Deep in the Midwest of the United States of America, four young men embark on a daring sailing adventure in the autumn of 1898. Inspired by Joshua Slocum, who had completed his round-the-world voyage on the "Spray" a few months earlier, Ken Ransom convinces his friends to circumnavigate the east of the USA in a self-built sailing boat.

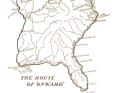

What looks quite feasible on the map and in comparison with Slocum's celebrated solo performance is, however, quite a challenge. From Chicago, the ingenious route leads to the mighty Mississippi, which flows into the Gulf of Mexico at New Orleans. After circumnavigating Florida, the route continues along the US East Coast to New York and the Hudson River before returning to the Great Lakes via the Erie Canal.

That is also interesting:

Today, this loop is known as the "Great Loop" and is mainly used by motorised leisure boats. And for good reason. Around half of the route runs along rivers and canals, which are only suitable for sailing to a limited extent. Boats without a steam engine still had to be towed, either by horse or, in case of doubt, even by manpower.

A ship with an American doer mentality

Ransom and his high school friends are all 18 years old and have to literally beg their parents for permission to go on this long trip. Despite their reservations, they finally get permission. It will be the greatest adventure of their lives.

The required boat is built in a woodshed behind the Ransoms' house. Ransom junior bends the frames and planks from American white oak with the help of a self-built steam chamber. Since leaving school, he has dreamed of becoming a boat builder and naval architect. But how is he supposed to gain the experience needed to construct ships for different purposes and in different conditions?

The answer is very much in line with the American maker mentality: hard work, the courage to take risks and meticulous learning. In Ransom's case, this means building a boat with which he can navigate the rivers and seashores to study the different ships in their respective elements. And his thirst for adventure is also satisfied along the 10,000 kilometre route.

The first test for the boat and its crew is the arduous transport from the shed to the nearest body of water. Over a distance of three quarters of a mile of rough terrain, the young men drag their three-tonne boat over two days using an improvised trailer construction, supported by two horses and a pulley - under the mocking gaze of passers-by. Despite all the prophecies of doom, the gaff-rigged ship is launched and christened the "Gazelle". The 30-foot-long yawl can reduce its draught to three feet by raising the centreboard. The boat has room for four berths, a coal-fuelled galley and plenty of storage space.

First stages of the "Great Loop"

On the morning of 27 October 1898, the anchor is raised and the sails are set. From the shelter of the estuary, the "Gazelle" glides astonishingly well out onto the choppy waters of Lake Michigan. The people on the shore are now just as enthusiastic as the young crew. The St Joseph's lifeboat station fires its congratulations from a cannon, and the new captain Ransom lowers the flag three times in response. On the first night, the excitement is still so great that, despite the changing guards, hardly anyone can sleep a wink.

The first stop is Chicago, where a steam-powered tugboat is organised to pull the "Gazelle" along the Chicago River through the city to the Illinois and Michigan Canal. Having barely arrived on the busy river, the Yawl literally scrapes past disaster: a grain freighter that has run aground suddenly breaks free again and threatens to crush the sailing ship and crew against a quay wall. But fate is kind and allows the freighter to run aground again seconds before the impact, so that "Gazelle" just manages to slip through with barely more than a hand's breadth to spare.

On the Illinois and Michigan Canal, the crew tow the ship 48 miles by hand in two shifts to La Salle on the Illinois River. "We are our own mules," is how crew member Art Morrow describes it. The journey on the river is almost idyllic, apart from a hard collision with the pillar of a drawbridge. But the ship proves to be rock solid, and apart from a broken turnbuckle, it is undamaged.

Harsh winter on the Mississippi

They reach the Mississippi just in time for Thanksgiving Day. Sailing on the legendary river seems to be easy for the Michigan gang, as it appears to be not only wide, but also deep and calm. The direction of flow also fits, so that the "Gazelle" is guided towards the Gulf of Mexico as if by magic. However, after a sudden stopover on a sandbank, they also pay their usual tribute to the "father of waters" and from then on plumb and sound in an exemplary manner.

In the meantime, the newspapers have also got wind of the "Gazelle" and the ambitious plans of her crew, so that the Mississippi steamers salute with whistles of different pitches. The people on deck wave and shout: "Good luck!" and "Have a good trip!"

The onset of winter catches the sailors cold. It will go down in history as the "Great Blizzard of 1899" with record low temperatures. The muffled hammer blows of large ice floes hitting the hull are exhausting and take away many hours of sleep. South of St. Louis, the boys have their worst encounter with the ice. The "Gazelle" is stuck rock-solid in the ice in the middle of the river between two sandbanks. Not only do the supplies run out, but also the coal oil, the only source of heat. Only after eight days is the ship freed and can be towed into a sheltered bay. Here, the hungry crew members shoot rabbits and set off several times on a long march to the nearest town to get more supplies and cash a cheque. Art falls seriously ill due to the freezing cold and is slow to recover.

River with pitfalls

Further downstream, Ken studies the loading of cotton bales onto a paddle steamer. There are always interesting encounters with riverboats, pilots and specialised vessels such as dredgers and log boats. A stroke of luck not only for the inquisitive Ransom, but also for the whole crew, as they learn all about the many pitfalls of the river along the way.

For example, via the Grand Tower Whirlpool, which is considered the ship graveyard of the Mississippi. A sharp bend here creates a whirlpool with a terrifying suction force, while on the other side it quickly becomes shallower and the bottom is covered with sharp-edged rocks and all kinds of debris. Without the help of the local boatmen, the passage would have been impossible or would have meant the end of the "Gazelle".

The four boys have now become experienced sailors who have already survived hard knocks and many dicey situations. Suffering together from hunger, cold and constant fatigue has also strengthened their friendship. The optimistic atmosphere on board is unbreakable and gives even sceptics hope for their success.

In Natchez, the oldest settlement on the Mississippi, where plantation owners live whose wealth is based on former slave labour, the expedition has to survive another ice storm. The spray from the river freezes on the boat to form ice so thick that it threatens to sink. With the courage of desperation, the adventurers chop the ice and shovel it off the boat.

Adventure peppered with youthful recklessness

On 21 February 1899, the "Gazelle" finally reaches New Orleans. To celebrate, the crew treat themselves to a bucket of fresh oysters. But the joy does not last long, as Clyde Morrow receives a message asking him to leave for home immediately. He is urgently needed on his parents' farm. So from now on, with one man less, the Yawl works its way along the Gulf Coast, first eastwards and then southwards. The weather finally warms up and the remaining crew can fish, swim and recharge their batteries to their heart's content.

On the island of Sanibel in southern Florida, which was still farmland in 1899, the crew almost met with their next misfortune. Ken and Frank take the dinghy to the farmer's jetty, follow a path through dense mangroves and make their way to the beach, where they spend a carefree afternoon. After sunset, they search in vain for the way back to the boat and are forced to spend the night on the beach. It turns out to be a scary night: freezing, dehydrated, hungry and surrounded by swarms of mosquitoes, they have to hold out. At dawn, they wash the blood off the mosquitoes and go searching again. They are helped by a dog of all things, which they swear at loudly and throw shells at until it runs off and leads them to its home. His master not only gives them drinking water, but also directions back to the landing stage.

Encounter with the "Pirate of Panther Key"

Further south, on a small island belonging to the Ten Thousand Islands, the group meets the legendary Juan Gomez - better known as the "Pirate of Panther Key". Gomez claimed, among many other things, to have been born in Spain in 1778, which would have made him 121 years old in 1899.

His stories, in which he always interwove himself into historical events, were legendary. Sailors and tarpon anglers visiting the Everglades at the end of the 19th century always stopped off on his island to listen to one or two adventurous stories. For example, Gomez claimed to have served in Napoleon's Imperial Guard or to have sailed and fought with the pirate "Gasparilla". He also told his listeners that the notorious pirate had confided in him on his deathbed where his treasure was buried. He was always prepared to make a treasure map for a fee.

Although most historians agree that neither a "Gasparilla" nor a treasure ever existed, the Gasparilla Pirate Festival is still celebrated in Tampa every year. Without Juan Gomez and his tall tales, Florida would be at least one tourist attraction poorer. Ken Ransom and his crew also benefit from the fascinating old man, who gives them some navigational tips for the Keys.

"Gazelle" proves its worth on the Atlantic

With a mixture of bright anticipation and a good dose of humility, the crew eagerly await their next milestone: entering the Atlantic. Before that, the "Gazelle" has to weather a storm at the tip of Florida for three days. Despite the safe anchorage, the young sailors from Lake Michigan have a sinking feeling in their stomachs. The howling of the wind and the force of the surf waves rolling towards the coral reefs give them an idea of what the ocean, which is still completely unknown to them, is capable of. All fears are dispelled when the sails are finally set again and the crew tackles the first Atlantic section.

The anchor drops again off Miami, the southernmost city on the Florida mainland. At the turn of the century, it still has the character of a village with only a few hundred inhabitants, but is an important transshipment centre for pineapples. After weeks away from civilisation and a diet of coconut and oatmeal, the crew pounces on the juicy tropical fruit and is able to return home.

Despite the temptations, the Yawl sets sail again two days later. The conditions are too good to waste time in the harbour. But as soon as the "Gazelle" glides through Biscayne Bay under full sail, the ship once again runs aground on a sandbank. There is nothing left to do but wait for the next high tide.

Between the open Atlantic and sheltered sailing inland

The three friends want to make the best of the annoyance and go for a swim. After a while, Ken and Arthur are sitting on the dry sandbank, while Frank is still doing his laps in the water some distance away. When he suddenly starts behaving strangely and splashing around wildly, the mates watch him with growing concern. Then the triangular fin of an attacking shark suddenly appears. In his fight for survival, Frank chooses the desperate strategy of counter-attacking and swims with his last ounce of strength and flying arms directly towards the dreaded hunter. Baffled, the shark retreats a little towards the sea. Surprised by his success, the youngster continues to attack until his strength fails him. At that moment, the others pull him out of the water.

With the returning tide, her floating domicile is righted again, and after a few strong pulls on the anchor, she glides into the deep water and onto the open ocean.

Three days later, the entrance to St. Lucie is reached, one of the few harbours on the east coast of the Sunshine State. Behind it lies the well-protected Indian River, which runs parallel to the coast to the north. The only problem is that the waves break dangerously in the narrow entrance. Captain Ransom shows the courage to take the gap, and so the "Gazelle" charges towards the first row of raging breakers like a warhorse ready for battle. Boat and crew prove their seaworthiness and overcome one wave after another until they enter the calm waters of the Indian River.

The sheltered sailing inland is not an unrestricted pleasure. A paradise for fishing, but unfortunately also a playground for blood-sucking mosquitoes. The crew are forced to live in the smoke of burning coconut shells. In desperation, Ransom even builds himself a kind of knight's helmet out of a tin can with holes in it, which he lines with cheesecloth. A grotesque sight, which must have contributed greatly to the amusement.

Local fishermen regularly destroyed the fairway markings to force non-local vessels to use their services. The long-suffering crew of the "Gazelle" nevertheless refrains from doing so and relies on its own, albeit time-consuming, sounding of the water depth. To the north, a small canal connects Mosquito Lagoon with the Indian River. Unfortunately, this channel is currently silted up, which leaves the crew with the decision of either turning back and trying their luck on the outer route or clearing the channel on their own. Since any form of task is alien to them, the hardened hotshots dig their own way out in three days.

Fearless crew on their self-build

At New Smyrna, the "Gazelle" finally sails back into the open Atlantic. Once again she has to pass through a narrow, choppy entrance, the only difference being that this time a shipwreck blocks half of the way.

On their way to Savannah in Georgia, they are caught in a severe thunderstorm that causes the gaff boom to break. In a daring feat, they manage to salvage the mainsail and secure the bobbing boom. What could possibly stop this fearless crew on their self-built boat?

In Charleston, South Carolina, the yacht anchors in the shelter of Fort Sumter, from where the first shot of the Civil War was fired. The next storm is weathered on the Cape Fear River. The ship is stuck for a week off the infamous Frying Pan Shoals, which extend over 20 nautical miles and are responsible for countless shipwrecks.

One night, a rapidly growing shadow emerges from the darkness, which turns out to be a schooner - without a single light. The ships miss each other by just a few centimetres.

Making the "Great Loop" perfect

At Cape Lookout in North Carolina, the "Gazelle" leaves the wild ocean and works its way northwards again, sheltered between the Barrier Islands and the mainland. At Coin Jock, they are taken in tow by a barge loaded with watermelons and guided through a narrow channel to Norfolk. Afterwards, they will again use wind power to travel up the wide Chesapeake Bay and later along the Delaware River past Philadelphia, where countless warships are a reminder of the recently won war against Spain.

Towns with factories whose smoking chimneys bear witness to hard work line the banks of the river every few kilometres, with fields of lush crops in between - not a square metre of land is wasted. A stark contrast to the waterways of the southern United States.

On 7 September, the "Gazelle" sails past the Statue of Liberty. The boys are so excited that they run off course and get stuck on a rock. Once again, they manage to get out of trouble and then manoeuvre their way through a labyrinth of thousands of different ships.

The crew spends a week in the exciting metropolis. They head across the Hudson River to Albany to organise a tow through the Erie Canal. But money is tight and the prices they are asked are far beyond their means. So, without further ado, they buy a horse, harness and feed for ten dollars so that they can tow the 584 kilometres of the canal on their own. When they reach Buffalo after 20 days, Ken sells the black horse for three dollars.

Around 1 November 1899, the "Gazelle" sails into the Clinton River north of Detroit. The following spring, the wake crossed when Ken Ransom brought his boat back to his home town of St Joseph. In a ten metre long boat they built themselves, the boys from Michigan completed an epic round trip that will quite rightly go down in history as the "Great Loop".

"Great Loop" for everyone

Almost any type of vessel is suitable for travelling along the Great Loop, whether sailboats, motor yachts, houseboats or canoes. It is important to know the height and draught requirements of the respective vessel.

The characteristics of the boat largely determine which route can be chosen. Draughts of less than 1.50 metres and heights of less than 4.60 metres allow a free choice of route without restrictions. Vehicles with a draught of over 2.50 metres or a height of over 6 metres cannot complete the journey at all. The limiting point is a fixed bridge in Chicago. For sailboats with a lowered mast, the bridge clearance height should be a maximum of 5.50 metres, ideally only 4.50 metres, in order to be able to complete the large loop.

The masts can then be raised again in the Great Lakes. The marinas there offer this service before and after entering the New York State Canal System. But also in Chicago or Mobile, Alabama. Travel guides also provide information on which harbours offer support.