Dear readers,

Seagrass beds are important habitats for marine life. Many fish species raise their offspring there and mussels, crabs and starfish can hide there. Seagrass meadows can also absorb a lot of CO₂ - an aspect that is becoming increasingly important in the wake of the climate crisis. Researching and protecting them should therefore be close to every sailor's heart. However, the frequent discussion about the negative impact of yachts does not always match my subjective perception, at least in the Baltic Sea.

In addition to all the sporting aspects, experiencing nature is an important part of sailing for me, whether it's dealing with the wind and weather or the unique light moods that can only be experienced on and by the water. That's why the nights at anchor are some of my favourite moments. No noisy streets, no squeaking or squealing fenders and a swim around the boat in the morning instead of a spacy harbour shower.

Even when I was sailing with my parents, the anchor bays of the Danish South Sea were among our favourite weekend destinations and were, so to speak, our adventure playground, which we explored with diving goggles, landing nets and dinghies. What does all this have to do with seaweed?

Well, seaweed and anchoring don't go well together, the green carpet makes it difficult to grip the anchor and increases the risk of drifting when the wind changes. Once broken out, the iron usually collects so many plants that it can no longer hold without cleaning. Hardly any sailor will therefore voluntarily drop the anchor over grass; instead, choose a spot with a light-coloured sandy bottom.

This is where the subjective perception begins, because when I was anchoring in my youth, it was usually enough to pass the three-metre line and the bottom began to shimmer brightly. No matter whether it was Hørup, Lyø, Revkrog near Ærøskøbing or one of the other popular bays. As soon as a good anchor depth was reached, the iron could be lowered - and fell onto fine sand. At best, seaweed was only to be seen in the form of individual patches that could be easily avoided.

More than 30 years later, now with our children, we still enjoy visiting the bays. Today, however, the sandy spots have to be actively sought out. In the depth range between 2.5 and four metres, which is interesting for anchoring, dense sea grass grows almost everywhere. Pure sand, on the other hand, can only be found in much shallower water. And this is despite the fact that the bays are visited by far more yachts than ten years ago. My colleague Andreas Fritsch has had different experiences in other areas.

Of course, individual bays do not give a picture of the entire Baltic Sea, but when seaweed thrives even in areas stressed by yacht anchoring, it is difficult to understand the call for additional protected areas and anchor bans, as proposed in the Baltic Sea Protection Action Plan are listed. Incidentally, the anchors are listed first, well ahead of lack of light as a result of over-fertilisation.

To make it clear: I do not deny that anchors and chains leave marks on the bottom. But I don't think much of blanket bans. Especially as my subjective perception of the development of the seagrass population differs from the picture outlined in the calls for new protected areas. It is often pointed out that the seagrass population has decreased by 30 per cent in the last 50 years.

I cannot explain this discrepancy, but I have a suspicion: the figures do not explicitly refer to the Baltic Sea. In fact, the data on seagrass beds seems to be rather patchy. Comprehensive surveys are difficult or impossible to find and the data that is available is based on aerial photographs, sonar analyses, underwater video recordings and direct observation by divers. Unfortunately, each method has its weaknesses. Echo sounder and sonar systems, for example, can only be used sensibly in water depths of more than five metres, and as the spatial coverage depends directly on the water depth, an extremely narrow search pattern would be necessary for shallow water areas.

The situation is similar with underwater video recordings or the use of divers; only random samples are possible with these techniques. They are therefore usually combined with aerial photographs in order to draw conclusions about the large-scale distribution. However, aerial photographs are also not easy to interpret, especially as the turbid waters of the Baltic Sea often limit visibility to two to three metres. In short, the question of the distribution of seagrass seems to be anything but trivial.

The report from Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania fits in with this. There, the federal government is investing 12 million euros in a research project to map the seagrass meadows along the coast using satellite images for the first time. Based on this data, plans for protection and possible new plantings will be developed. Eight years are estimated for this, which indicates the scope of the undertaking.

The brains behind the Baltic Sea Protection Action Plan will probably not want to wait that long and prohibition zones will have long since been decided. Then it would be a pity if my subjective perception is not so subjective after all and the seaweed in the Baltic Sea is not doing so badly, or at least not in the areas "anchored" by yachts.

Hauke Schmidt

YACHT editor

PS: What are your experiences, have you made similar observations on the development of the seagrass population or do you have a different opinion? Feel free to write to us at mail@yacht.deSubject: Seaweed.

Click on it to see through:

The week in pictures

Recommended reading from the editorial team

New podcast episode

Jens Kroker promotes "different skills" in sailing

Extraordinary lives, courage and the power of sailing: Timm Kruse talks about this with Paralympics winner Jens Kroker in the 60th episode of the sailing podcast

Boris Herrmann

"I love the aggressive lines"

Team Malizia has presented the hull of the new "Malizia 4" in detail for the first time. Boris Herrmann is delighted with the more aggressive lines and explains the plans.

Ghost ships

How the "HMS Resolute" drifted out of the pack ice and into the Oval Office

Ghost ships are usually legends - but the "HMS Resolute" is an exceptional case: rescued rudderless from the Arctic pack ice, she became a diplomatic symbol and lives on today as a famous desk in the Oval Office.

Vendée Globe

"Born to Race" with Boris Herrmann - Aiming for performance

Boris Herrmann and Team Malizia continue their documentary series "Born to Race" with part 2. The new Malizia construction is progressing. The hull can be seen for the first time.

Radar

New examination simulator for professional and yacht skippers

Radar navigation as an additional qualification to the pleasure craft licence. Recently, examinations have been held on a ship simulator for professional skippers.

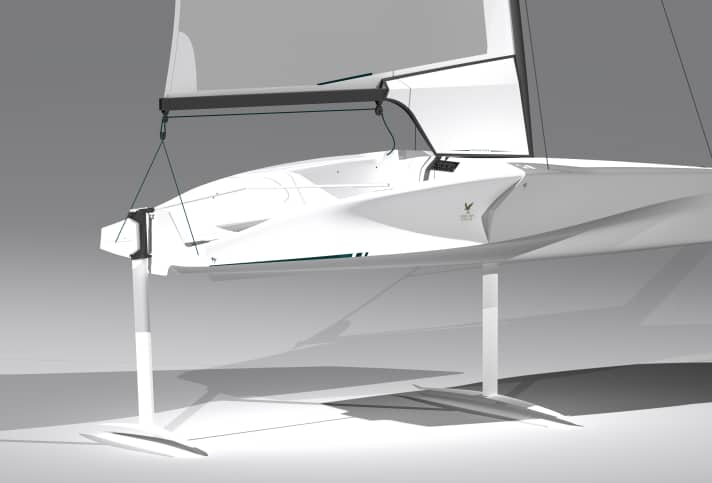

Airborn Foiler

Innovative flying machine with a brain

With the Airborn Foiler by designer Thomas Tison, it is not the helmsman who controls the height and balance of the flight, but a microprocessor via small electric motors. The innovative aircraft is now set to go into series production.

Portrait

Globe 40 skipper Lisa Berger sails around the world from Lake Attersee

Lisa Berger does what many only dream of. The Austrian Globe40 circumnavigator from Lake Attersee is approachable, authentic, persistent and courageous.

Arcona 465 MK II

Consistent fine-tuning with a Swedish signature

Model update at Arcona Yachts. The Swedish shipyard has once again thoroughly revised its long-selling Arcona 465 and is now launching the attractive performance cruiser as an MK II version. And; as before, the boat is available in both carbon fibre and now also in GRP construction.

"Palm Beach XI"

29 knots top speed thanks to C-Foils

The 30-metre racing machine "Palm Beach XI" finally takes off. Mark Richards' supermaxi is currently training in Sydney Harbour with the new buoyancy-supported C-foils and whizzed past the metropolis' Opera House at 29 knots.

DN Ice Sailing

Jablonski ice-cold to World Championship silver and European Championship bronze

The DN ice sailors have crowned their World Championship and European Championship champions. Once again, class king Karol Jablonski returns home with two medals, even at the age of 63.

Newsletter: YACHT-Woche

Der Yacht Newsletter fasst die wichtigsten Themen der Woche zusammen, alle Top-Themen kompakt und direkt in deiner Mail-Box. Einfach anmelden: