action to finally eliminate them. This starts with the dramatic overfishing of almost all oceans because the fishing fleets are still far too large and the fishing quotas are not low enough. It continues with the nutrient input from agriculture, for example in the Baltic Sea region, which politicians are failing to stop. And it ends with the destruction of habitats for marine fauna and flora, which is still largely ignored. Researchers have long been pointing out possible solutions, with recommendations to politicians. But they are acting too slowly or timidly. On the one hand, because bans rarely win elections. But also because overpowering lobby organisations, such as those in agriculture or fisheries, know how to effectively defend their interests in Berlin and Brussels.

Nevertheless, there are approaches that are encouraging, such as the recent UN resolution to protect the high seas. But it remains to be seen whether this will be followed by action. Many people no longer want to wait for "those at the top" to do more than draw up declarations of intent. They are taking action themselves. And clean up. Collecting rubbish. Planting seagrass meadows. Building artificial reefs. Collecting ghost nets from the sea. Below we present a few of them and their projects.

Marine conservation project 1: Buoys instead of anchors

To protect the seabed from yachts anchoring, more and more buoy fields have been created over the past decades. Free anchoring, especially in biologically valuable areas, is then only permitted to a limited extent or not at all. Such fields have already been created around some of the Balearic Islands, for example, as well as on the coast of Corsica and Sardinia and in large numbers in Croatia and the Caribbean. The sometimes high costs of using the buoys are controversial. In Croatia, it is not uncommon for around two to four euros to be charged per metre of boat, often without any additional services in return, such as the removal of waste produced on board.

There are also the first buoy fields on the Baltic Sea, albeit in very small numbers. The Swedish Cruising Club has laid out 240 buoys in popular locations, but now urgently needs government funding to increase this commitment. The Dansk Sejlunion has also been operating a few buoy fields for years. However, so far only club members have been allowed to moor. And in Sweden, the Värmdö region, for example, wants to ban anchoring in shallow bays in future and only allow mooring buoys. However, such measures are not uncontroversial. However, they are based on clear findings.

From 2019 to 2021, the East Swedish Archipelago Foundation and WWF investigated the impact of buoy fields in the Stockholm region. The result: in bays with buoys, there was a six to seven times higher population of ecologically sensitive and valuable plant and animal species at the bottom than in those without a ban on anchoring. The small protected island of Cabrera off the coast of Majorca and some stretches of coastline in Sardinia have also seen a significantly greater abundance of species since buoy fields were installed there.

Marine conservation project 2: Planting of seagrass meadows

Projects aimed at protecting seagrass beds are still relatively new, especially in the Baltic Sea. Some of the plants are even to be re-established on sandy soils that have become increasingly deserted in recent years. A research project led by Professor Mathias Paschen from Rostock is dedicated to this endeavour and is supported by the Climate and Environmental Protection Foundation of the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Paschen is developing special substrate mats that hold seagrass seedlings and are then laid out on the seabed.

"We have tested various mat systems at two locations. In each case, a decomposable carrier material is used, such as hemp, flax or old seaweed," explains Paschen. In this way, it is possible to spread the sensitive young plants over a large area and provide them with support until their roots are strong enough to withstand currents and waves on their own. The carrier material simply decomposes later. Paschen: "Ideally, the whole process takes place in water depths of around seven metres. Water that is too shallow becomes too warm in summer, which the plants cannot tolerate. They are also exposed to stronger wave movements there." But it shouldn't be too deep either, as the plants need enough light to grow.

The team around the engineer has already gained a lot of experience. The seedlings on the carrier mats require good conditions for around four to five months in order to grow. After that, they are relatively robust.

However, it is not only the wind and currents that are causing problems for the Rostockers in their planting endeavours, but also the authorities on land. "The water and nature conservation authorities must categorise the seagrass planting as an improvement to the status quo of the water. That hasn't happened yet. But only when that happens could a boom begin," says Paschen. Because: "Many companies, such as wind farm or cable route operators, have to take compensatory measures for their construction projects in the North Sea and Baltic Sea. Or at least make compensation payments. They would naturally like to support initiatives such as our seagrass planting programme. But they need the official blessing first."

Another difficulty is obtaining sufficient seedlings for the mass production of the planting mats. Until now, the cuttings required for this have mostly been taken from existing meadows in the sea. However, this cannot be the solution and must be done by other means in future.

Incidentally, over a hundred years ago there were far more seagrass meadows in the Baltic Sea than there are today. Back then, the water was not yet so heavily polluted with nutrients and algae. The plants thrived at depths of up to 17 metres. Nowadays, they only get enough sunlight down to a maximum depth of ten metres.

Marine conservation project 3: Anchor bays under control

Unfortunately, water sports also contribute to the destruction of marine habitats. One example of this is the damage caused by hundreds of thousands of anchor manoeuvres in the biologically valuable seagrass meadows. A single chain swinging along the bottom can tear huge scars dozens of metres long into the sensitive grass fields. But these are nurseries for many species of fish, crabs and other marine animals. Anchoring in seagrass has long been prohibited under EU law, but this happens again and again in the Mediterranean.

The authorities on the Balearic Islands, for example, are trying to change this. A fleet of 18 inspection boats now regularly visits popular anchorages in the archipelago and checks whether crews have dropped their anchor and chain in a seaweed meadow. In 2023, a total of 180,000 such checks were carried out and offences were punished in 7,578 cases. The yachts in question had to be moved immediately and the skippers were fined in some cases. When the campaign took place for the first time, the proportion of offences in the total number of checks was around ten percent; one year later it was only five percent. The measure for marine protection therefore appears to be working.

Marine conservation project 4: kArtificial reefs

Around 20 years ago, the first and to date only artificial reef in the German Baltic Sea was created off Nienhagen to the west of Warnemünde using specially moulded concrete elements. With success: whether fish, mussels or crabs - populations on the reef were three to four times larger than in neighbouring areas with only bare sandy bottoms. The researchers' recommendation at the time was clear: establish several such reefs along the coast. However, nothing has happened since then. "This is mainly due to legislation. According to water and environmental law, reef structures represent an interference with nature that must be avoided. Only if such an intervention improves the environmental situation can it be authorised. And many authorities don't go along with this," explains Dr Peter Menzl from the Fraunhofer Institute and the Ocean Technology Campus Rostock, who are now in charge of the reef. In the authorities, you often meet conservationists who are opposed to any human intervention. Nature should rather be left to its own devices.

A Danish study comes to the conclusion that around 55 square kilometres of reefs in the Baltic Sea have disappeared in recent decades precisely as a result of human influence. However, no new reefs form on their own. In the neighbouring country, a whole series of artificial reefs have therefore been built in recent years, for example at Samsø, Anholt and Greena. The WWF, the city of Greena and the Kattegat Centre recently anchored ten "Biohuts", termite-like concrete structures, to the bottom of the Baltic Sea in 2021. As many as 100 of these structures were installed when the harbour in Copenhagen was redesigned.

Jonas C. Svendson, who is in charge of many of the projects, says: "We have created around 20 reefs in Denmark so far, and biodiversity is increasing everywhere." He is also aware of the legal hurdles. "Only if we build the reefs out of natural stone do we have a chance of getting it through as an 'improvement to the environmental situation'. But that's time-consuming and expensive because the stones have to be transported from far away," says Svendson. "On the contrary, we are currently experimenting with special concrete surfaces that are to be used in the construction of foundations and supporting pillars for harbour facilities, bridges or wind turbines." The surfaces are rough and have holes and protrusions so that they are quickly colonised, for example by mussels and plants. Svendson: "Mussels filter the water. That also helps to improve the water." However, as long as the nutrient input from agriculture into the Baltic Sea is not reduced, all other protective measures will only have limited success.

Marine conservation project 5: Recovery of ghost nets

The problem of ghost nets came to public attention around ten years ago. A significant number of salvage operations have been carried out for around six years. Time and again, professional fishermen lose nets, some of them huge, which are then simply left lying on the seabed, where they cover previously intact ecosystems in some places and virtually suffocate all life - or at least seriously disrupt it. Parts of the nets are also ground up on the seabed due to the constant movement of waves or currents. They end up as microplastics in the water and on our plates via the food chain.

The WWF and the Society for the Rescue of Dolphins (GRD) are very active in recovering ghost nets off the German coast and in the Mediterranean. According to the animal welfare organisation, they make up around 30 to 50 percent of the plastic waste in the world's oceans. Whether trawls, gillnets or fish traps - if they break free or are abandoned or even illegally disposed of in the sea because they are damaged, they become a deadly threat to fish, whales, seals and turtles. Seabirds also become entangled in the mesh and then perish miserably. A study has revealed that around 344 different species have been found dead in ghost nets to date.

The conservationists regularly initiate salvage operations. On the Baltic Sea, for example, they sometimes retrieve around ten tonnes of old nets from the water. They are tracked down with the help of towed sonar devices. If a ghost net is suspected, the next step is to deploy divers. They then carry out the actual recovery.

French environmental groups have discovered how important it is to remove the nets. Where dead patches had formed on the seabed, flora and fauna had re-established themselves just one to two years after the nets were recovered.

Marine conservation project 6: Avoiding microplastics

In the past, the pace of politics and governments has sometimes been agonisingly slow when it comes to implementing concrete environmental protection measures. However, there has at least been some movement recently. For example, the EU has banned certain single-use plastic products that too often simply end up in nature. These include drinking straws, party cutlery and, above all, plastic bags.

Now even the UN wants to follow suit. In 2022, the global alliance of states decided that a binding roadmap for reducing plastic waste must be on the table by the end of 2024. The intention behind this is to promote a functioning, global circular economy and ban ecologically harmful materials from production altogether.

It will be interesting to see whether this noble endeavour will actually succeed by the end of next year and what the outcome will be.

Marine conservation project 7: international Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment

After 15 years of tough negotiations, the UN agreed on a marine conservation agreement for the high seas in 2023. It applies to all areas 200 nautical miles or more from the nearest land. The declared aim is to place 30 per cent of these gigantic areas under protection. So far, only one per cent has already been protected. The agreement stipulates that economic projects and expeditions in the protected areas must undergo an environmental impact assessment and be officially authorised. At the same time, 20 billion US dollars have been made available to support marine conservation projects, which can now be utilised.

The catch is that the agreement still has to be ratified and transposed into national law in 60 member states. Only then will it enter into force worldwide. At least such UN resolutions no longer need to be unanimous, as China and Russia in particular had demanded. A three-quarters majority will suffice in future.

Further topics in the sustainability special:

- 25 tips to help you sail more environmentally friendly

- Sailing yacht vs. motorboat: which model is more sustainable?

- Boatbuilding ecolution: These shipyards are working on sustainable concepts

- Shipyard portrait Greenboats: Boats made of flax and components for Boris Herrmann

- Sustainable fashion: oilskins and other functional clothing - the best products

- Sail recycling: not just stylish bags - what happens to old cloth

- Boat recycling: the never-ending story of GRP

- "Losing is not an option" - Boris Herrmann on sustainability in motorsport

- Sustainable management: Wooden boats in charter operations

- Equipment: Every sailor should reach for these green alternatives

- Drinking water on board: you can filter water correctly using these methods

- Baltic Sea: How does a harbour become sustainable?

- Research yachts: Climate protectors under sail

- Pallets, bottles, flip-flops: creative recycling ideas in boatbuilding

- Monsoon 31: Greenfit instead of refit, what does that mean for the 50-year-old Hallberg-Rassy?

- "Nomade des Mers": a catamaran as a low-tech laboratory

- Self-build yacht "Ya": Totally self-sufficient on a trip around the world

- Sustainable boat project: 55-foot catamaran made from recycled aluminium

- The Schwörer family and the "Pachamama": On a long voyage for climate protection

- Nike Steiger on her recycling project