Click here for all articles

- Harald Schwarzlose and Konrad Delius

- Marianne Nissen, Svante Domizlaff and Bobby Schenk

- Hans Günter Kiesel, YACHT photographer

- Lars Bolle, Editor-in-Chief digital

- Jochen Rieker, Editor

- Fridtjof Gunkel, Deputy Editor-in-Chief

Marianne Nissen, Editor BOOTE

Late nights with lots of mocha and tobacco"

From the early beginnings at Potsdamer Platz to the Schleswig era: how A. G. Nissen shaped YACHT over the decades

Alte Potsdamer Straße 5, Berlin-Tiergarten, was a top address before the Second World War. This was the location of the shell limestone-clad "Weinhaus Hut", the place to go for a good glass of wine in Berlin. However, when my father, A. G. Nissen, visited the address, he was not primarily interested in a glass of exquisite wine, but in visiting the editorial office of the magazine "Die Yacht". This resided above the wine house with its editor Karl Jasper.

My father was a graphic artist and painter in Berlin, but above all a sailor from the Flensburg Fjord, with apprenticeship years in the Flensburg Sailing Club. He had sailed in the Atlantic Regatta on the "Aschanti" in 1936 and in 1938 he helped to sail the "Roland von Bremen" to the USA. The Berlin lake district had been part of his everyday sailing life since studying art in the capital. He worked as an illustrator for Karl Jasper.

From then on, the simple columns of YACHT were adorned with small vignettes in which everything was just right: the hull in the wave, the sail position before the wind, the yacht at the cross. In 1938, Günther Grell took over as editor-in-chief, and it was this passionate hard worker who revived YACHT in Schleswig an der Schlei under the most modest conditions after the end of the war; first as "Segler-Nachrichten", then as "Yacht-Nachrichten", and finally under the old name, which was initially banned by the occupying powers. The first post-war edition appeared in January 1949, on the simplest paper with just a few pages.

My father also had to leave Berlin and, after 1945, returned to live in his birthplace of Rinkenis on the Flensburg Fjord - not far from his friend Günther. The two of them now met regularly and spent days and nights producing the YACHT issues, with lots of mocha and tobacco. Grell wrote, my father drew.

Photos were rare on the practically ad-free pages, but Nissen drawings, sometimes illustrative, sometimes technical: of the various rigs, international metre classes, skerry cruisers, cruisers with their respective marks, and of course also of the Olympic classes and the regatta courses of Kiel Week. Man-overboard manoeuvres were common, as well as tacking in heavy seas. My father enjoyed making full-page drawings according to the motto "What's what?": Boom, clew, jib sheet, shrouds, frames, battens - everything to look up, find and learn. Such sections in the YACHT were like miniatures of "Die kleine Seemannschaft". As early as 1949, the two of them bundled their concentrated sailing knowledge in this book - Grell with well-founded, yet amusing texts, A. G. Nissen with what felt like a hundred detailed drawings.

My father also lent his face to YACHT with many a title after the war. He also designed numerous books for Delius Klasing Verlag. This era lasted until the sixties. Then the editorial team moved from Schleswig to Hamburg. A new era began: Photos replaced the Nissen line, the one-man Grell office was replaced by a larger crew.

And the "Weinhaus Hut"? Alongside the legendary Esplanade Hotel, it was the only building on the completely bombed-out Potsdamer Platz to remain intact, thanks to its robust steel construction. However, "Die Yacht" never returned to its first address. To this day, the editorial office has never again been located above a renowned wine bar.

Svante Domizlaff, YACHT author

The interview with Éric Tabarly that I conducted in the shower"

The highlights of Svante Domizlaff's 50 years as an author - and why Horst Stern remains unforgotten for him

YACHT has been with me for most of my life. I was already reading it when I couldn't even read properly. And I wrote for it when I couldn't even write properly. These events have remained a special memory for me:

In 1930, my father Hans Domizlaff was the first German sailor to reach the North Cape with a yacht and published a series in YACHT about his journey with "Dirk III". He later discovered the Côte d'Azur for readers with his motorsailer "Triglav". Publisher Konrad Wilhelm Delius was therefore always a welcome guest on board. This was also the case one summer evening in Arnis in 1958. After a humid and cheerful visit, the elegant gentleman from Bielefeld walked down the gangway, took a wrong turn - and plunged into the dark waters of the Schlei. He was gone. Screams, silence, then a snort, finally relief: a successful rescue! "Aha," I thought, "so that's the man who owns the YACHT."

Although I had no journalistic training, 15 years later I became an employee of Konrad Wilhelm as an editor. The Hamburg editorial office was located on the upper floors of a private house on Neue Rabenstraße near the Alster in Hamburg. There was great excitement on the very first day. The landlady of the property had been found lying in her blood behind the front door that morning. The axe was still lying next to it. What a debut!

A year later, in 1973, I was the only German journalist to witness the magnificent victory of the local Admiral's Cup team with the yachts "Saudade", "Rubin" and "Carina". The sailing world was blown away. So there was a lot for me to report on, not least because Prime Minister Edward Heath, the British team leader, had got lost in the fog with his "Morning Cloud".

In 1976, YACHT sent me to the Olympic sailing regattas in Canada. A glorious time! Germany (West) won two gold and one bronze medal. Head of delegation Otto Schlenzka, legendary Kieler Woche boss and world war-tested naval officer, got salt water in his eyes on the freshwater course. Germany (East) won gold and bronze. However, the SED superiors only received the report late because their local correspondent, a real dragon, had fallen off the jetty. ID card gone, accreditation gone, no line free to phone the success of her gold medallist Jochen Schümann, 22, back to his socialist homeland. We returned her pass the next day ...

In the late seventies, YACHT reached its highest circulation with 124,000 copies sold. The magazines regularly ran to more than 200 pages and could hardly be stapled. There was a telex in the editorial office, but no fax, no computers. We rattled the manuscripts into our Monika typewriters with three carbon copies. We spent the rest of the day playing "sink ships" in the editorial office.

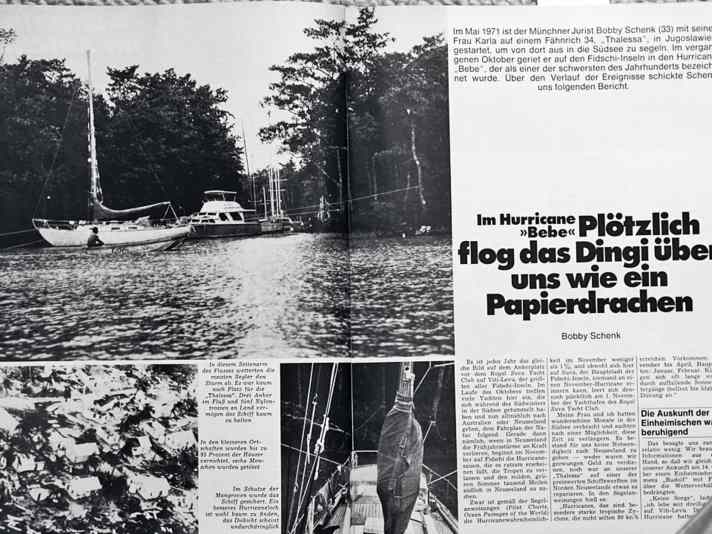

At that time, I received mail from a circumnavigator who reported on a typhoon experience in the Fiji Islands: a masterpiece! We met later at the Hamburg boat show, he was wearing a traditional jacket. The magistrate from Upper Bavaria would later become one of the most famous YACHT and bestselling authors: Bobby Schenk.

Horst Stern was and always remained my great role model. I accompanied him to the 1981 trial for the double murder on the ocean-going yacht "Appolonia"; he was the master, I was his pupil. We travelled to Bremen many times for the trial. Horst Stern regularly fell asleep in the courtroom, snoring audibly. It was very unpleasant for me. But the presiding judge was lenient with the famous reporter.

I owe what I learnt about journalism to the editor of YACHT. We remained friends until his death. Horst Stern was 97 years old. We buried him in 2019 in a small circle near Passau to the music of a Bavarian bagpiper. That was his wish.

I could write a book about my experiences at YACHT. About the interview with Éric Tabarly that I conducted in the shower with the otherwise inaccessible sea hero of the French in 1973. About my visit to the Royal Yacht Squadron, which opened its hallowed halls to a foreign reporter for the first time. About the conversations with Wilfried Erdmann. But in the end, the time with Horst Stern remains the most memorable for me.

Bobby Schenk, YACHT author

"You have sailed around the world, so your article will be printed!

How Bobby Schenk shook up old doctrines in YACHT and introduced thousands of sailors to the art of astronavigation

For this story, I need to expand a little. It begins in the late seventies, when my wife Karla and I are on our first circumnavigation. On the Marquesas Islands, we were waiting for a favourable departure time through the Tuamotus when an American asked me if I had a simple recipe for navigating with a sextant. He doesn't seem enthusiastic about my suggestion that he should just start with the total correction, i.e. the corrections for refraction, angular height, air pressure, etc.. "Total correction???", he asks sceptically. "Ah..., you mean 'plus ten'?"

That lights me up. The man simply saves himself the arithmetic by always adding ten minutes. Is that so wrong? Yes, but it's brilliant! Because with the usual eye level on yachts, the result, rounded up or down to the unimportant tenth of a mile, is actually only three values: ten, eleven or twelve minutes. If, for the sake of simplicity, you only ever add ten minutes, in the worst case you are off by two nautical miles. That's enough for practical purposes. You just need to know that astronomical navigation works without decimal places - and you can save yourself the total charge.

The "plus ten" idea electrifies me. Over time, I found a whole series of simplifications and wanted to publicise my method. So, at the beginning of the 1980s, I wrote an article for YACHT, which had previously printed many of my reports, saying that astronomical navigation could be learnt in a weekend.

Harald Schwarzlose refers me to the expert in the editorial department, Hans Georg Strepp. He, of course, rejects it outright - partly because I didn't use the "hexagesimal spelling". Strepp's letter, which Schwarzlose forwards to me, is remarkably short, not to say garbled. The editor-in-chief took the precaution of cutting out Strepp's unobjective remarks and gluing the pitiful remnants together with scotch tape.

At the boat show in Hamburg, he puts Strepp and me in a cubbyhole. We have a heated discussion until the boss decides: "You've sailed around the world using this method, so your article will be printed!" Hard to digest for Strepp, who until then had been YACHT's great navigation expert. Many people admired him, including me, for his sharp, occasionally acerbic writing.

So the article appeared. And it triggered a flood of positive letters from readers, the likes of which the editorial team had never received before. Encouraged, I offered the publisher a book entitled: "Astronavigation - without formulae, practical". The office manager, Mrs Steinbrinker, cautiously asked how many readers would really need this book. I said honestly: "Maybe 50." Delius Klasing nevertheless includes it in the programme preview. Shortly afterwards, there were already 5,000 pre-orders.

Hans Georg Strepp does not entirely accept the enormous demand unchallenged. He describes my simplified form of astronavigation as a "method for idiots". He is forgiven. The book is now in its 17th edition on the market and has attracted around 100,000 readers.

The dispute with Strepp is long gone. In the end, we got on very well. Because apart from his occasionally malicious writing, he was a likeable man. His publisher said that he was simply unrecognisable when he was sitting behind a typewriter. The last time we saw each other, he showed so much humour that he asked me, whom he had once dubbed a "Wilhelminian-style public prosecutor", to take a photo of us crossing our pens.