It was the summer of 2011 when 14-year-old Mathis Menke and his friend Merlin Moser, who was a year older, took the plunge: together they tinkered with a small two-man dinghy and fitted it with a harness. However, what started out as a promising fun project ended abruptly: the small sailing boat sank on Lake Ratzeburg during its maiden voyage. If this wasn't the beginning of a very special story, it would probably end abruptly here. But Menke remembers: "We were helpless in the water when a moth sailor came and rescued us. We went to him on land with a bottle of wine and thanked him."

Since then, the two childhood friends have each designed and built three foiling Moths themselves. The current design is not only finished to the highest standard, but was even ahead of the extremely rapid development within the construction class in the meantime.

Also interesting:

After his extraordinary first contact with the class, Menke started out in a purchased lowrider. He remained in the water for two seasons before taking to the air following the development of the class. "Flying for the first time was very special because it took you out of the water and into a new dimension. Everything suddenly became very quiet around you and your speed increased rapidly. It was an extremely exciting feeling," he says, describing the new way of sailing.

Foiling moths fly through all manoeuvres these days

When the Moths began to fly in the early 2000s thanks to so-called hydrofoils, hardly anyone in the sailing world realised how revolutionary this step really was. Even in 2006, when a report on the strange flying machines first appeared in YACHT, today's speed standards for the class would probably have been described as utopian. Only six sailors in the world are said to have been able to stay on the hydrofoils while jibing. Today, this has long been mandatory in order to avoid having to go home with the red lantern, even at regional regattas.

For some time now, Mathis Menke has even been flying turns. "I usually fly all manoeuvres," explains the 27-year-old. The current aircraft can also reach a top speed of up to 35 knots. Moths have therefore gone from being a tinkering class with an increasingly high average age to an elementary training device for the most successful America's Cup, Olympic and SailGP athletes. The original tinkerers who have always characterised the class, on the other hand, seem to have become a dying breed.

As members of the first young sailors, Menke and Moser also marked the beginning of the hype surrounding the class in Germany. However, they bucked the trend and joined the ranks of the dying hobbyists almost from the start. Even today, they are among the few remaining self-builders. "Originally, many more Moth sailors built their boats themselves. There are currently only one or two left in Germany," states Menke.

The decisive factor for them, as for many others, was the enormously high prices for the boats. The dinghies, which are only 3.35 metres long, can cost over 45,000 euros fully equipped these days. "Basically, the Motte is very, very expensive compared to other boats. This is also due to the fact that a lot of development has gone into it and the materials, such as carbon fibre, are extremely expensive and the manufacturing processes are complex." In addition, the boats are not manufactured in low-wage countries, but primarily in Western countries.

Learning by doing to build your first DIY moth

After the two youngsters were outclassed at the 2015 European Championships with second-hand Moths, it was clear that new boats were urgently needed. However, the students could not afford competitive designs at the time. And so, without further ado, they started building the first two boats.

Plans were made and moulds produced without any experience. "We built them at home, in the workshop, but also in the boiler room or laundry room on two or three square metres," reports Mathis Menke. The duo has been driving the project forward for over two years with a little support and a lot of learning by doing as well as an enormous amount of time. "It's not something you do on the side. We spent every spare minute on it."

In the end, the boats made of carbon fibre flew, but the builders were not satisfied with the result. Menke recalls: "The first boat had a banana-like shape and we focussed mainly on the structure and not so much on the control mechanisms." Both of these later became a problem, which is why the decision was made during the final construction phase to design another moth. "We adapted the hull shape and paid more attention to the trim systems, resulting in a much better functioning boat in the second generation."

In addition to the experience from the previous construction, one circumstance in particular had a positive influence: During construction, both sailors began their studies in shipbuilding and maritime technology at Kiel University of Applied Sciences. They were able to apply their newly acquired knowledge immediately. Menke confirms: "The learning curve was steep." Among other things, they began to work on the boats more and more professionally with milling and 3D printing. "The programme has had a huge impact on how the quality of the boats and the construction has changed."

While hand drawings and templates initially determined the design, the use of CAD engineering software later played a key role. With the same hull shape and the adaptation of a few fine details, as well as thanks to new manufacturing techniques, the current self-build moths completed in 2022 are on a par with high-quality production boats. And not just in terms of the impressive build quality, but also in terms of the boat design and numerous technical refinements.

Own developments hit the nerve of the times

The chosen hull shape alone was not common at the start of construction of the second generation: the self-builders from Lake Ratzeburg opted for a line that was already designed for the so-called deck-sweeper sails, which are pulled down to the deck. Menke explains: "When we were finished, we were lucky that the other manufacturers were also pushing ahead with their development in precisely this direction, so we were right in tune with the times."

The situation was similar with another radical design decision: Inspired by other self-builders, Moser and Menke reduced the surface area of the wings on which the athletes sit and ride out while sailing. This significantly reduces aerodynamic drag. "It simply makes technical sense. That's why we were relatively sure that we were on the right track. But of course you never know," says Menke looking back. A short time later, the short, steeper booms became the standard at all major shipyards.

Another clever detail can be found in the centreboard box. While commercial manufacturers always give it the shape of the current foil profile, Menke and Moser opt for a far more sustainable variant: the centreboard box of their boats is a generously proportioned rectangle. This means that a wide variety of profiles can be fitted into the boat without any major modifications. These are simply fitted with a matching rectangular inlay. As the innovations in the hydrofoil area in particular are decisive for competitiveness, the boats can be brought up to date relatively easily at any time in this way. For example, experiments are currently being carried out with stainless steel and titanium profiles. Due to the material properties, these can be made even thinner and sharper - which undoubtedly results in higher speeds.

Other areas are also constantly being optimised. "We now have the entire boat as a 3D model. We use it to plan every stage of development and every innovation. We have even simulated the cords on the model. This allows us to rethink the entire system," says Menke. Sometimes, however, unwanted changes are made to the boat. This is when there is a breakage.

Half a moth on regattas as a replacement

The passionate Moth sailor admits: "At a regatta, there's always someone who suffers some kind of damage to the boat." However, hardly anyone is as well equipped and trained as Menke. His trailer, which he uses to travel to regattas and other events, is equipped with a considerable workshop.

"I've installed a workbench with a vice and always have various spare parts and equipment with me, including a vacuum pump," says Menke. This means he can react quickly at any time. Last but not least, a tent is included so that there is also a place to sleep. "This trailer actually contains everything a moth's heart desires. And when the lid is folded down, I can load my boat on top."

Continuous further development and half a boat on board at all times as a replacement - however, despite being self-built, moth sailing does not seem to be really cheap. If you then factor in the labour involved, no significant money has been saved over the three generations of boats. The owner also confirms this. Nevertheless, he would do it all over again at any time. "We've learnt an enormous amount in all the years we've been tinkering and building." That alone is priceless.

Above all, he hopes that the class will continue to develop and grow. "I don't just go to a regatta to sail, but also to meet like-minded people and have a good time." The approximately one hundred members of the German Moth Association feel the same way. "The class is very active and the development in recent years has been really positive," says Menke, who holds the office of Vice President. His construction accomplice Merlin Moser is the new First Chairman.

According to Menke, the different approaches within the class and the demand for high performance do not contradict the common spirit of togetherness. "There are hobbyists, there are amateurs of all ages, and there are professionals such as Philipp Buhl, who actually sails at the Olympics. They all come together at the regattas and there's no distinction made."

They sail together and help each other ashore. That's what makes the class. "The atmosphere is informal and even the absolute beginner is not left out in the rain when they get somewhere for the first time," explains Menke, who has come a long way in the class himself. He is now not only one of the most gifted self-builders in Germany, but also one of the fastest flyers on the water. But he is far from finished learning. "There are always things you can improve. On your own technique, on the manoeuvring sequences, but above all on the trim of the boat," he says.

Three times a week during the season, he goes out on the water to stay at the front. Menke: "Being a construction class means you're constantly dealing with new developments. That means you don't sail the same boat all the time, but basically a new one every year."

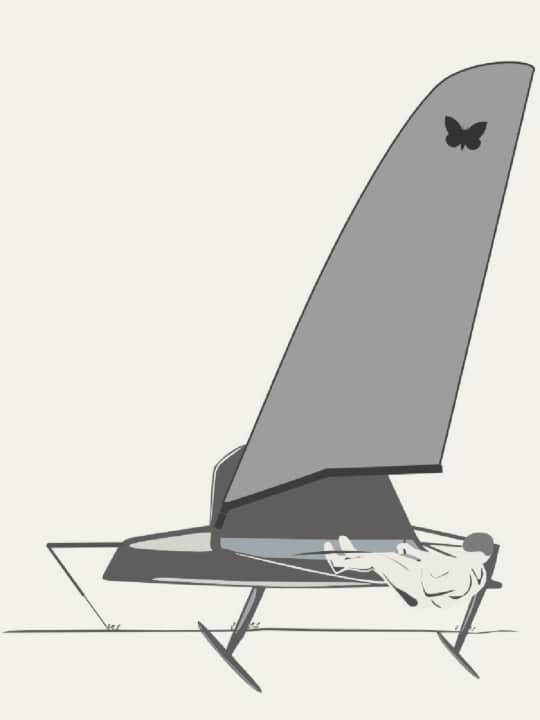

Technology: How the moth flies

An ingenious system keeps the featherweight butterfly at the same distance above the waterline at all times

The Motte is regarded as a major driver of innovation in the field of foiling. The introduction of the altitude control system was also revolutionary at the time: A rod attached to the bow scans the waves. If the boat is in displacement mode, the so-called wall also lies on the surface of the water. In this state, a mechanical connection provides maximum buoyancy at the flap of the main foil. If the boat lifts out of the water, the rod can swing out forwards and thus causes the flap setting to be adjusted up to downforce so that the boat does not shoot out of the water. The flight attitude can also be adjusted by turning the tiller arm.

Technical data of the moth

- Total length: max. 3.35 m

- Width: max. 2.25 m

- Mast height: max. 6.25 m

- Weight: 30-45 kg

- Mainsail: max. 8.25 m2

- Yardstick number: 72

Max Gasser

Editor Test & Technology