Opinion: 35 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall - also a topic for sailors!

YACHT-Redaktion

· 09.11.2024

Dear readers,

It's Sunday, 5 July 1987, two days after the start of our summer trip with the family on my parents' boat. I am 13 years old, excited and quite proud, because we are sailing into the night from Klintholm. And I'm allowed to stay awake and sit next to my father in the cockpit. He has the tiller in both hands and is staring through the darkness at the dimly lit compass.

Our destination was exotic by the standards of the time: we wanted to visit Polish sailing friends in Swinemünde. I had already learnt that you need a visa for this, for which you have to wait a year, and export goods such as whiskey, toilet paper and ladies' tights in order to be cleared in at all. I also learnt before the trip that the reason for all this is the so-called iron curtain and how it came about.

That night, I realise that this iron curtain also seals off parts of the German coast. And not just in one direction.

We sail for hours through the darkness in a light south-westerly wind under main and Genoa I. We sail south-east at a respectable distance from the coast of Rügen. GPS chart plotters for pleasure craft are not yet available. Our pride and joy is the APN 4 installed on the chart table, a Decca navigator from Philips. We regularly record the location shown by this magic box in the logbook and plot it on the nautical chart. This gives us a course along the GDR sea border over the hours.

My father explains to me what this invisible wall means as we are illuminated by one of the 34 ships that, as Border Brigade 6 of the German Democratic Republic, were supposed to prevent its citizens from escaping by sea. It was common practice for the border guards to leave their territorial waters to search the open sea for boats that had escaped undetected overnight, as Christine and Bodo Müller would write a few years later in their book "Über die Ostsee in die Freiheit".

That night I experience it for myself and my father's explanations are a history lesson that tastes salty.

And a little bitter. Because while the typical dull roar of the guard boats is clearly audible, and the bright beam of their searchlights flickers on the horizon from time to time, I learn that we are currently rounding a second German country. "We can't sail there," my father says, "and the way things look at the moment, we're unlikely to see anything change."

Until then, I had only heard of the GDR as something abstract. Now I experience for myself what German division means. A trip to Sassnitz, for example, just a few nautical miles to starboard, is unimaginable.

I've been part of the family crew since I was just a few weeks old. And where haven't we been in those 13 years? Not being allowed to sail anywhere was completely unimaginable for me back then.

Today, I can hardly remember the details of the conversation with my father. But I do remember thinking a lot about how such a thing is possible. On the high seas, and locked out. It was an experience that left a lasting impression on me, who was just starting to take an interest in political issues.

A little later, 35 years ago today, the Wall did fall. It moved me deeply at the time.

If it seemed depressing to me as a young boy not to be allowed to sail across the sea border and call at a harbour on the coast of Rügen, how depressing must it have seemed to the people who were sitting there on their sea-going yachts and not allowed to sail abroad?

I was soon able to speak to sailors from the GDR. We made contact in the winter of 1989/90 and in the summer of 1990 the time had come and for the first time the aim of our summer trip was to sail further along the German coast than had previously been possible. I remember this trip as one of the best of my sailing life. I felt as if the door to a secret garden had opened.

I still remember how exciting it was to call at Warnemünde, a German harbour abroad. To put up the host country's landing stage in familiar colours, but with the emblem of the GDR. Being greeted by officials in the same language when clearing in. And then to be greeted by friends we had made during the winter.

I remember how captivated I was by the landscape as we travelled further into the Bodden waters. They seemed to me like a Schlei that didn't want to end. For days on end, I travelled along reed-covered banks.

I remember the rollercoaster of moods that we were immersed in as we approached the people. From euphoric excitement and joy to the freedom of travelling, melancholy and worries about losing our familiar surroundings, to understandable and very real existential fears.

It was another history lesson that the sailing life gave me, but the flavour was different.

We now learnt first-hand how the sailors had fared during the GDR era. In the tiny harbours, we were usually moored together with only a few of them, we immediately got into conversation, helped each other out, greeted and said goodbye to arriving and departing boat crews and sat together for a long time in the evenings.

The big run from the West had failed to materialise that first summer. But the fear of this was palpable and understandable. I had never experienced such a familiar atmosphere among sailors who didn't even know each other. It was also noticeable that the majority of people had resigned themselves to the conditions under socialism.

The first publications about the GDR sailing world soon appeared. First and foremost was Wilfried Erdmann's enchanting book "Mein grenzenloses Seestück". The circumnavigator, who had fled the GDR as a young man to fulfil his passion for travelling, spent an entire summer sailing through the waters of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern on a migratory bird and mingling with the people there. He repeated the journey 13 years later and drew comparisons in "A German Sailing Summer". The books are valuable eyewitness accounts of reunification.

I was also captivated by the aforementioned book "Über die Ostsee in die Freiheit" as soon as it was published. Christiane and Bodo Müller had taken the trouble to research escape attempts across the Baltic Sea as comprehensively as possible, both those that succeeded and those that failed.

Ten people were known to have lost their lives fleeing across the Baltic Sea when the Wall came down. Current research knows of 135 cases. But how many people really died from hypothermia or drowning on their way to freedom, as Müllers wrote in their book, will never be known. Because the sea knows no witnesses. And that is still true today.

Today marks 35 years to the day since the Wall came down. And with it, the wet border between East and West also opened.

To remind you of this, last week I recorded the story of a Stralsund couple who fled the GDR twice in their national cruiser "Rugia" in 1961 at the last minute before the Wall was built and the resulting total sealing off of the sea border.

From my personal experience as a sailor, there are also good reasons to remember this part of our history.

Lasse Johannsen

Deputy Editor-in-Chief of YACHT

Click on it to see through:

The week in pictures

Recommended reading from the editorial team

Gift idea

Voucher for YACHT Premium as a last-minute present

A gift voucher for YACHT Premium is an excellent last-minute gift for all sailing and water sports enthusiasts for Christmas!

Record from space

Monster wave of 19.7 metres measured by satellite

A new satellite system makes it easier to recognise monster waves. A recently published study shows how storm waves can cross oceans and endanger even distant coasts. The more accurate detection could also improve routing programmes.

YACHT readers' trip

On the "Sea Cloud II" 900 nautical miles through the Caribbean

The multifaceted YACHT readers' trip through the Caribbean dream destination starts on 6 March and takes us through one of the most beautiful sailing areas in the world in ten days.

Shipyard portrait

Pure Yachts produces in small series with big goals

The Pure Yachts shipyard, newly founded in Kiel, focuses on long-distance performance yachts made of aluminium. It can already boast its first successes.

Baltic Sea

Fehmarn Sound Bridge - Reduced clearance height

Watch out for the mast stop! The clearance height of the Fehmarnsund Bridge has been reduced until summer 2026. Due to construction work, only 20 metres are available instead of the usual 23 metres.

M.A.T. 11

The Orient-Express is set to become the new ORC pick-up

Hot racer from the Orient. The M.A.T. 11 is set to create new excitement in the ORC scene. The design comes from Matteo Polli.

Shadows in paradise

Brutal attack on expedition boat in Papua New Guinea

The first motorless circumnavigation of Antarctica by sailing boat was abruptly interrupted by a brutal robbery in Papua New Guinea. The expedition ship "Zhai Mo 1" was badly damaged and looted, putting the voyage of the Chinese sailor Zhai Mo on ice for the time being.

Dispute over measurement

ORC and X-Yachts agree on cooperation - joint statement

Due to the debate surrounding the XR 41, the Offshore Racing Council (ORC) is reviewing its algorithm for calculating race values.

Hallberg-Rassy 370

Sailing and living at the highest level in the YACHT test

With the Hallberg-Rassy 370, the Swedes present a cruising yacht that leaves almost nothing to be desired. We have tested the first model.

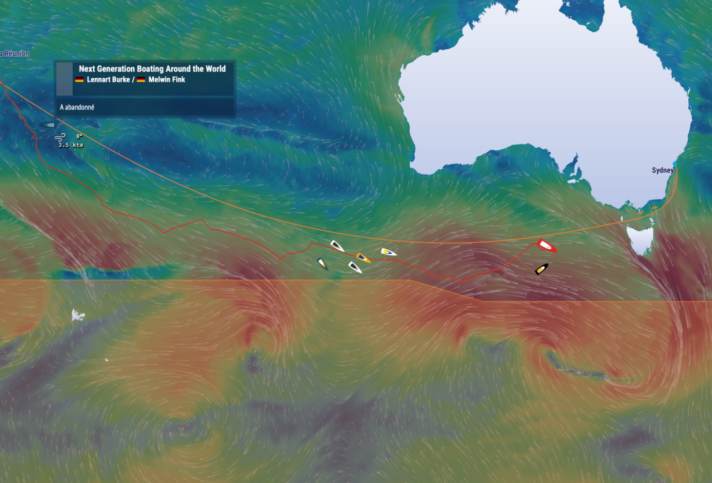

Globe40

On course for La Réunion - concerns about the mast remain

Lennart Burke and Melwin Fink are on their way back to La Réunion in the Globe40. While the competition is aiming for Sydney, the GER duo are fighting on all fronts.

Newsletter: YACHT-Woche

Der Yacht Newsletter fasst die wichtigsten Themen der Woche zusammen, alle Top-Themen kompakt und direkt in deiner Mail-Box. Einfach anmelden: