Autobiography: How Seamaster Award winner Craig Wood became a solo sailor

YACHT-Redaktion

· 21.01.2026

Five days later I reached the marina. The thermometer barely climbed above 5 °C. My breath formed a small, hot cloud in front of me. It was freezing cold. All the sonar boats were ready on the jetty, sails and lines were ready to be rigged. I smelled salt in the air and the odour of washed-up seaweed. Just being near the water gave me a tingling sensation.

I looked up and saw my Paralympic sailing coach coming towards me - despite his broad grin, he looked at me with concern. "You can't sail with those stitches in your nose, Craig. I can't let you do that," he said, rubbing his hands to warm them. "Okay," I said, but thought that nothing could stop me from sailing today.

More about Craig Wood:

While the coach was already instructing the others in my group, I went to the men's toilets. If I wasn't allowed to sail with the stitches, there was no other choice. The stitches had to come out. I had everything with me - when you're in hospital, you always have everything with you - I just needed a mirror. In the bathroom, I leaned against the window to take a closer look. It was done quickly and the wound was almost healed anyway. I took my surgical tweezers, lifted the knots of stitches, cut them with the scissors and pulled them out one by one. Done. My trainer had almost finished the meeting when I came back.

"I've removed the stitches," I said and proudly showed him my work. "Seriously?" he asked, stunned. "Yes, I was supposed to go to hospital to have them removed, but I have the same set here, so it wasn't a problem." "I can't believe you did that." The coach didn't know what to say. I watched him think for a moment, wondering what to do. "All right, then. As soon as you get cold, we'll stop," he said. I think he had realised what the training meant to me.

"I couldn't keep running to the hospital as soon as something unusual happened."

There were three of us in the seven-metre keelboat, with me the two war veterans Luke and Steve, who had both legs amputated and were sponsored by "Help for Heroes". I was responsible for the mainsail trim, Luke was to steer and Steve was to take the jib sheet and call the wind. We cast off from the pontoon and quickly picked up speed. We were soon zooming over the waves, tacking and gybing and sailing figure eights. It was marvellous. I was even allowed to take the helm myself.

After about an hour and a half, I suddenly felt terribly cold, but I didn't say anything. I didn't want to get off the boat. A few minutes later, my coach saw me from a distance and raced up in his motorboat. "Oh my God! Craig, you have to get out of the boat, jump in my rib!" he shouted. "That's a bit risky, isn't it?" I replied, because jumping from the keelboat into his rib could easily have ended in the water for me. "OK, I'll throw you a tow rope, you get the sails down and all get in."

"Oh, it's all right, coach, I can sail too," I replied. But he insisted, so I took the rope.

We drove straight back and moored up. The coach disappeared ahead while I walked from the slipway towards the car park. Seconds later, he reappeared with a silver rescue blanket. "Well, what's this all about, mate?" I asked, but he didn't let me stop him and started wrapping the blanket around me in front of the rest of the team. I felt stupid. The whole thing was a bit over the top. "You need to look in the mirror," the coach said, pointing at my nose. I pulled my mobile phone out of my pocket and switched to selfie mode. "Ah," I said. My nose was all blue. "I think we need to take you to hospital." I laughed. He must have thought the stitches had caused my nose to die. "Oh no, mate, of course not. It's just a circulatory disorder due to the cold." I took off my prosthetic arm to show him. The stump was purple.

"That's normal for amputees," I said. And it was true. I couldn't spend my life running to the hospital every time something unusual happened. I had been working towards this day for three years, and now it was time to stop putting myself in cotton wool or being put in cotton wool.

"Being blown up in Afghanistan was the best thing that ever happened to me."

While my coach was getting his lesson in amputee blood flow that day, I got a regular training spot with Luke and Steve as a three-person sonar team. I was over the moon. This meant regular training sessions with the aim of being part of Team Great Britain at the 2020 Paralympics in Tokyo. I was to be the helmsman, Luke would trim the mainsheet and do tactics, and Steve would sail the jib sheet and tell the wind direction and strength.

I really enjoyed the Paralympic training camps. I travelled a lot and met lots of interesting people. During one of these camps in 2013, for example, I met a blind sailor who was about the same age as me. He later inspired me to develop my skills and move from small keelboats to larger vessels. His name was Liam.

Liam took part in the Paralympic sailing camps after winning the World Blind Sailing Championships. I met him at a social gathering in an Irish pub in Cowes. "Let's go round and get to know each other better," said one of the lads. "Liam, you go first!" All eyes turned to the handsome, six-foot-four, brown-haired man in his early twenties sitting next to me at the table. "How did you get into sailing?" I asked. He took a sip of San Miguel before answering: "I've been sailing since I went blind as a teenager five years ago." Liam was likeable, but seemed nervous. He took another sip of beer, kept his introduction short, and the group continued round until it was my turn.

"My name is Craig," I said in my usual strong Yorkshire accent. "Getting blown up in Afghanistan was the best thing that ever happened to me." Everyone fell silent. Liam moved slightly to the side and straightened up to hear what I had to say. "If I hadn't lost my legs and my arm, I'd be sitting bored in the office right now, but instead I'm here trying to qualify for the Paralympics," I said, grinning. I saw Liam nod; he understood what I meant.

"And you, Craig - do you want to sail round the world one day?"

A few hours later we got chatting and it turned out that we both sailed on Sonars. As Liam had just won gold, I peppered him with questions about how he gets the most out of the boat. "I'm just the jib trimmer," Liam explained. "It's all teamwork. Good communication, things like that. Sailing is perfect for me. I can feel the wind and hear when the sail needs trimming."

Liam suffered from the rare genetic retinal disease retinitis pigmentosa (RP) and the specialists categorised his vision as "less than 10 degrees", as he was completely blind in one eye and had only 15 percent of his peripheral vision left in the other. Liam himself described his situation as feeling like he was looking through a straw and that he would eventually go completely blind. RP affects men and women differently. Men can suffer severe vision loss from birth, whereas women are affected later, if at all, as the condition is located on the X chromosome. Sometimes, however, this extra X chromosome becomes inactive in women in the course of their lives, leading to a later loss of vision. This is what happened to Liam's mother, who went blind in her mid-forties and had three sons before she even knew she had the condition.

"What else do you want to do?" Steve asked Liam. "I mean, apart from the Paralympics." Liam thought for a moment. "Sailing round the world would be amazing. I'd like to do that one day. I've always thought I should travel while I can still see something."

Liam looked at me and scratched his chin. "And you, Craig - do you want to sail round the world one day?" I downed the rest of my drink and exhaled slowly as I pondered the question. "I don't know. I like sailing regattas far too much," I replied after a while. "The sonars are easy to handle. I'm not sure if it feels the same on a yacht."

"Oh, that's right," Liam explained. "Not quite the same, but still great fun."

A Paralympics team is forming around Craig Wood

We chatted for the rest of the evening and I kept in touch with Liam. When Luke told us that he wanted to spend more time with his young family, it made sense to offer Liam his place at the next regatta. Liam was thrilled. This was his chance to make the Paralympic team. "Absolutely!" he said without hesitation.

A few weeks later we travelled to Medemblik in West Friesland, Netherlands, to see if we would work as a team. I was to stay on the tiller but take Luke's tactical role, while Liam would be in charge of the mainsheet trim. Steve stayed in front, operating the jib sheet and calling the wind. Liam initially felt out of place as he was the only one who could fully move his limbs and wasn't a former soldier. However, Steve and I endeavoured to make him feel welcome.

After some time on the sailing boat, we discovered that we had things in common, even if we didn't have the same disability. We each had our strengths and weaknesses, but the combination worked well. Where Liam had difficulty seeing, I called out instructions. And when we weren't physically as fast, Liam would immediately lend a hand, grabbing a loose line or switching sides to change the weight trim. Together we had the skills of a healthy person.

Real teamwork. That's what Paralympic sailing is all about. Disabilities are categorised on a points system from one to seven, with one being the most severe. Liam had five points for his visual impairment, Steve had four for his bilateral transfemoral amputations, and I was categorised in sport class three due to my triple amputations. Together we scored twelve points, with 14 points being the maximum in the three sonar class.

From regatta to long-distance mode

It was an incredible week. We finished quite low down the leaderboard, as expected, but the team dynamic worked and a few weeks later I called Liam again to ask if he wanted to sail with us full time and compete for the 2020 Paralympics in Japan. "Help for Heroes would sponsor us and we would start training immediately three weeks later in Weymouth. All year round, with just three weeks' holiday. For the next seven years. Travelling the world and competing. "Hell yeah, man! YAAA!" Liam almost shouted into the phone. He was beside himself with joy. But our enthusiasm didn't last long. A year later, during a regatta in Florida, I learnt that our sailing class was no longer qualified for the 2020 Paralympics.

What a disaster! The only chance of Paralympic sailing would have been the 2016 Paralympics in Rio de Janeiro. But it would hardly have been possible to get fit by then, as our training programme would have been shortened by four years. What's more, there was already a British team that was faster than us. I still did my best and even secured funding for a private coach, but in the end it wasn't to be. The final blow came at the 2015 World Championships in Melbourne, Australia, after the three of us had achieved good placings but weren't fast enough to qualify. My dream of riding for Team GB in Rio was shattered. I was devastated and drowned my sorrows in a pub with Liam.

"Dude, what are we going to do now?" I asked, nervously playing with my prosthetic arm, which looked like a mushroom head made of rubber and which I often used for sailing. "I don't know. Maybe you'll buy a boat and sail around the world," Liam joked. "Yeah, what the hell," I smiled. I still wasn't convinced that bigger boats would give me the same buzz as the Sonar. "Now that 2020 is out, there's no destination."

"Hmmm." I thought about the idea of sailing round the world. "I don't know. I don't quite see the appeal."

Just a few days later, by pure chance, I got the opportunity to sail on a 17 metre Ferrocement yacht. "You were right, mate," I said to Liam when we were back on land, with a big grin on my face. "That was amazing! Sailing around the world is just a bloody brilliant idea." Liam laughed. "I knew you'd love it."

"Let's go!" I said. "Forget the Paralympics. I'll buy myself a yacht and show you the world instead." It was time to really push my physical and mental limits.

About Craig Wood

The British Afghanistan veteran lost both legs and his left arm during a deployment. Since then, sailing has helped him fight his way back to a life worth living. An enthusiasm that drives him to top performances despite his handicaps. In his unrivalled career, Wood has scaled one summit after another. Most recently, he was the first triple amputee to sail solo across the Pacific. He has now been honoured with the title of "Seamaster of the Year 2026".

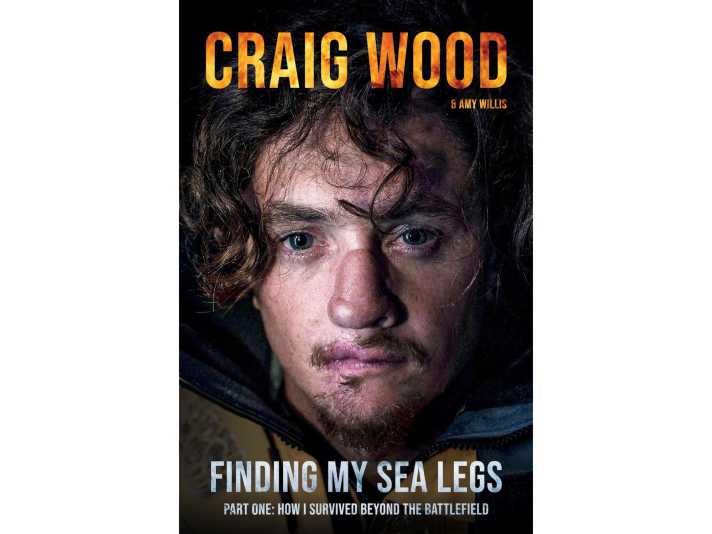

About the book "Finding My Sea Legs"

In his autobiography, Craig Wood describes how he is living his dream of ocean sailing despite injuries, reuniting body and soul. A true story of mental strength, in English with British humour. Bonito Books, 26 pounds sterling. bonitobooks.com