Weather: What will the summer be like? The forecast has become more difficult

Sebastian Wache

· 17.06.2024

Tell me, Sebastian, can you say what the summer will be like? Where should I go sailing this year?"

I am currently receiving countless questions like this, either on social media or directly on the jetty. At least on the latter, it's usually with a wink. People already know that a seasonal weather forecast is impossible.

Sure, I could claim that the individual months of summer will again be warmer than the climate average from 1961 to 1990, and I would be 99.9 per cent right. But that's easy now, because in recent years there have hardly been any months that have been cooler.

More articles on the subject of weather:

How the climate agent is created

To explain: for the climate mean, we take the temperatures, rainfall and hours of sunshine for the individual months over 30 years, average these values and assume them to be normal for individual locations. Based on these 30 years, we therefore know that in Rostock, for example, we can expect an average temperature of around 19 °C, 82 millimetres of precipitation and an average of ten hours of sunshine in July.

Rain and sun are so closely linked and so dependent on the weather that we can hardly make accurate forecasts for months in advance.

But with the temperatures, things are going uphill. Uninterrupted and still quite steep. Seen globally in the air, but also in the water.

There is no end in sight. And that presents us with major challenges. Especially in summer, when the air is hot and can get even hotter, this is a good breeding ground for severe storms.

Storms will come

In Central Europe, we always have to expect fronts, i.e. low pressure fronts, to cross us. If the air has warmed up beforehand, it can store more moisture. The warmer it gets globally, the more moisture evaporates from the oceans into the air.

This moisture is the energy carrier in the atmosphere. If more of it is present, this is noticeable in weather processes through larger amounts of rain and stronger gusts.

Rain may not bother sailors as much as someone on land who then has to pump out the cellar. However, the phenomenon described is interesting for him in terms of the stronger gusts. Stronger shower cells also have potentially stronger winds.

Typical weather conditions in summer

Whether in the harbour or on the road, these can quickly put a strain on people and equipment. Accompanying phenomena such as hail or thunderstorms should also not be underestimated.

Long-term forecasting of storms is difficult

However, such weather situations often occur at very short notice and therefore cannot be predicted in the long term. We meteorologists know relatively early on when severe weather is imminent. However, we can only see exactly where the showers and thunderstorms will form and where they will move to in the rain or thunderstorm radar on the day in question.

As a crew, you therefore have to sail by sight in such forecasts and choose your destination harbour so that you are safely moored before the storms arrive.

The general weather situation shows up early

The situation is different with the general weather situation and the jet stream. This shows how the weather will develop seven to ten days in advance. This is because it controls lows and fronts. This band of strong winds and its underlying air mass boundary serve as a separation between cold air in the north and warm air in the south, all year round.

If this line is now shifted northwards towards Scandinavia - for example, if the North Sea and the Baltic Sea are on the warm side of this air, a high can establish itself very well.

If the boundary has even been pushed over northern Scandinavia, the high over central Europe even has a connection to a Scandinavian high. This guarantees a very long-lasting and stable situation. We already saw this very impressively in May.

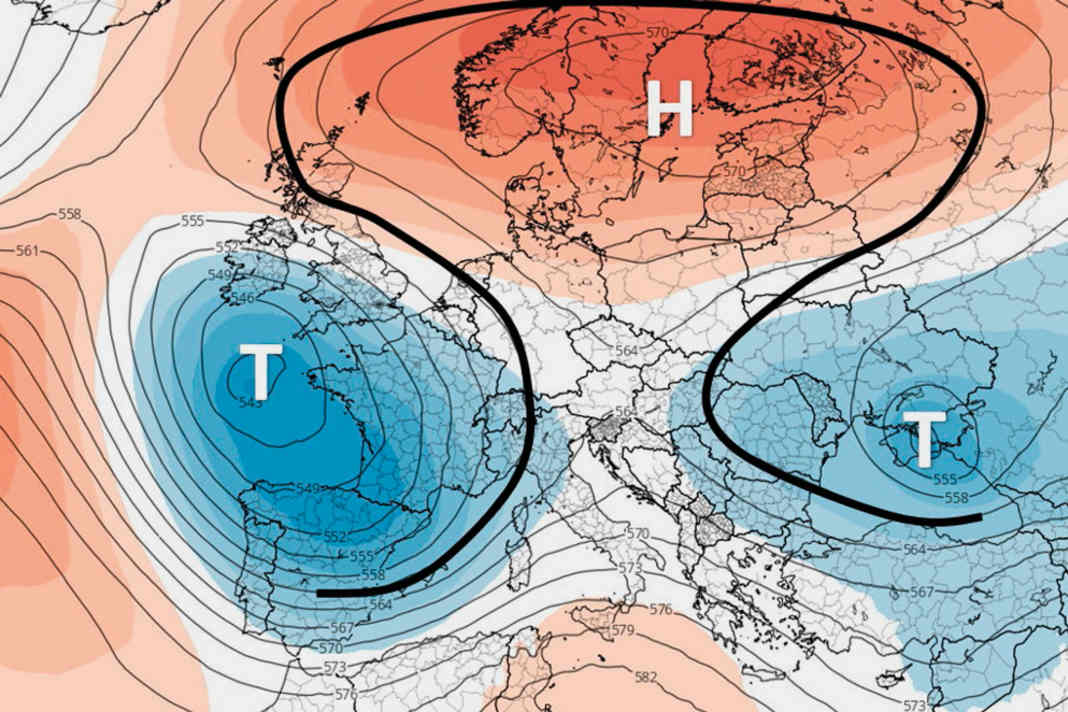

Particularly in the high-altitude current, you can see the large Greek letter omega on the weather map if you trace the course with a pencil, from which this typical omega high takes its name.

Low pressure systems are guided far around such an area of pressure, and those who are in its area of influence can expect plenty of sunshine, but usually very little wind.

However, this omega situation can also shift from time to time. If the high is only slightly pronounced, you continue to benefit from the sunshine, but also have quite good wind for sailing.

If, on the other hand, it lies over Great Britain or the Baltic States, it is only summery and sunny there. In this case, however, the sailing areas of the North Sea and Baltic Sea come to the edge of this high, where cold air from the north can flow into these more southerly areas.

Sudden changes

However, as the water is often already warm by then and the sun also has a lot of power to heat up the land, this constellation often results in a situation in which cold mountain air lies above warm ground air.

These two air masses then suddenly exchange vertically. Heavy shower clouds and even thunderstorms with hail form. And this happens again and again until the blocking weather situation with the Omega High in the west or east moves away or dissipates.

We are seeing such stable highs, which do not move or only move very slowly, more and more often on the weather maps as the air masses are getting warmer globally.

This can even lead to such bizarre situations that so-called heat domes form. The hot air is trapped in place like a cheese bell, continues to heat up and an exchange of surrounding air masses is no longer possible. This is something that we have increasingly observed in the Mediterranean region - this is how the 48 degrees in Sardinia came about last summer.

The jet stream decreases

In our latitudes, the development of the high-altitude wind is the most important factor. And the strength of this jet stream decreases more and more frequently in summer.

The weaker high wind then tends to form waves in which stable highs can develop. And studies show that the weakening Gulf Stream also contributes to such blocking highs over Europe.

Weather conditions are therefore becoming more stable to a certain extent and therefore easier to predict, but of course it depends on which wave of the high-altitude wind band you find yourself in.

Just think back to last year. From April to the beginning of July, there were constant highs over Europe for a good twelve weeks. The fear was that we might have to expect further highs and a massive drought until late autumn, just like in 2018.

However, after the dry phase, July and August then completely fell through, including a storm during the ORC World Championships. Suddenly we were on the other side of the high. So we were caught in a kind of low-pressure motorway, on which the lows travelled like a string of pearls from Iceland and Norway over the North and Baltic Seas with plenty of rain and wind.

And once you are caught in the low-pressure conditions, there are hardly any weather windows left to be able to make plenty of nautical miles. If, on the other hand, you are caught in the middle of the high pressure, there is often no suitable sailing wind despite the best weather.

The weather has changed

In principle, the following now applies: There are hardly any highs and lows that alternate regularly. It's no wonder that many people summarise after the season that there was either too little or too much wind during the time they were out.

Once again this year, we are seeing stable Omega highs that will determine our pan-European weather over longer periods. And even if all these findings can give us a picture of the upcoming summer, nobody knows in detail what exactly the sailing summer will bring us.

Especially not in the only two or three weeks of sailing that you might have time for during the holidays.

However, a summer like this is long and the entire sailing season is a bit longer, so we can still expect plenty of perfect sailing days. In any case, I'm keeping my fingers crossed for everyone to find the right winds at the right time. And if there are any uncertainties about the weather conditions, there is always the option of asking someone who knows about them.