On the vast majority of sailing yachts, the day begins and ends under engine power. But this can be cancelled. Dinghies don't have one in the first place, the crews of smaller keelboats leave the outboard motor on the jetty when racing, and even some of the 20-metre-long twelve-wheelers are not even equipped with a drive by their ambitious owners for performance reasons.

But when a normal cruising yacht sails into the harbour without an engine, everyone jumps up as if an episode of harbour cinema is about to begin, the unpleasant outcome of which is predictable. Many people cannot imagine that this is a deliberate manoeuvre.

This also explains radio messages asking for towing assistance due to engine failure. Because of engine failure? What's wrong with the sails? Is it really that complicated to moor and unmoor a medium-sized cruising yacht without engine assistance?

The answer is yes and no.

If the crew is caught cold by such a scenario and has never practised such manoeuvres, this can cause grey hair in combination with unfavourable weather conditions. Those of us who practise such manoeuvres for safety reasons, simply for the sake of it or even to earn a few approving glances in the next harbour, on the other hand, are unperturbed by an engine failure.

The principles to be followed when sailing the typical harbour manoeuvres are explained below. This should ensure that even those who have not yet familiarised themselves with the subject will be able to complete the exercise.

Cast off alongside the jetty

Casting off is often easier than mooring and alongside is easier than out of the box. If the boat is not too close to the jetty or quay wall and the bow is pointing into the wind, you should definitely not miss the opportunity to cast off under sail for the first time. With wind from the front and plenty of slack in the sheets, both foresail and mainsail can be set without the boat wanting to move immediately.

Once the sails are up, the lines are cast off. The last mooring line is the stern spring, which is lying on a slip. Now all you need to do is lower the foredeck to allow the ship, which is well fendered at the stern, to fold away from the jetty. The sheets are then tightened and the stern spring is hauled in.

It would be a good exercise to always deal with such simple situations in this way. After all, it builds confidence for the more difficult tasks. For those who still find this too nerve-wracking, we recommend simply letting the jockey wheel run along disengaged. This creates mental security and has no influence on the learning effect of the manoeuvre.

Depositing from the box

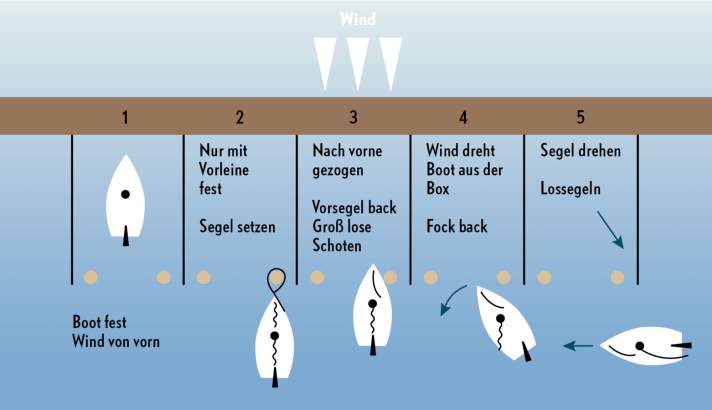

This is also no problem as long as the boat is lying in the box with the bow in the wind. The aft lines are hauled in, the fore lines are slipped and fished until one of them can be tied to one of the aft dolphins. The boat now hangs on a fore line and aligns itself precisely to the wind. Ideally, you should hang on the starboard dolphin if you want to sail away to port later, and vice versa.

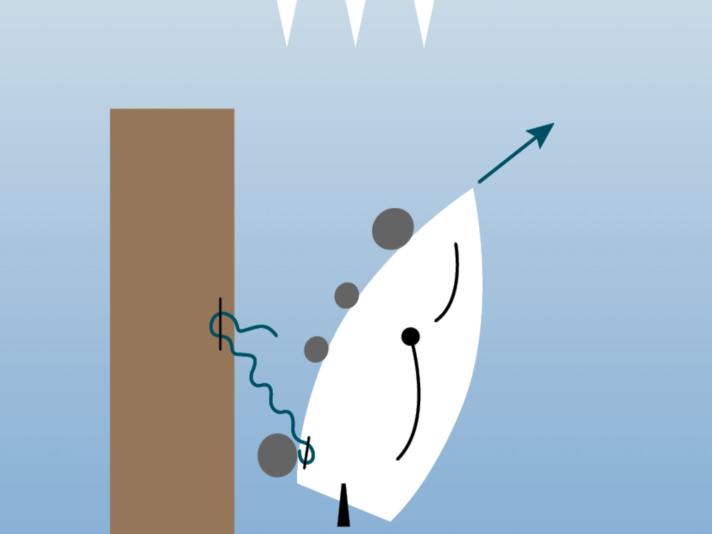

In this situation, the sails are again set with plenty of slack in the sheets. The jib is to be set back later for sailing away, so the sheets are already set accordingly. The mainsheet remains loose for the time being. If you now want to sail to port out of the pit lane, pull the boat forwards on the slip line until the dolphin is on the starboard side of the bow.

Now haul in the fore line and push the bow boldly off the starboard pole to port. With the foresail standing astern, the ship will turn more or less on the spot to port, but will not move forwards. If the pit lane is in front of the bow, the jib is overhauled, the mainsail is tightened and the boat sails out of the lane with half the wind.

The critical point is the moment when the boat is pushed off the dolphin. The aim is to generate a turning movement, not to sail back into the box or even into the neighbouring box. If a boat is moored there, the appreciative glances of the neighbours will quickly disappear. For this reason, the person pushing the boat off at the front remains in this position until it is clear that you are really free of further poles and can sail through the lane ahead.

Casting off under sail results in safety gains and time advantages

This type of filing has many advantages. All the work is done while you are still moored. Fenders, lines and life jackets - everything is ready to sail when you leave the harbour. Single-handed sailors in particular benefit from this fact. Nobody has to fiddle around on the boat when it is moving, not even an autopilot is required. This results not only in a safety gain, but also a time advantage.

If the wind direction does not match the planned layline, it makes sense to move the yacht to another dolphin or a jetty with an offshore wind. From there, the manoeuvre is then carried out as described. If there is actually no engine available because it is not present or defective, such a shifting manoeuvre can be a greater challenge than the actual casting off. If the boat is moored in a box with wind from aft, for example, you can try to put the boat in front of the piles, if a crew is available, and then push it alongside to accelerate it. Once the boat is under way and the rudder is working, the headsail is set and the boat is sailed off.

Wind, currents and, above all, ideas and creativity make the seemingly impossible possible

However, if the yacht is too heavy for such a manoeuvre or the crew is too small, this manoeuvre is unsuitable. In this case, a line to the opposite side of the pit lane will help. This can be used to move the boat to the other side, where you then have the ideal conditions described at the beginning.

When it comes to getting the line across the wide pit lane, creativity is definitely required. If the water is warm, swimming may be suitable; if it is cooler, a SUP or dinghy can be used. If none of these are available, simply take advantage of the wind and throw the line tied to a fender from the opposite jetty into the water. Now you just have to wait until it has drifted over and can be fished out with a boat hook.

Casting off under sail therefore always means getting the boat into a suitable position first, which is sometimes challenging and can be much more time-consuming than the casting off manoeuvre itself. With the support of lines, wind, current and, above all, ideas and creativity, what seemed impossible becomes possible. And last but not least, it's a lot of fun.

Entering the harbour

It is much more challenging to find a berth in the harbour under sail. The prerequisite for a successful manoeuvre is the ability to bring the boat to a halt without using the engine as a brake, preferably with pinpoint accuracy. Different boats may react very differently to the aforementioned manoeuvres. A heavy, deep-draught long keel boat behaves completely differently when stopping than a modern boat with a shallow underwater hull and short keel. It is therefore important to find out exactly which strategy works for your own boat. This, in turn, is not possible in every harbour. In some places it is undesirable, in others it is a welcome change from the daily harbour cinema.

Therefore, the first step is to practise a controlled uphaul. The aim is to develop a good feeling for how far the boat will drift with loose sheets or even just in front of the top and rigging. Above all, the wind, from the front, from behind or from the side, makes the manoeuvre look different every time. Before the first motorless mooring, it is advisable to practise the shooting manoeuvre with little wind and current. Experts in MOB manoeuvres are already experienced and therefore have an advantage, but these manoeuvres typically take place in the open sea. When mooring under sail, on the other hand, there is only limited space available in the harbour, which is usually quite narrow.

Spontaneous rethinking and quick reactions often required

A successful push-off is when the yacht has lost speed at the desired point. If, on the other hand, you come too short or too far, strategies must be found to counter the problem. If the boat is travelling too fast, for example, S-turns can help to extend the remaining distance and generate additional time. The rudder, which is alternately and jerkily turned to port and starboard, allows the current to break away and thus acts as an effective brake. If the wind comes from the front, the boat can be stopped with the mainsail held back as a huge drag. The jib thrown overboard, tied to the long stay on one of the aft cleats, also acts as a drift anchor and is therefore an effective means of slowing the boat down.

When passing a row of piles, a line can be used to take speed out of the boat. However, the high residual energy that even a slow boat still has must be taken into account. The line is therefore not run out of the hand, but over a cleat.

A completely different situation arises if the speed is lost before the destination is reached. With smaller boats, you can help yourself by using a rudder or oars to wriggle. Or you can use a paddle. With larger boats, however, which displace several tonnes, this will not get you any further. Help from ashore is a real asset in such situations. A crew member equipped with a throwing line can try to establish a connection to the jetty or the neighbouring berth.

Mooring at the jetty

The first real manoeuvre follows the uphaul. As with the casting off manoeuvre, a free jetty with the wind parallel to it is ideal. If, for example, the conditions require mooring on the port side, the boat is prepared as follows: All existing fenders are deployed on the port side. At least two really large ball fenders are very helpful here, which are attached about halfway between the centre of the boat and the ends. A line is then attached to the centre cleat and laid ready for casting. A leader line is also attached and made ready for use. If the conditions are such that the boat can run a few degrees upwind with just the headsail in case of doubt, the mainsail can be dispensed with. One less cloth to work with creates additional free capacity.

Here we go. To be on the safe side, the engine can chug along at idle during an exercise, but this is really not necessary for this manoeuvre. What's more, the sense of achievement is much greater if you can sneak up to the bridge as quiet as a mouse. You approach the jetty at a fairly obtuse angle of around 70 to 80 degrees, i.e. with almost half the wind. The speed is controlled with the jib sheet. It is now the throttle. If it is eased, this means less propulsion. If it is furled further until the jib is completely blown out, it will eventually have no propulsion at all. If you tighten the sheet, the boat will pick up speed again.

No fear of a second attempt

In this way, the boat approaches the jetty as quickly as necessary for the rudder action, but as slowly as possible. Two to three metres from the jetty, the sheet is cast off completely with minimal remaining speed and the rudder is set so that the boat is parallel to the jetty. Ideally, you should come to a halt with the centre cleat at the height of a bollard on the jetty. Then just put an eye over it, close up the mooring line, tie it up and you are secure for the time being. The combination of a very short mooring line in the centre of the boat and two large ball fenders to the left and right of it prevent the boat from coming into contact with the bow or stern.

If the manoeuvre fails because you are going too fast, simply steer away from the jetty again, tighten the jib to starboard and off you go for a second attempt. If you are too slow during the approach, which rarely happens in the situation described, the bow will fold to port. In this case, you can move away from the jetty after a jibe and prepare for a new approach. This docking manoeuvre should be practised again and again, as it prepares you perfectly for everyone else and builds self-confidence.

Creating in the box

The next step up, and here it is advisable to keep the engine running at the beginning, is sailing into the box. Of course, you practise this in your home harbour first. Here you are familiar with the conditions and know that your own box is free. The ideal situation for practising is when the pit lane is not too narrow and there are safety lines stretched from the dolphins to the jetty in the pits. The wind should be light and from a direction that makes it possible to moor with a light aft wind.

The ship is prepared as if it were being moored under engine power. Two forelines are laid on the forward cleats and are neatly shot out ready for casting. There are also two stern lines, each with a large bowline eye to lay them over the stern posts. Two large ball fenders hang on the port and starboard side of the bow. As the boat is very narrow here, they do not get in the way when passing the dolphins. Should the boat drift towards the neighbouring berth, they prevent damage. All other fenders are tied to the sea railing, but are still on deck so that they can be deployed if necessary.

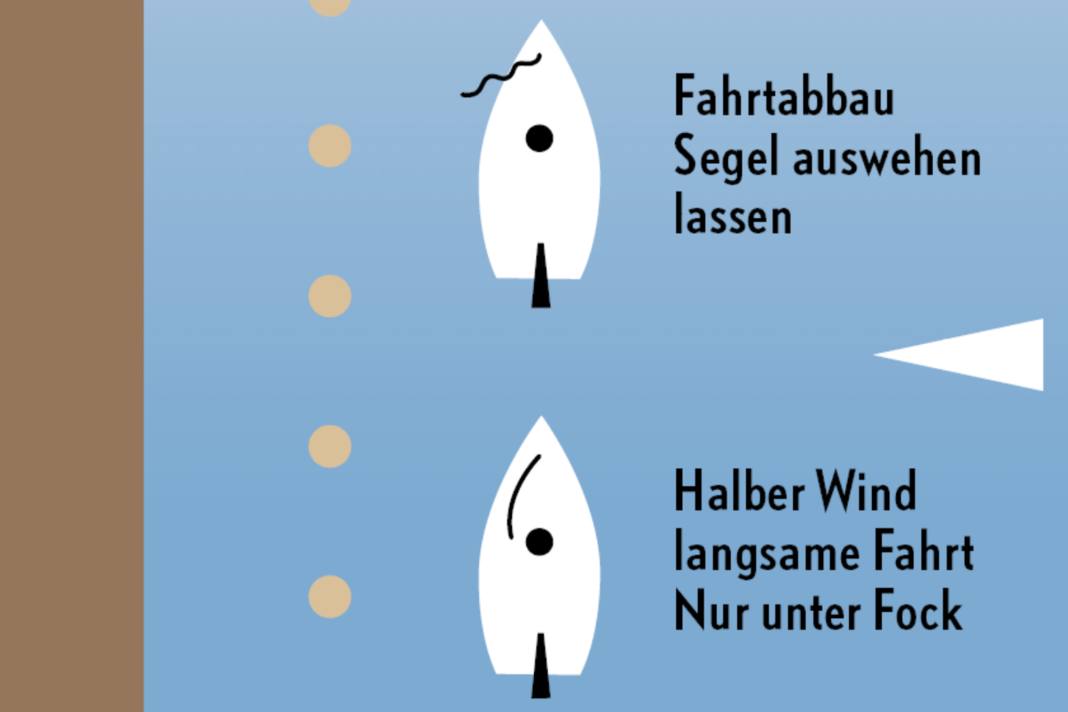

If space permits, the manoeuvre is started in a clear extension of the pit lane. You can then have a full view of it before you enter. If another boat is getting ready to leave, one or two more waiting laps are made to avoid critical encounters in narrow places. The speed should be reduced in good time. If this does not work, you can abort the manoeuvre before entering the pit lane.

Only the foresail is used in aft winds

Similar to mooring alongside, the speed is reduced to an absolute minimum by letting out the headsail. Ideally, you should remain almost stationary in a position almost abeam of the box you want to enter. If you now take the headsail back, the bow turns into the box. During this turn, the jib drops or is furled. The wind does the rest. It is important, however, that at least one of the aft mooring lines must be laid over a pole, as this allows the boat to be stopped in front of the jetty.

All manoeuvres that end with a stern wind should only be carried out with a headsail. The more aft the wind is, the worse the mainsail falls and, due to its design, it cannot be blown forwards. In the case described above, the boat would accelerate in the box, and that is something to be avoided. It would be different if you had to shoot up into the box. Especially if the wind is so weak that there is a risk of starving to death in the lane, you are welcome to sail with a main.

And this is exactly what it comes down to: analysing the respective situation and correctly assessing what will happen where. In addition to practical practice, this is the key to success. Of course, this consideration may also reveal that it is impossible to enter the harbour under sail in the prevailing conditions. A plan B is needed for such cases.

Plan B: Have an anchor ready

All vessels covered by this article should have an anchor on board. You can often anchor in the lee of a harbour or, even better, in the outer harbour. There you can wait for conditions to improve or make use of towing assistance, perhaps even that of your own dinghy. The motorless twelve-wheelers mentioned at the beginning do the same if the conditions do not allow a harbour manoeuvre under sail. One thing should be explicitly stated at this point - it is not bad seamanship to call on outside help in such situations. On the contrary, if there are fears of putting yourself, others or the boat in danger during a manoeuvre, outside help is actually the method of choice.

For those who study the subject of harbour manoeuvres under sail in more detail in the future, an engine failure should soon no longer be an emergency. At best, it will even be accepted as a sporting challenge to bring the boat safely into harbour. Once you have successfully completed the manoeuvre, a crew will always be proud - and rightly so.