Archaeologist Greer Jarrett from Lund University recently proved that adventure and science do not have to be opposites. He wanted to find out how the Norsemen navigated over a thousand years ago, which routes they used and where they moored. A sailor by trade, he quickly transferred his research to the water because, according to Jarrett: "The Vikings were a seafaring culture."

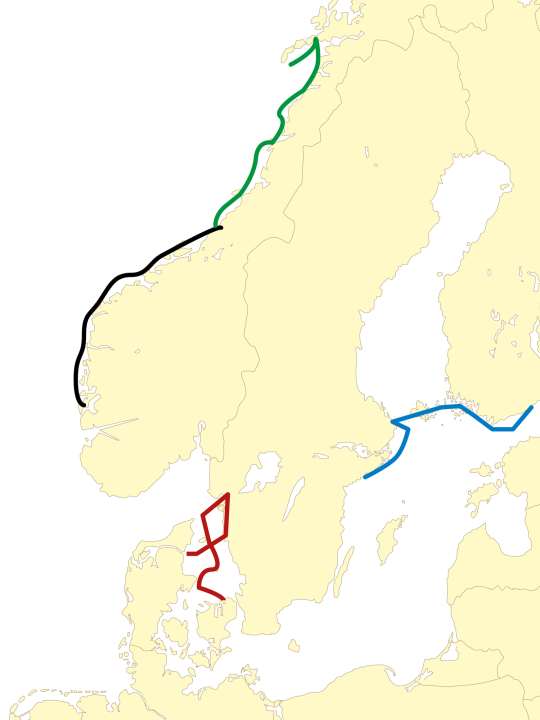

He left almost 2,800 nautical miles in his wake along the Scandinavian coasts - largely dispensing with comfort and modern technology, in open Nordic clinker boats with square sails, whose ancestors were already used by the Vikings.

Also interesting:

The Fyring or Fembøring boats heel very little, are light and flexible. They barely dip into the waves, but "a boat like this lies deep in the water and there is no deck," says Jarrett. "So you sit very close to the water and the simple rigging makes the forces directly perceptible," says the researcher, describing the first approach to the Viking sailing experience. The boats offer hardly any comfort. No plotter, radar or AIS, no pantry, toilet or heating, the Fyrings don't even have a cabin.

Jarrett has cameras and a GPS on board to collect data. They initially navigate using nautical charts and a compass, and even buoys and beacons cannot be hidden from view. However, Jarrett and his crew do not use them wherever possible - they want to recreate as authentically as possible how seafaring worked when there weren't even nautical charts.

They initially do this on day trips. Jarrett doubts that the old Viking boats couldn't tack. In fact, tacking turns out to be a team sport when the sail kills and the sheets beat in a wild dance. Then four crew members pull with all their might on the leeward sheet, mainsheet block, fore and aft leech until the sheets are back on the vang. Despite this, they cruise through a six-mile-long sound - at a maximum of 59 degrees to the wind. "Four hours and 60 tacks later, we knew that it was possible, but a lot of work!" says Jarrett with a laugh.

2,790 nautical miles for research

It is autumn on the Trondheim Fjord and the weather is cold and wet when, for the first time, they no longer wonder how many miles it is to the harbour, but how many hours. Wind, weather and tides are calculated over the thumb, the idea of absolute distance fades. For orientation at sea, the Vikings divided the horizon into at least eight arcs around their ship and gave them names.

Within these rather roughly defined sectors, they orientated themselves using "mental maps", which were passed down through generations exclusively in the form of stories and legends. They tell of characteristic coasts, mountains or islands, of currents, typical weather conditions and of seabirds, seals or whales that became signposts during their migrations.

The researchers also develop a kind of mental logbook and sail intuitively based on experience instead of course lines or compass courses. The boat becomes the only fixed axis of orientation as it rocks against the sublime backdrop of the Norwegian west coast, with land and sea rising and falling all around, appearing and disappearing behind curtains of weather and rolling waves. Compass and map are obsolete, as is a fixed sailing plan.

Unknown harbours of the Vikings are discovered

By "carrying out experimental trials under sub-optimal conditions", as Jarrett tongue-in-cheek calls the training sessions, the crew says goodbye to fair-weather sailing and gets close to the reality and perception of the ancient Vikings.

It looks dangerous when waves break on steep coasts and spray rises metres high, but "the routes were okay as long as we travelled further away from the coast. The sea is deep there, the waves are not so steep and there are no downdraughts and strong currents," says Jarrett - in stark contrast to the fjords, which can become a trap for square-rigged sailors if the conditions are not ideal. This leads him to conclude that the Vikings tended to head for offshore islands or skerries, which were more than 2.50 metres deeper than they are today. He searches there - and actually discovers some previously unknown Viking harbours.

"With a good weather window, the world is not such a big place."

Once familiarised with the boat and the intuitive form of sailing, the crew set off for the Lofoten Islands. Day and night, they fight their way beyond the Arctic Circle. "We sailed in spring, but it still rained and snowed on 13 out of 17 days," reports Jarrett.

The associated mood becomes a bigger challenge than the cold. Four hours on watch are just short enough to avoid freezing through completely and then warm up again close together in the cramped bunk. They are rewarded with a north-easterly wind and sunshine on the way back. "We sailed back in a straight line in less than three days," enthuses the Scot. "That shows: If you choose your weather window well, the world isn't such a big place."

He then explores the coast towards Bergen and an old route from Sweden to Finland, before setting off on a fyring to the Kattegat, following an old Viking trade route from southern Norway to Haithabu on the Schlei.

Viking routes by visual navigation

The Skagerrak with its strong westerly winds and high waves pushes the small Fyring to its limits for the first time. The assumed route is to follow the Swedish west coast closely, but this proves not to be a good idea here either: the current sets strongly northwards close to land and the rocky coast is threatened by leeward waves in westerly winds. "The Baltic Sea is shallow compared to the Norwegian coast, so sea conditions can change much more quickly," he says, describing his experience. "A calm sea in the morning can turn into high waves in just a few hours."

Islands and headlands or the clouds above them show the course - but Skagen, Læsø, Anholt, Djursland or Sjællands Odde come into view shortly after casting off and can be navigated in relatively straight lines even without a compass. Jarrett concludes that the routes between western Sweden and the Oslo Fjord probably ran via Læsø - which is mentioned as Hléysey in Norse poetry and sagas -, Anholt and Samsø. In Viking times, these islands were little more than large sandbanks. But if you head for them today, you can do so with the feeling of being on the trail of the Vikings - and perhaps forget the plotter, nautical chart and compass for a moment.

Traditional research boats

Greer Jarrett sails boats such as the Fembøring - "five-oarer" and Fyring - "four-oarer". The Fembøring measures around thirteen metres, the Fyring around nine metres. They are built in clinker construction from the keel upwards, with the planks overlapping. The boat builders sometimes still use old techniques such as splitting planks from the trunk to follow the wood fibre. The planks are joined with iron rivets and the frames are inserted afterwards. This gives the boat its characteristic shape. The construction method developed in Scandinavia more than a thousand years ago and boomed during the Viking Age from around 800 to 1050.

The descendants of the Viking boats were used for fishing and transport until well into the 20th century. In Norway, they are still sailed by enthusiasts and fishermen today. What has remained the same since Viking times, apart from the design, is a flexible, "working" hull, low weight in relation to size, good seaworthiness and a combination of rowing and sailing ability - ideal characteristics for the rugged coasts with fjords, skerries and changeable conditions.

Ursula Meer

Redakteurin Panorama und Reise