Those were wild times: the world's oceans in the sixties were virtually untouched as far as yachting was concerned, and long-distance sailors were a rare, exotic species. Those were the days of the pioneers who first demonstrated what was possible on the water, such as a single-handed circumnavigation without stopping, which Robin Knox-Johnston was the first to achieve. Ocean sailing was still very unfamiliar territory.

But soon after Knox-Johnston's return in 1969, regatta organiser Guy Pearce and ocean sailor and publicist Anthony Churchill joined forces with one goal in mind. They published a brochure promoting a team race around the world in the sternwaters of the old square-riggers that had travelled the world on their trade routes.

Looking for sponsors even back then

Several skippers immediately announced their interest in organising such a race. At first, there was no yacht club to organise the event, let alone a financier. Sailing had produced many tragedies and potential supporters were reluctant to get involved.

The Navy, however, was in the process of acquiring several 55-foot ocean-going yachts to train its soldiers at sea. They liked the idea of a team race around the world so much that they couldn't wait to see if Pearce and his team reached their goal. It was agreed that if Pearce's people were unsuccessful in their search for support by the end of April 1972, the Royal Naval Sailing Association (RNSA) would organise the race itself.

Pearce and Churchill soon deviated from their chosen course. They agreed with the Financial Times to organise a race around the world, with a stopover in Sydney. This race actually took place years after the first Whitbread Round the World Race, but only attracted four teams and was doomed to failure.

In the meantime, RNSA club secretary Pat Godber pushed ahead with the plans. He was also the one who achieved the breakthrough with his contact to the traditional British brewery Whitbread & Company after a tenacious and ultimately unsuccessful search for sponsors.

The Whitbread Round the World Race

Whitbread supported the project financially and logistically. The Navy made its base in Portsmouth available as a pre-start assembly point and played the leading role anyway with its worldwide contacts, members skilled in organising major events and outstanding communication capabilities.

Whitbread's title sponsorship was possible even though the sailing rules of the time prohibited advertising. The yachts were exceptionally allowed to be named after a sponsor. This concession was due to the fact that the RNSA boats were called "Adventure" and "British Soldier". In the interests of fairness, such an opportunity for image advertising should be open to all teams. It was used by "CSeRB" (Italian furniture), "Burton Cutter" (British tailoring chain), "33 Export" (French beer), "Kriter" (French wine) and "Great Britain II" (advertising a 19th century steamship and a tourist attraction at the time).

On 8 September 1973, a pistol shot opened the Whitbread saga in the spirit of the times: a colourful array of series ships set off, with amateurs, adventurers and students on board. The name characterised the dazzling history of the race around the globe for a quarter of a century. However, the seventh and last race under the old name had already made its mark with the new strong sponsor Volvo: the 1997/98 regatta was officially called the Whitbread Round the World Race for the Volvo Trophy. It marked the transition phase.

The Volvo Ocean Race

Since the eighth edition in 2001/02, the Swedish car manufacturer Volvo has managed the race. And it began to consistently develop this advertising tool further. The majority of the extreme Southern Ocean stages were gradually sacrificed in favour of more commercially and medially relevant harbours and areas. The race no longer centred around all three capes, but only two. The course orientated around the clipper routes became a zigzag course through the Atlantic, Indian Ocean and Pacific.

A new boat was introduced for the 2014/15 edition, the Volvo Ocean 65 (VO 65). A strict standardised class, all components came from the same manufacturers and nothing was allowed to be changed. This saved the teams the high costs for their own designers and boat builders and increased the equality of opportunity for more excitement during the stages. The use of these boats was planned for two editions, but a lot happened in the four years leading up to the 2017/18 race. The boats took off in the America's Cup, reaching speeds of up to 50 knots. The hulls were also fitted with foils for the Vendée Globe, where similarly sized Imoca 60s are used.

In contrast, the VO 65s with their tilting keel and normal centreboards seemed almost old-fashioned, although they are by no means tame cruisers. The competition for sponsorship became tougher.

Mark Turner, the main organiser at the time, was forced to take an unusual step. Months before the Volvo Ocean Race 2017/18 even started, he announced the switch to a new type of boat - two new ones in fact. A new, 60-foot-long monohull was to be designed, which would be foiled and could also be used in the Vendée Globe with minor modifications so that future teams could compete in both regatta heavyweights with the same equipment. At the same time, there was to be a new flying catamaran with which the in-port races were to be contested, almost like mini America's Cups. But none of this materialised.

The emergency birth of The Ocean Race

After the 2017/18 race, Volvo withdrew as title sponsor. A new era began for the race, a reorientation. Originally, the race was supposed to be sailed in 2021, but the coronavirus pandemic intervened. At the same time, the second major regatta around the world, the Vendée Globe, sailed single-handed on 60-foot Imoca-class yachts, became increasingly popular and saw a number of new builds. And due to the pandemic, more and more racing teams were struggling to find the budget to take part. The organisers therefore decided to advertise the Ocean Race for two classes, the Volvo Ocean 65 introduced in 2014 and Imocas sailed with a crew. However, only five Imocas and six Volvo Ocean 65s entered, with the latter sailing a shortened course outside of the classification.

Nevertheless, this Ocean Race was and is the most famous team regatta around the world. The racing action is gripping, the episodes are incredible and sometimes tragic, and the protagonists who have battled the elements in this almost 50-year saga are famous.

Heroes and tragedies

Strong characters with the strength of a bear gave the Ocean Race a face. Such as the "Flying Dutchman" Cornelis van Rietschoten with two consecutive victories on "Flyer" and "Flyer II" as an early pioneer of professionalisation. Such as Sir Peter Blake, who was murdered by pirates during an expedition in South America in 2001 and also dominated the America's Cup. On his fifth attempt in 1989/1990, he won every single stage on "Steinlager II". No skipper before or since has achieved this. "It was time we conquered Everest," said Blake. He never took part in the Ocean Race again.

Eight times: Bouwe Bekking

The dream of triumph has also fuelled record participant Bouwe Bekking - in eight starts in more than three and a half decades. However, the Dutchman has never been able to win the race of his life - just like Ivan Lendl once won Wimbledon. Most recently in 2018, Bekking and "Brunel" were 23 minutes and 20 seconds short of victory in the most exciting final in Ocean Race history. This was secured by Charles Caudrelier's "Dongfeng" team. At the finish in front of his home crowd, Bekking had to watch as his compatriot Carolijn Brouwer, as part of Caudrelier's crew, was honoured like a queen in the finish harbour of Scheveningen. "That was the most important race of my career," she said. "It was a dream come true for me."

The impressive final act on 26 June 2018 also showed in a touching way how closely triumph and tragedy lie side by side. In the shadow of the winners, "Scallywag" skipper David Witt quietly reflected on his crew's tour de force. "I'm incredibly proud of my team, we had a lot to overcome. But I'm also very sad because I didn't finish the race with my best friend John Fisher, who I started with."

The Ocean Race claimed six lives

Fisher went overboard in a severe storm in the Southern Ocean around 1,400 nautical miles west of Cape Horn on 26 March 2018. Despite an intensive search in tough conditions, his team was unable to find him. The 47-year-old Briton remained missing.

It was the sixth fatality that the race has claimed since its inception. Previously, a fisherman was killed in a collision between the Vestas 11th Hour Racing team and a Chinese fishing boat shortly before the finish in Hong Kong in January.

Until then, the Ocean Race had gone twelve years without a loss of life. Now memories were awakened of the sailing community losing 32-year-old Dutchman Hans Horrevoets on the night of 18 May 2006. The cheerful young entrepreneur had gone overboard from "ABN Amro Two" 1,300 nautical miles west of Land's End. He left behind his pregnant wife Petra, their eleven-month-old daughter Bobbi and badly injured crew mates, who rescued him but were unable to revive him despite attempts at resuscitation.

Just two days after this tragedy, it was the young sailors on "ABN Amro Two" who became rescuers with their dead crew mate on board. As the closest boat, they rushed to the aid of a sinking ship: Bouwe Bekking's "Movistar", which had to be abandoned after the keel suspension broke. The disabled men found shelter with the men with the heavy hearts.

Since the tenth edition, the best youngster in each race has been awarded the Hans Horrevoets Trophy. Michi Müller from Kiel received it at his Ocean Race premiere in 2008/2009.

All winners of the Ocean Race

Year, boat class, winning yacht, skipper

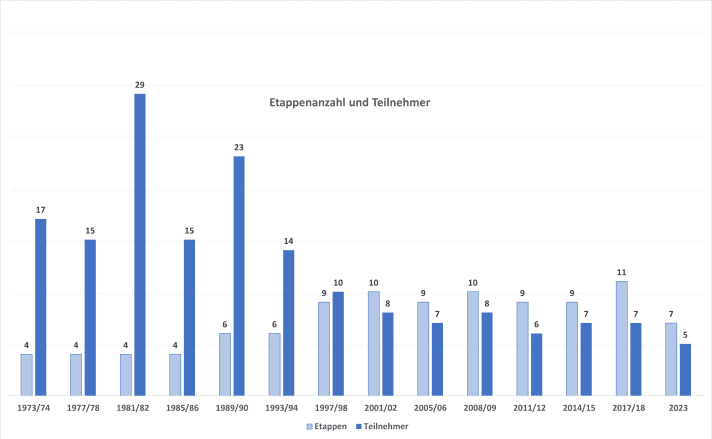

- 1973/74, various yachts, 32-80 feet, "Sayula II" (Mexico), Ramón Carlin (Mexico)

- 1977/78various yachts, 51-77 feet, "Flyer" (Netherlands), Cornelis van Rietschoten (Netherlands)

- 1981/82, various yachts, 43-80 feet, "Flyer II" (Netherlands), Cornelis van Rietschoten (Netherlands)

- 1985/86, various yachts, 49-83 feet, "L'Esprit d'Equipe" (France), Lionel Péan (France)

- 1989/90, various yachts, 51-84 feet, "Steinlager 2" (New Zealand), Peter Blake (New Zealand)

- 1993/94Maxi (85 feet) and Whitbread 60, "NZ Endeavour" (New Zealand), Grant Dalton (New Zealand)

- 1997/98, Whitbread 60, "EF Language" (Sweden), Paul Cayard (USA)

- 2001/02Whitbread 60, "Illbruck Challenge" (Germany), John Kostecki (USA)

- 2005/06Volvo Open 70, "ABN Amro I" (Netherlands), Mike Sanderson (New Zealand)

- 2008/09Volvo Open 70, "Ericsson 4" (Sweden), Torben Grael (Brazil)

- 2011/12Volvo Open 70, "Groupama 4" (France), Franck Cammas (France)

- 2014/15Volvo Ocean 65 (One Design), "Azzam" (Abu Dhabi), Ian Walker (Great Britain)

- 2017/18Volvo Ocean 65 (One Design), "Dongfeng Race Team" (China), Charles Caudrelier (France)

- 2023 Imoca/Volvo Ocean 65