The news hits like a bombshell: Dutch twin brothers Robbert and Rudolf Das are accused of espionage by the British press in 1952. The reason for this was the publication of detailed perspective drawings of the Royal Air Force's new and top-secret fighter jet, the Vickers Supermarine Swift, in an international aviation magazine. The drawings of the turbine and weapons technology are so incredibly precise that nothing other than treason can be assumed.

However, after a brief period of turbulence at government level, the brothers were able to prove that they had worked exclusively with publicly available information. They were able to eradicate unknown details with their high level of technical understanding. Nevertheless, they have to promise "not to do anything like this again".

Warships are painted on wallpaper

The twins were born in Haarlem in 1929. Their father, Henk Das, was a successful furniture and interior designer and recognised his sons' talent for drawing early on. To keep the boys occupied during the dark days of the Second World War, he provided them with rolls of wallpaper on which they could let off steam with their drawings. One sits at one end, the other at the other, and so they work their way to the centre.

The brothers are fascinated by large warships, which they draw with pencils from different perspectives. This gave rise to a passion that would stay with them for the rest of their lives.

After finishing school, the two decide not to follow in their father's footsteps but to start training as pilots. However, due to a slight eye defect on Robbert's part, this idea has to be quickly buried and instead they set up a small agency for technical illustrations.

Espionage affair as the starting signal for a career

The scandal surrounding the British fighter jet and the resulting attention are the starting signal for a great career. Their talent for producing technical 3D drawings with unprecedented precision is suddenly in such demand that they are inundated with enquiries.

But the Das brothers don't just want to fulfil orders. They also designed - even from today's perspective - visionary studies of aeroplanes, ships and entire cities that seemed like science fiction at the time.

Even back in the 1960s, sustainability and clean energy were a major topic for the twins. Their first book "View of the Future" becomes a bestseller and leads to new commissions from companies who want the brothers to illustrate their own vision of the future. Some concepts, such as the residential mounds, which stand freely in the unspoilt landscape and are intended to combine all aspects of living, working, caring and recreation, are actually taken up and realised many years later.

Even on his wedding night, Robbert Das went sailing

While Rudolf continued to specialise in architecture, Robbert became increasingly interested in sailing. He became a passionate regatta sailor and took part in the Fastnet Race several times. Naturally, the design of his "Ros Beiaard" was his own.

"His need to sail became so strong that he even sneaked out of the house at five in the morning on his wedding night to make it in time for the start of a race," says artist Ludo van Well. "But his wife and he had a good marriage, and it stayed that way until her death in 2020. She lived to be 101 years old."

Before that, it was considered impossible to test yachts

In 1965, Robbert Das and his buddy Lex Pranger turn up at the YACHT editorial office in Hamburg and present the programme they have developed with Delft University of Applied Sciences for testing sailing boats.

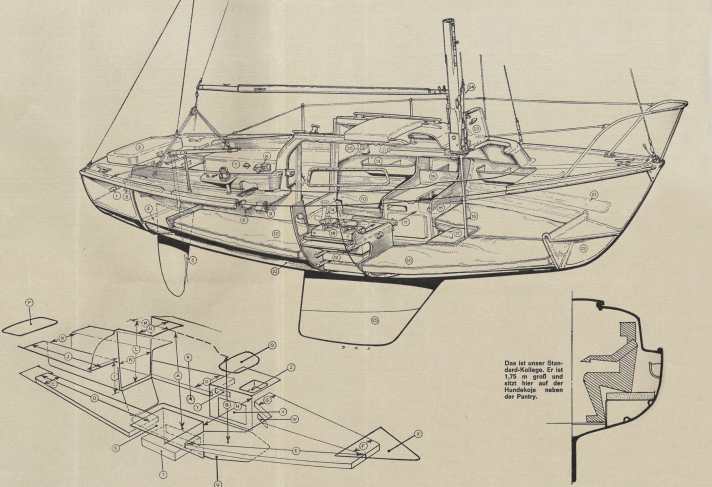

Until then, it was considered impossible to test and compare yachts. While Das presented sketches of test equipment for measuring heel and speed, Pranger tried to score points with his steel-blue suit, yellow tie and an aura of irresistibility. Despite initial scepticism, they won over the editor-in-chief at the time, and the very first YACHT test in the magazine's history took place that same year. On the IJsselmeer, a Victoire 22 is put through its paces with wondrous-looking instruments such as an electronic towing log, heeling angle meter and stopwatch. The tests, which are published every two weeks from this point onwards, are crowned with a 3D drawing of the respective boat by Robbert Das.

The new section becomes so popular within a very short space of time that print runs skyrocket. Robbert is on board for many tests to get a feel for the boat and also to make sketches, especially of the narrow spaces that are difficult to photograph.

Accident during the first catamaran test

The later editor-in-chief Harald Schwarzlose remembers: "Robbert was a special colleague who was not only a treasure for us because of his talent, but also because of his humour!" With tears of laughter, he recounts an episode that took place after a test in Schilksee: "Our crew spontaneously decided to visit an establishment in Kiel where, in addition to striptease and cold drinks, there was also good food. We wanted to let it rip! Robbert was very taken with the ladies and suddenly disappeared. When the stage curtain opened again after a short break to a loud roar, Robbert was standing on it, dressed in nothing but pink pants, doing his capers. The theatre roared with laughter. He was always up for a laugh!"

Things were far more dramatic in the spring of 1968 in Medemblik, the Netherlands, when an English Iroquois cruising catamaran was to be tested. Das, Pranger, Schwarzlose and another editor set sail for the IJsselmeer despite a strong wind warning, even though no one had any significant experience with twin-hulled boats at the time. The boat capsizes far out. The four testers have to leave the flooded cabin and save themselves on one of the floats, which lies just below the surface of the water, while the other one rises into the sky. They cling to the trampoline. In rain, cold and storms, the air chambers of the float prove to be leaky, causing it to sink slowly. The water first rises up to the knees, then to the stomach and up to the chest. "We thought we were going to drown like rats," remembers Schwarzlose.

Suddenly, a sports plane appears, which quickly disappears again, but has apparently requested help. It arrives in the form of a suction dredger, which goes alongside the stricken catamaran and collects the completely hypothermic casualties. With the catamaran in tow, the captain unloads the crew back in Medemblik. Although the boat was a total loss, the test was eventually published and the results contributed to the further development of the catamaran.

This also characterises historic ships

In the 1970s, Robbert emigrated to the south of France and worked like an assembly line. Like a simultaneous chess player, he was able to work on several drawings at the same time, jumping back and forth depending on the flash of inspiration or his mood.

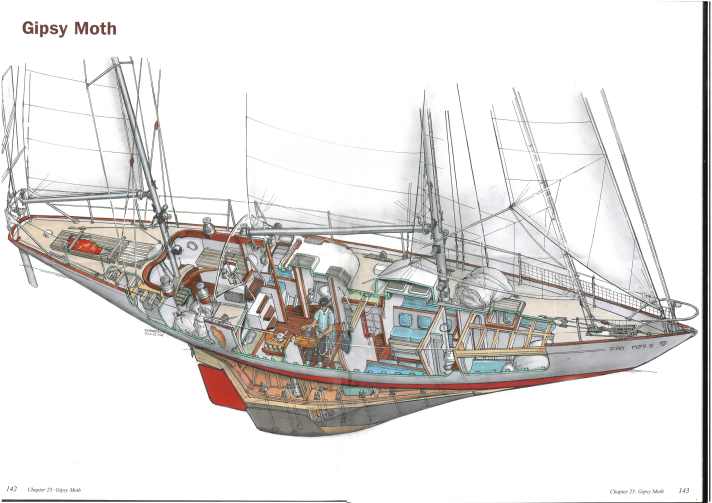

In addition to his commissions for YACHT or the Dutch sailing magazine "Waterkampioen", for which he mainly draws current boats, he is also interested in all historical ships that were technically innovative in their time or with which record-breaking voyages were achieved. Whether Columbus' "Pinta", the J-Class "Endeavour" or the micro-boat "Vera Hugh", with which Tom McNally crossed the Atlantic - Das immortalises them all in his very own style.

His pictures show the ships in a way that no computer programme can - with their soul.

For his 3D views, which always provide an insight into the inner workings of the ships, he uses pencil, ink and watercolours for colouring. His trick for visualising even the smallest details is as simple as it is ingenious: he enlarges them without them catching the viewer's eye. He draws on any paper that seems suitable or is available to him at the time. If there is not enough space on one sheet, he simply sticks on another piece of paper with Sellotape. "His pictures show the ships in a way that no computer programme can - with their soul. And you can also see the dedication with which Robbert has painted them."

Rumours about Volvo Ocean Racer

However, the technophile regatta sailor is also attracted to high-powered racing yachts that plough across the oceans. Even when he was denied access to the Dutch Volvo ocean racer "Black Betty" in 2006, he was not dissuaded and sketched the boat from the pier without further ado. The interior is the product of his imagination and his understanding of the technology and construction of a racing yacht. Like a detective, he locates the exact positions of the rudder, forestays and hull rivets and places everything in context. Once again, the result is astonishingly close to the original, only this time he is not accused of espionage.

However, the rumour persists to this day that the then 77-year-old noticed a cheat with the permissible ballast weight - without ever having been on board.

Visionary ideas find their way into reality

However, Robbert Das also used his artistic excursions into early seafaring to understand technical developments and to venture a glimpse into the future. As early as 1972, he drew a sailing yacht with a canting keel, and ten years later his spectacular designs for foiling racing yachts and rigid wing sails were published.

Initially ridiculed, many years later these ideas would play a key role in the design of today's racing goats and would become indispensable. Once again, the illustrator proves himself to be a visionary.

Despite his penchant for technology and futuristic concepts, he detests the digitalised world. Das doesn't own a computer, a mobile phone or even a calculator.

The free spirit did not waste a thought on pension provision, an omission that would later take bitter revenge. The Frenchman-by-choice never paid into the Dutch pension fund and always relied on his art and the associated fees.

CAD programmes bring Das to the brink of ruin

But then something happened that even he hadn't seen coming: Computer-controlled CAD programs, with which 3D modelling can be produced very cheaply and quickly, replace his drawing skills at a stroke. Robbert Das' fortune begins to melt away and, to his own astonishment, he even outlives his congenial brother Rudolf, who dies at the age of 91.

Today, Robbert Das lives in seclusion in a small town near Nice. His only income comes from the sale of his old paintings and the book "Ocean Pioneers", published by Dokmar, in which he pays homage to the pioneering achievements of great sailors and their boats. In 2018, the Dutch Maritime Museum in Amsterdam decided to safeguard Robbert Das' legacy and recognise his art as a Dutch nautical cultural asset. Dozens of paintings are purchased and shown in a special exhibition in 2024. He will also be accepted as a member of the exclusive association of Dutch marine painters.

At the ripe old age of 90, Robbert Das proves for the supposedly last time that he is still able to imagine himself in other worlds. In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, he travelled back in time and illustrated the "Caudicaria Navis", an 1,800-year-old Roman coastal cargo ship that sailed between Holland and Britain, for an art and reconstruction project in Zeeland.

This lovingly designed picture with warm colours also has something that no CAD program will ever be able to produce: a soul.