Technology special: Travelling with twin rudders: what you need to know

In the past, twin rudders were seen almost exclusively on certain regatta yachts or other special designs, but now they can also be found in series production. From sporty small yachts such as Seascape or SQ 25 about entry-level cruising yachts such as Dufour 310 or Elan 350 up to flagships like Bavaria Cuiser 56 the range extends. Two rudder blades can have significant advantages over one - and huge disadvantages. Their use depends on many factors. They require a slightly different understanding of the physics of sailing and a new way of thinking when operating the yacht, whether at sea or in the harbour.

Among the pioneers of twin rudder systems are the ocean-going boats of the Open 60 class. These are space-sheet gliders with flat, wide sterns. The wider the stern, the greater the advantage of a twin rudder. This also applies to cruising yachts. Today, they also have enormously wide stern sections, but more for the reason of creating plenty of living space on and below deck, rather than to help the yacht glide. And so the decision in favour of a twin rudder for cruising yachts has somewhat different reasons than for racing yachts.

The physics behind the two rudder models

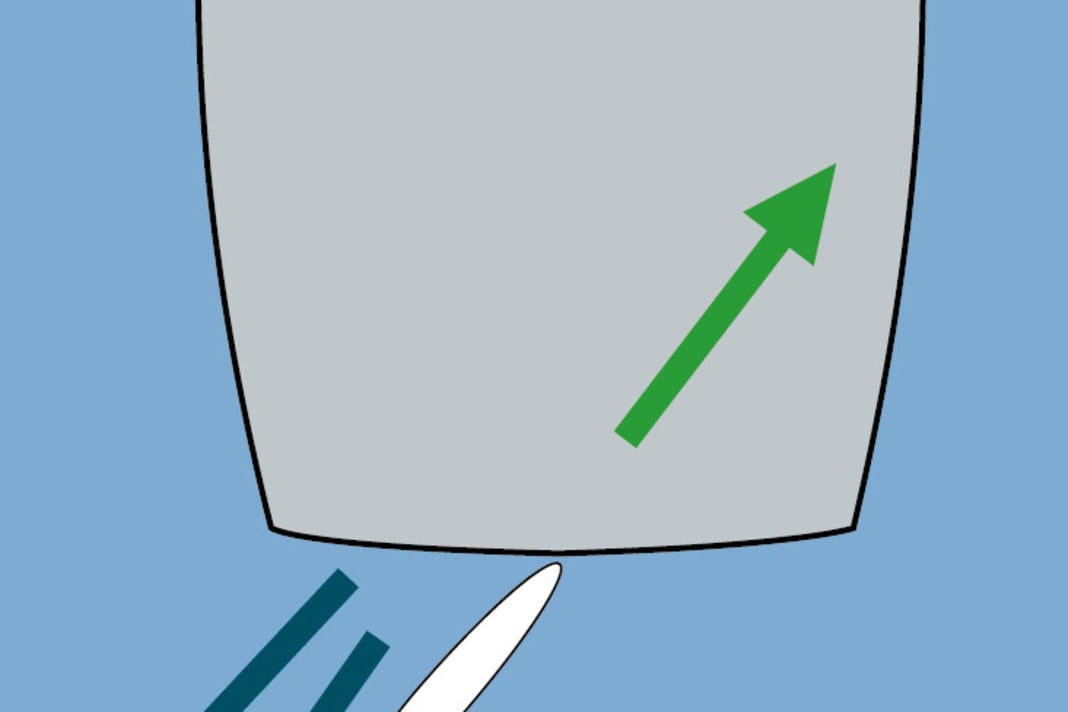

The angle and surface area with which a rudder glides through the water changes depending on the heel. These are the two core problems that you need to be aware of if you want to make statements about the advantages and disadvantages of rudder systems.

Firstly, consider the upwind course: A rudder is generally most effective the further aft it is on the hull; among other things, the course keeping ability then improves. However, the wider a yacht is, especially aft, the more it will trim when heeling. The flat shape of the bulkhead lifts the windward side out of the water and, to put it simply, the yacht falls on its nose. Trimming is accompanied by strong windward yaw, to which the helmsman must react with a significant rudder deflection. This creates large pressure differences around the rudder blade. Trimming to the nose also has the effect of levering the stern upwards. This means that a single rudder installed amidships in the upper section - the further aft it is, the more likely it is to dive out of the water.

To put it bluntly, this means that there is no lid on the system. The negative pressure on the rudder can find an equaliser by sucking in air from above. This results in a stall and loss of control.

An alternative is a correspondingly large and, above all, deep rudder blade. Most designers today resort to this variant. What seems surprising at first is that there is an apparently much better option: the twin rudder. On the contrary, it becomes all the more effective the further the yacht heels, as it is then completely submerged. Boats with a twin rudder can normally still be kept on course very well, even when they are heeled over heavily and other yachts are already producing sunshots. The enormous gain in control provided by a twin rudder is so pronounced that one involuntarily wonders why not all modern, wide cruising yachts are equipped in this way. "A twin rudder also means twice as many opportunities to do something wrong," says Matthias Bröker, designer at Judel/Vrolijk & Co in Bremerhaven.

When is a twin rudder worthwhile on standard yachts?

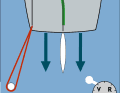

A yacht is not swept parallel to the current, but around it. The further away the current is from the centre line, the more it is deflected. In order to be correctly positioned in the current, the rudder to leeward would therefore have to be at a different angle to the rudder to windward. However, this would increase the resistance. Another effect is the fluttering of the windward rudder, which occurs when it dips only slightly. The solution to this is again a slight lead. How negatively these effects can add up is shown by the comparison between the Dufour 310 and the Beneteau Oceanis 31.

The leaves of the Dufour 310 still have around 30 per cent less wetted surface area together than a single rudder would have on this boat, according to their Italian designer Umberto Felci. Nevertheless, and this is a very important aspect, the twin rudders only have an advantage when the windward rudder is flying, i.e. protruding out of the water. This is why Felci has kept the blades so short that this effect occurs from 25 degrees upwards. With little wind or courses lower than half wind, however, such a heel is rather rare. This already shows how narrow the range is in cruising sailing in which a twin rudder can gain an advantage in terms of speed. The situation is completely different in racing. In the Open 60s mentioned above, the rudders can be folded up individually thanks to sophisticated mechanisms. This eliminates the negative effects and achieves a significant speed advantage. Under such conditions, a twin rudder makes perfect sense.

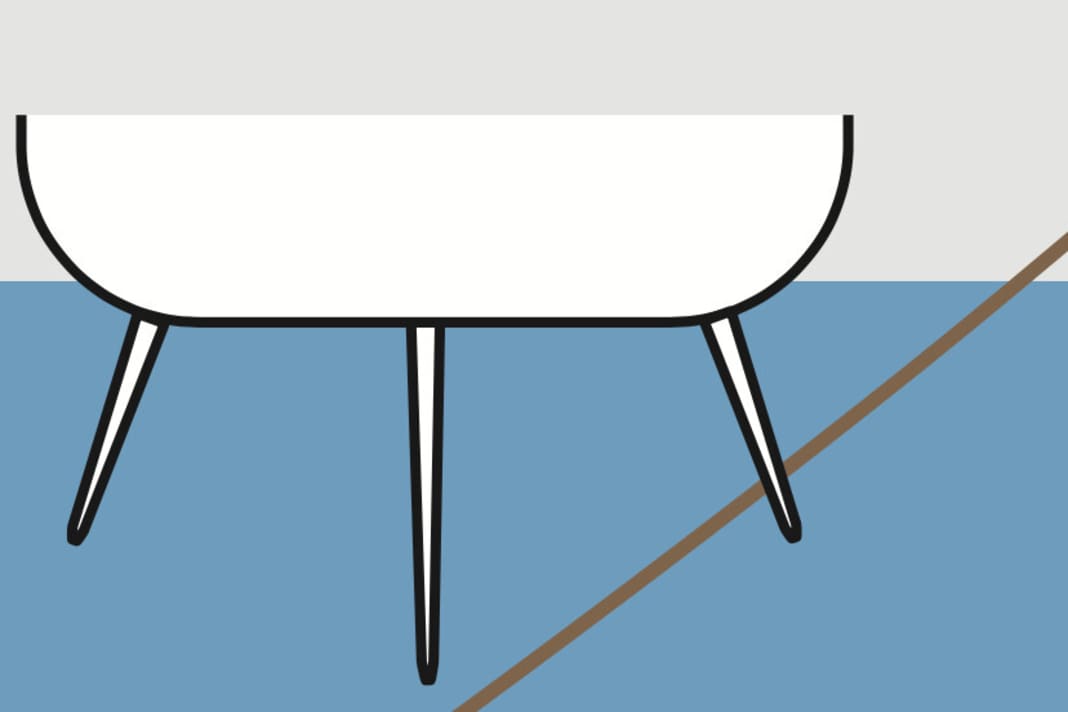

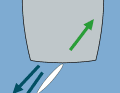

Both rudder systems have their advantages and disadvantages. The single blade is more universally applicable, double blades are used more in specialised areas. A brief comparison in pictures:

When cruising, the advantages lie in other areas besides better control. For example, a twin rudder significantly reduces the draught, which, in conjunction with a suitable keel, makes the yacht suitable for shallower waters. Designed accordingly, the two blades are also suitable as wading props, and such a yacht can be sailed upright and dry. In addition, twin rudder systems keep the stern free of an axle in the centre, which is also used as a dinghy garage on larger yachts. It is debatable whether a twin rudder on a cruising yacht represents a safety gain. Although a single rudder blade is better protected from collisions by the keel than two exposed single blades, two blades can form a kind of redundancy system. However, this is only possible if the steering system is designed with redundancy.

Manoeuvring behaviour and inflow

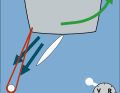

It is assumed that the manoeuvring behaviour in confined spaces with twin rudders is significantly worse due to the changed position, the flow caused by the propeller thrust and the short length of the blades. However, this is only partially true.

We have described the common manoeuvres with a Dufour 310 and the SQ 25 (both with twin rudders) and noticed an astonishing manoeuvrability. This is astonishing because a double rudder system eliminates a very important effect: the direct flow of the propeller jet onto the rudder blade. With single blades, this makes it possible to generate turning impulses from a standing start. However, as yachts with twin rudders are usually modern, manoeuvrable designs with short keels, this shortcoming is largely compensated for. With both yachts, it is possible to sail just as tight circles at low speed as with a single rudder. Nevertheless, some manoeuvres lack initial impetus, for example when casting off alongside with a stern line laid out aft on the outside of the stern. This manoeuvre works surprisingly well on most yachts with a single rudder. With a double rudder system, however, the important pressure on the blade is missing.

However, if you pay attention to this behaviour, you will hardly have any problems. Since a twin rudder system does not have any serious disadvantages in harbour either, its use in the cruising area is only a question of the exact definition of the requirement profile and the price. If in doubt, sacrifice some speed in favour of better steering behaviour downwind.

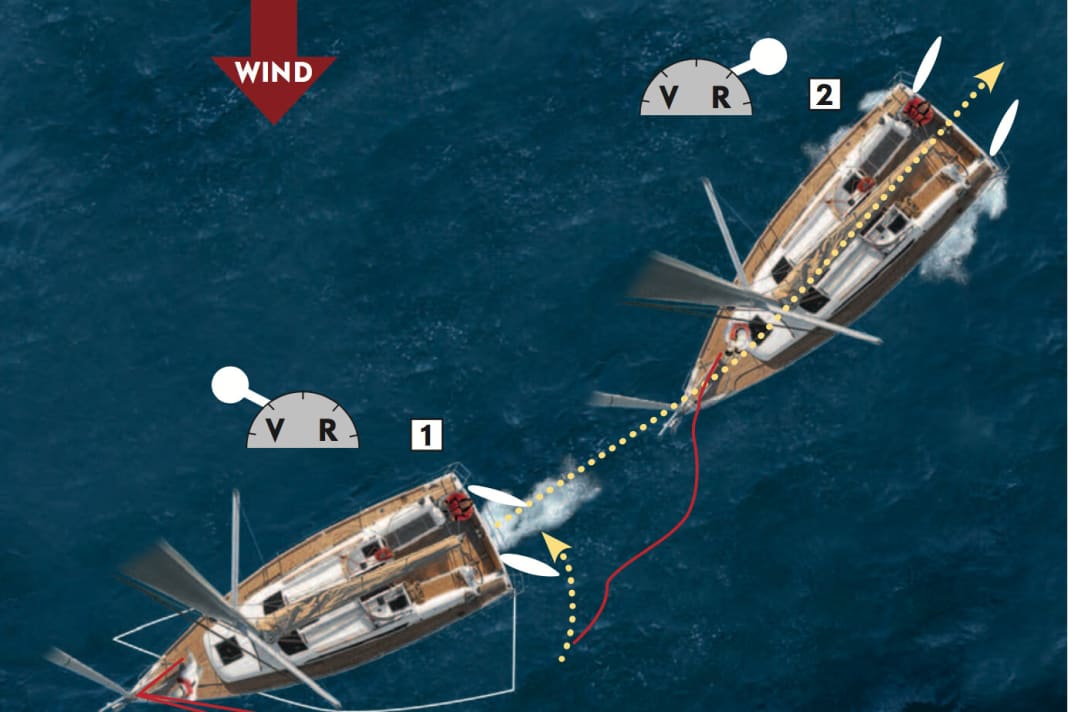

Manoeuvring tips in pictures

While the flow to the rudders is not as ideal as with a single rudder due to the propeller thrust, the wide sterns, which double rudder yachts generally have, are particularly helpful when manoeuvring. Relaxed mooring and casting off, even with a small crew, is best achieved with the aid of lines.

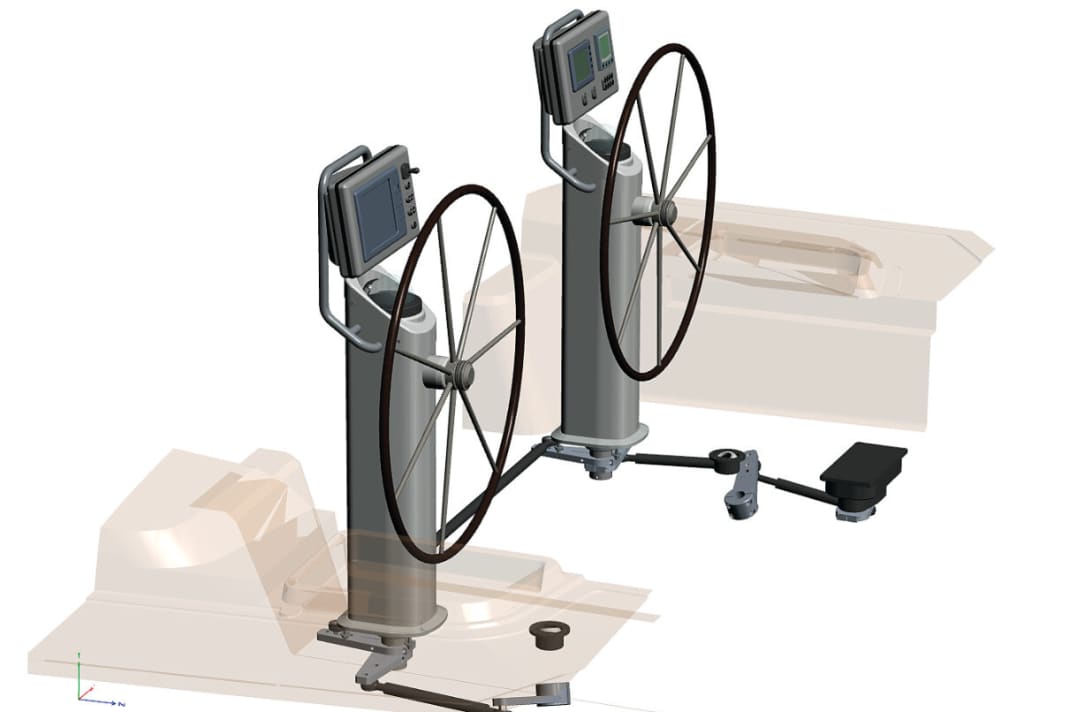

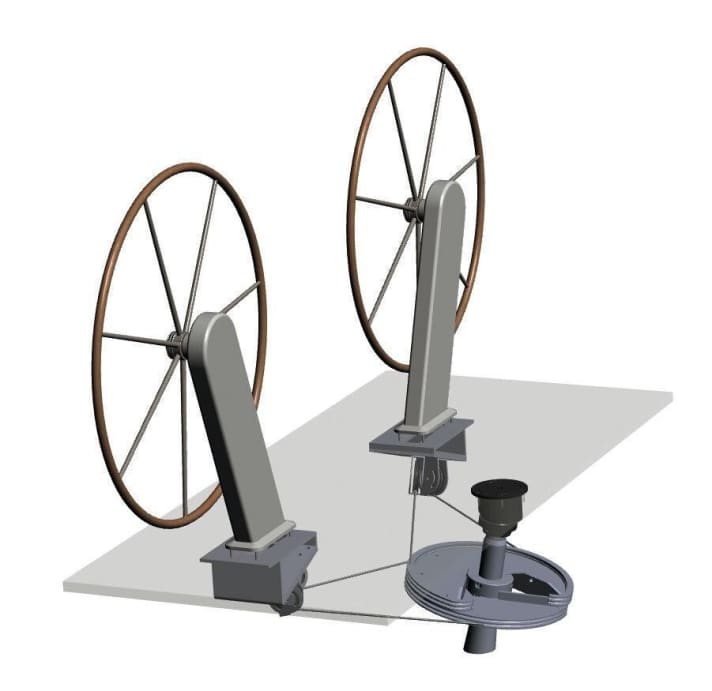

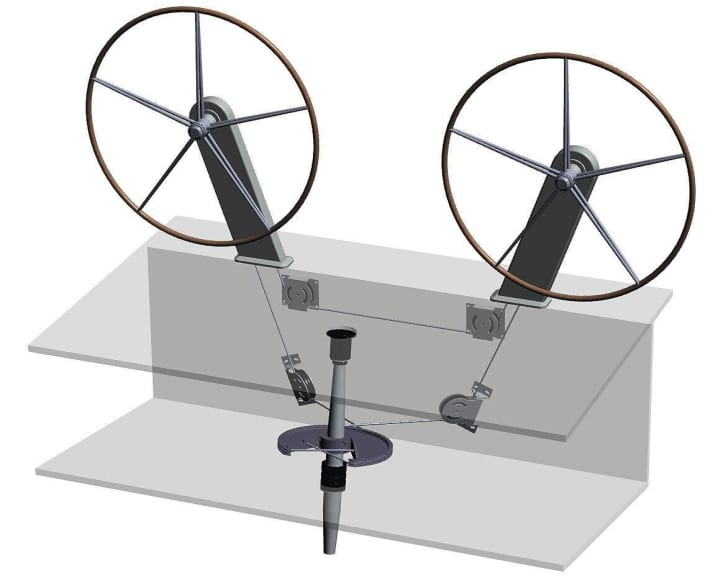

These types of steering gear are available - and how they work

Three main systems are used today to transmit the forces from the steering gear to the steering gear. They can also be combined very variably. An overview:

For cost reasons, wire systems are generally installed on standard yachts. There are systems with a single or double control cable. Which variant is safer, which is more expensive?

Double control cables

Good: Each wheel has its own steering cable. Although this means double the work when tensioning, it also guarantees that the other wheel can continue to be steered in the event of a material breakage in the sensitive ropes. The redundant system is somewhat more expensive to manufacture as it requires more installation work and a more complex quadrant with two guide grooves. The shorter distances and therefore shorter ropes mean less stretching and therefore less maintenance. And an emergency tiller becomes obsolete.

A control cable

More susceptible: A single, sometimes very long steel cable must transmit the steering commands from each of the two wheels to the quadrant. To do this, it must be under high tension in order to cover the usually long distances between the deflection points without slack. Too much slack on the cable harbours the risk of it jumping off the pulley during violent steering movements. The system then often jams completely, and even the emergency tiller no longer helps.

Lars Bolle

Chief Editor Digital