One of the questions I am asked most often in connection with my 2020 race around the world is: "Don't you feel lonely?" My answer is always the same: there is a difference between being lonely and being alone.

I can't really say whether I'm someone who likes to be alone by nature. I come from a big, noisy family. Three siblings, we are only six years apart. My childhood was filled with voices, hustle and bustle, constant company. And yet I think I'm more of an introvert. I've never felt comfortable being the centre of attention. It makes me nervous to enter a room where I don't know anyone. I try to avoid situations like that. But I love cooking for lots of people and filling my house with life - with laughter, conversation and all the things that make friendship and family come alive. Knowing that I have brought all these people together makes me happy. So did I start single-handed sailing because I wanted to be alone? Or did I only learn to cope with being alone through single-handed sailing? I think the latter is true.

Also interesting:

When I sail across the oceans with my IMOCA, I do it voluntarily - and deliberately alone. Single-handed sailing is the discipline in which I have been trying to do my best for 15 years. Everything is the way I want it to be. If I needed people around me all the time, I would have found another sport. To sail around the world alone, I have to leave my home, my friends, my family and my team behind and get by with just me for three months. When the last team member leaves the boat before the start, I'm always relieved. Sure, there's that tug in the pit of my stomach, the enormous pressure to perform. But I also know that I'm exactly where I want to be. Nobody is stopping me.

I don't feel lonely because I know that all the people I'm leaving behind will remain a part of me. They support and think of me, follow my race, but also lead their own lives. I don't expect to be constantly present for them during my time at sea. But I know that if I need a good word, a quick call, a message, and I'll get an answer. Loneliness is something completely different. You can be surrounded by people - and still feel lost.

Inner strength for single-handed sailing

Perhaps one of the hardest aspects of sailing single-handed for months on end is finding the strength to carry on by yourself, without any contact with others. How often in life do we rely on people to pick us up when we don't know what to do next? A nod of approval, a warm hug, a shout of encouragement - all these things give us energy.

A child needs the closeness and affection of its family from the very beginning in order to develop well. It starts with loving attention, making it smile and talk, discovering the world on its own two feet. Later, school, hobbies, sports teams and friendships are added and with them new forms of affirmation, drive and community. Over time, the roles change. We ourselves become those who accompany others, in our own family, at work and in everyday life. How many of us have actually experienced what it is like to go for weeks or even months without any feedback from other people, without encouraging words, closeness and conversation?

My tasks on board also include looking after my body - sensing what it needs: food, fluids, sleep or medical help in an emergency. The maths is simple: the energy we put in must correspond to what we use. If this is not the case, we notice immediately. Emotional energy works differently, it is not measurable. Its absence can throw us off balance just like hunger or exhaustion; without it, we lose the ability to deal with fear or stress, to believe in our own performance and to mobilise new reserves.

Nature in its purest form

Over the years at sea, I have learnt how to maintain my inner strength - and recharge my batteries in good time. In the beginning, satellite communication was not available to me - either because it was not allowed in certain boat classes or because I didn't have the budget to pay the horrendous connection costs. So I learnt to draw my energy from what surrounds me; a skill that has sustained me ever since, both at sea and on land.

The entries in my diary from 29 November, in the middle of the Vendée Globe, show how much strength a clear starry night gave me.

RACE BLOG, 29 November

When there is no light pollution, the moon is a powerful source of light. It illuminates the deck, the sails, its silvery glow runs as a shimmering path across the sea. You don't need a torch. The world appears in shades of grey, clearly contoured, almost unreal. It is still cloudy, only a few stars can be seen. The moon keeps disappearing behind the clouds, but can hardly hide itself. Its light burns through the edges, making the clouds look charged, as if they are about to burst. It goes dark for a few minutes, then everything flares up again as soon as the cloud moves on. As the bow ploughs through the waves, the water running over the deck looks like liquid silver. Standing there alone and experiencing these colours, this atmosphere, is a real privilege.

Of course, we experience intense and challenging situations at sea, but at the same time we also experience nature in its purest form. The ocean is extraordinarily beautiful - I am grateful to be able to experience it in this way.

As a sailor, I get to visit places on this earth that few people ever get to see. When we sail the world's oceans, we are travelling in the most pristine of environments. We experience nature in an unaltered state that is hard to find anywhere else. Apart from the track our boat makes through the water, everything remains untouched. It is overwhelming. At night, in the middle of the ocean, the stars can shine so brightly that you can clearly see the deck and the lines in the starlight even before the moon rises. If the moonlight then hits the spray on the bow at the right angle, a so-called moonbow is sometimes created - a rainbow of white and grey tones with a very unique light spectrum that is very different from sunlight.

Pip Hare about night sailing

In many regions of the ocean, sea lights can be observed at night - a form of bioluminescence in which tiny plankton emit light as soon as they encounter movement in the water. The patterns that breaking waves leave on the sea surface look like a glowing chessboard. As the boat glides through the swarms of plankton, the oars leave glittering trails through the water. But the most impressive thing is when dolphins suddenly appear; they swim through this glow like silver torpedoes beneath the surface. Their tracks cross the course of the boat. On nights like this, the boundaries become blurred. You don't know where the sea ends and the sky begins. It feels as if you are sailing straight out into the universe.

"Travelling, eating or going to the cinema alone often arouses pity. But there is a quiet power in consciously being alone."

Out there on the ocean, I can see the night sky as generations before me have seen it. Cosmologist Roberto Trotta speaks of a "canopy of stars that is slowly receding" - displaced by the light of street lamps, floodlights, digital billboards and solar-powered fairy lights in front gardens. The legendary sailor Bernard Moitessier wrote over 50 years ago about his fear of returning to so-called civilisation - where a businessman would even blot out the stars if necessary, just so that his billboards would be more visible at night. Since then, light pollution has increased inexorably. Today, we know much more about the extent to which artificial light disrupts sensitive ecosystems and causes disorientation in many animal species.

Encounters with animals

Such intense moments don't just happen at night: sailing at high speed under a bright sun across a deep blue ocean is one of the most impressive experiences of all. I had some of the best encounters with animals during the day. With dolphins, for example. For many people, they are lucky charms. I don't know anyone who doesn't smile when they show themselves. Almost all sailors go on deck to watch them, no matter how many nautical miles they have travelled.

Dolphins are simply extraordinary. When I'm lying in a calm or travelling slowly, I can often hear their sounds from a great distance: the clicks and whistles penetrate the thin carbon hull long before I even see them. When they finally surface, they are curious and full of energy. Then they swim alongside the boat, dive under the hull and stern, jump out of the water next to the foils. Sometimes adult animals show their young how to approach a boat.

Twice on previous trips - once off the north coast of Spain, once off Argentina - I had a special encounter with dolphins. On each occasion I was travelling on a smaller, slower boat, leaned far over the bow, let one hand glide through the water and spoke or sang softly to a particular dolphin. Both times he stayed close to me for over an hour, attentive and curious, until I could touch his back. He turned on his side, looked at me, swam away - and returned. I had the feeling that the dolphins wanted to know as much about me as I wanted to know about them. Their intelligence and openness still amaze me to this day.

Encounters with albatrosses in the Southern Ocean

I saw my first albatross in the Southern Ocean. Adult animals have an average wingspan of over three metres and can weigh up to eleven kilos. The body of an albatross is reminiscent of the massive fuselage of a cargo plane. It looks too big to fly, and yet it glides effortlessly just above the surface of the water, almost without flapping its wings. Albatrosses often follow the ships and come so close that you can look into their dark eyes. At night, they appear in the light of the moon or emerge from the cone of light that my boat casts over the waves, only to disappear again immediately. I realise that I am only a guest in their world.

During the 1996 Vendée Globe, French sailor Catherine Chabaud was accompanied by a trusting albatross in the Southern Ocean. She named him Bernard, after her great role model Bernard Moitessier. During the lonely and tense weeks at sea, it occurred to her that the bird might be connected to Moitessier in some way. In his book "Godforsaken Sea" about this catastrophic race, Derek Lundy writes how the sailor was confronted with the big questions of life; questions that only arise when you are alone. Chabaud's experience confirmed what many already suspected about the Vendée Globe: This race was far more than a tough, male-dominated test of strength in the extreme conditions of the Southern Ocean. It was also an inner, personal journey.

I have also learnt to draw strength from my experiences in nature. It's not enough just to see these wonders. I try to really feel them, to open up inside and to anchor what I experience deep within me. I draw energy from good times and use it to regain my balance as soon as things get difficult. When I remember them later, they are not flat images, but three-dimensional memories, vivid and multi-layered. When I think back, it's not just the images that return; the positive energy is also there again. In order to really utilise this power, I have to take the time to consciously store it. Just as a ten-second mobile phone video can never capture the true beauty of a sunset, memories also need attention in order to come alive again later.

Mental techniques for single-handed sailing

Above all, it is important to give myself the space to fully arrive in the here and now. I believe that I can do this because I belong to a generation that grew up without the internet and text messages. I started sailing as a young adult and travelled a lot. When I was 20, I worked on charter yachts in the Caribbean. Later, I took part in a crossing from Trinidad through the Panama Canal across the Pacific to New Zealand. None of my school friends had ever had anything to do with sailing. Many thought I was crazy to just sign on while they went to university or started their first jobs. We kept in touch by letter.

I wanted to share my experiences with people who would probably never experience something like this themselves. To really be able to convey all of this, I needed a moment of silence - and my full attention for what was there. Through mindfulness - more intensive perception and conscious feeling - I was able to store the beautiful moments as a resource for difficult times.

I also work with such mental techniques when sailing single-handed. It is human nature to want to share happiness - we are almost automatically programmed to express amazing or moving things. Since I started to consciously record such impressions for later, I have rediscovered their depth when I am alone. Without distraction, without external judgement. I am completely with myself and free in how I experience the world.

Pip Hare draws strength from music

We live in a society in which constant social proximity is taken for granted. Travelling, eating or going to the cinema alone often arouses pity - as if you have to justify it. Yet there is a quiet power in consciously being alone. Watching the sunset on a hill, listening to music and letting it flow through you, being completely with yourself - it's wonderful.

"One of the hardest aspects of months of single-handed sailing is finding the strength to keep going."

My second source of strength is music, one of my greatest passions of all. I can't imagine a world without music. Good music has an enormous energy; it can change my mood within seconds. I listen to a wide range of music, depending on my mood and the situation: from the in-your-face sound of my teenage years to the powerful, timeless soul of Aretha Franklin to a good dose of techno and electronica.

Music accompanies me everywhere. It connects me with people who are close to me and gives me energy when I need it. Before every race, I put together playlists with my favourite tracks - and often friends and family do the same and give me their music to listen to on the way. When I need a moment to lift me up, I put on my headphones or switch on the speakers. A playlist from a friend reminds me of him - and of everything that connects us. Because I've always enjoyed listening to music while sailing, I've started to add my own soundtrack to my experiences. My songs bring back memories of magical moments from previous races - on other boats, in other projects. Music can comfort, inspire and evoke feelings long gone. So the next time you need an energy boost: give it a try!

RACE BLOG, 21 December

This morning is an Aretha morning. Her powerful voice echoes through the boat and turns it into a stage. I sing along, sounding like a hoarse cat. Everything has just fallen into place over the last few days. We've pushed south past the competition and made up a lot of miles in the process. I gave it my all, carried by my favourite songs. I think it's impossible not to get carried away when Aretha Franklin is on.

RACE BLOG, 21 January

Yesterday I steered by hand for the first time in many weeks, which was great. A cup of tea and some good music: Daft Punk, Muse. I sat on deck like that for five hours, steering through wind shifts and waves until night fell. My neck and back became heavy.

Most of the time I'm alone with my thoughts - but I'm not on my own. There is a team on land that is there for me when I need support. The next chapter is all about this connection: how communication works during the race, what is allowed - and who are the people I turn to when I don't know what to do.

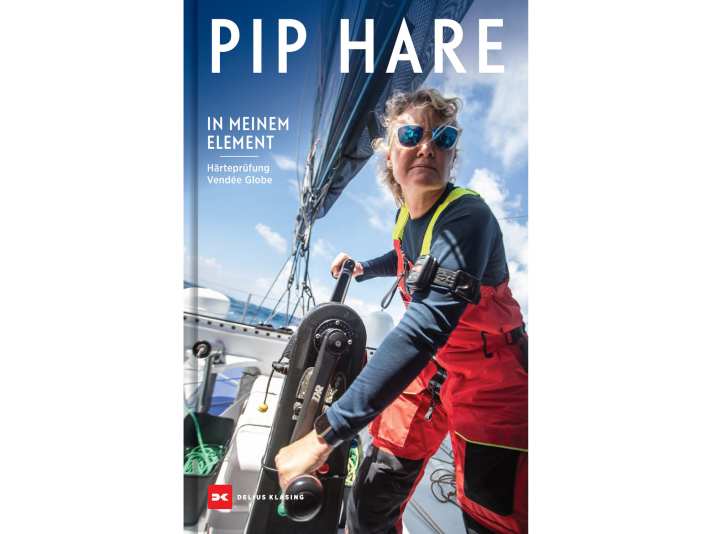

"In my element" by Pip Hare

The biography "In My Element" (Delius Klasing) has been available in bookshops since 5 September 2025 or here in the DK-Shop available.