- The oldies surprise with their sea friendliness

- The concepts of the three candidates

- The behaviour of the modern yacht in rough seas

- The behaviour of the oldies in rough seas

- What is sea friendliness anyway?

- Why do modern yachts perform so poorly?

- Length runs - is that true?

- What influence do the shape of the keel and rudder have?

- The picture changes on the space sheet

- The comparison in the video

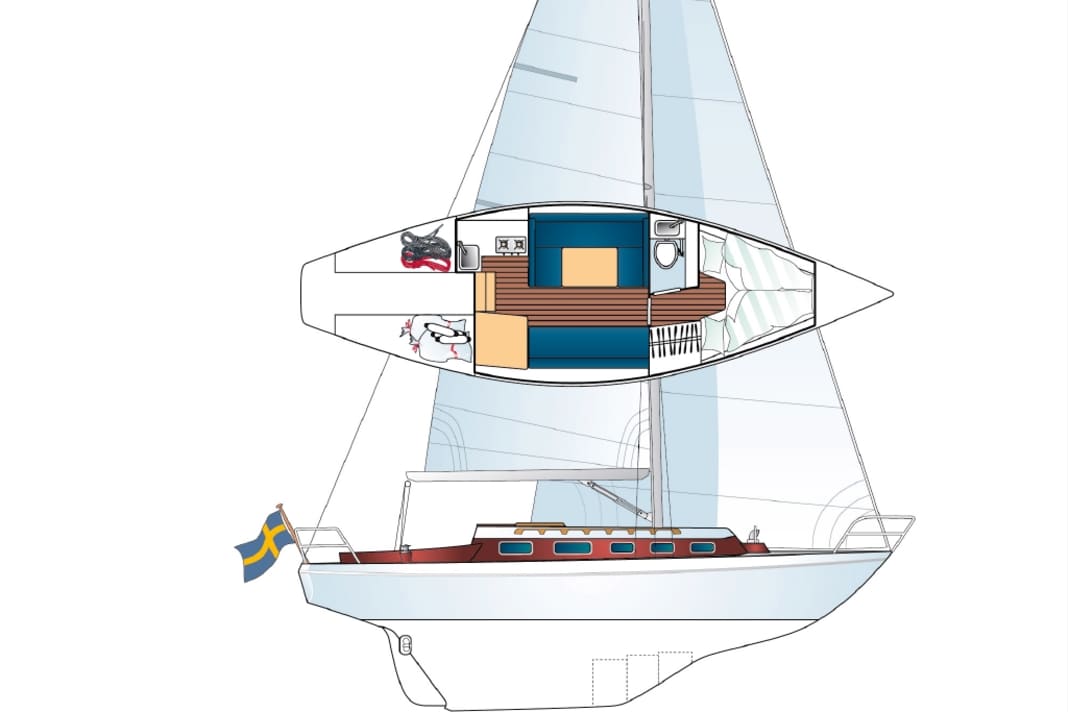

There is a clear winner. Each of the six testers opted for the same yacht. Regardless of whether they are regatta, dinghy or cruising sailors, the vote is clear. There are three candidates to choose from: a Vindö 40, a Hallberg-Rassy 29 and a Sun Odyssey 30i. All three are roughly the same length and were considered successful cruising yachts in their day - although they differ significantly in design.

The question: Which yacht sails best in a hard Baltic Sea wave? When the sea is steep and short, as is often the case near the coast. When yachts under twelve metres in length like to get stuck, when it gets uncomfortable. Which is the better hull concept then: short keel, long keel or a moderate mix of both? Whereby the keel is not the only decisive criterion, it is more about the associated hull shape. The ideal area for this is the western part of the Fehmarn Sound between Fehmarn and the mainland off Heiligenhafen. The day before there was a storm from the west, now it is still blowing at around 5 Beaufort. The old wave rises about one to one and a half metres in the rising ground, the distance from crest to crest is about ten to eleven metres. Occasional foam crests, sometimes a moderate breaker. All in all, very uncomfortable conditions, hack, as they say.

The oldies surprise with their sea friendliness

The first impression is an aha experience. The older ladies are a match for the supposed young dynamic, and even more: the Hallberg 29 sails higher and faster, the Vindö 40 on a par with the Sun Odyssey. However, the main criterion of the comparison is comfort, the behaviour of the yacht in rough seas, not the top speed. This sea friendliness is one of the most important reasons for seasickness, for going sailing even with more wind and waves - or not. To anticipate this: Both "old-timers" also performed better than the modern boat in this important category.

How can that be? Three to four decades of boatbuilding, research and development lie between the Sun Odyssey, which was designed in 2008, and the other two yachts. During this time, a complete rethink took place among the designers, as a closer look at the three candidates shows. However, this rethink has obviously not always led to the better.

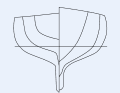

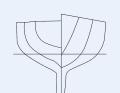

The concepts of the three candidates

The Vindö 40 is a classic long keeler, designed in 1971, with the main bulkhead in the shape of a wine glass. The Hallberg-Rassy 29 can be seen as a transition to today's design philosophy. It was designed in 1981 as a so-called moderate long keeler, with a separate lateral plan, the rudder separated from the keel, with a skeg. The frame shape is somewhat sharper, more V-shaped at the front. The keel itself is still relatively long in relation to the draught. The Sun Odyssey 30i represents a stark change in the design concept. Its main bulkhead is U-shaped, dinghy-like, it has a lot of freeboard, but remains flat below the waterline. The rudder and keel are arranged separately from each other and are very narrow, as well as being bluntly attached to the hull without a harmonious transition. She is a typical representative of today's large-series yachts in this category, comparable in her basic concept and in the ratios of length to width, sail area to weight or ballast to displacement with the entry-level models of other shipyards such as Bavaria or Beneteau.

The behaviour of the modern yacht in rough seas

The behaviour of the ships in rough seas is as different as the concepts. In a nutshell: the modern yacht disappoints. At the start, all three boats lie parallel to each other on an upwind course. They head to windward for about a nautical mile, then back to windward, the helmsmen change yachts, then a new approach. The picture remains the same. The Sun Odyssey is behaving wildly. She makes jerky movements in all directions. Heeling heavily, then sailing upright again. Runs with the bow, levering out the stern, sometimes luffing uncontrollably into the wind. When the bow breaks through a wave, the foresail crashes into the wave trough shortly afterwards. The first reef is inserted into the mainsail. With the second, the movements were somewhat more comfortable, but there was a lack of pressure in the acceleration phase.

The crew has to decide who should work, because work is necessary. Either the mainsheet is used, in which case the helmsman has to turn the wheel a lot. So much that it can only be done standing up, sitting upwind there is no grip. Alternatively, the second crew member can take the mainsheet out of his hand to regulate the pressure. Although this is a relief for the helmsman, it is extremely strenuous for the co-sailor. In addition, the wide, open cockpit offers little opportunity to lean to leeward, but plenty of room to fall in that direction. All in all, it is more of a fight against nature than with it, very uncomfortable, very tiring.

The Sun Odyssey is comparable to a buggy that jumps from hill to hill, taking every pothole in its stride.

The sea behaviour of all three test candidates

The behaviour of the oldies in rough seas

The two older yachts sail quite differently. The Vindö pushes through the mountain in front of the bow like a bulldozer. A large wave is displaced to leeward. The long keeler holds its course unimpressed, at most losing speed slightly. The rolling movements are much smaller and gentler than on a modern yacht. All reactions are rather sluggish, giving the impression of not really being under way yet.

But the impression is deceptive: the Vindö can almost maintain the speed of the Sun Odyssey. The only annoying thing at first is the strong heel. As soon as the sails are pressurised, she leans about 20 degrees to leeward and dips down to the foot rail. This gives the impression that she has too little stability, but after a little familiarisation it becomes clear that she can hardly be made to heel more than 30 degrees. She carries the full genoa 1, the main is reefed once. The keel, which weighs almost two tonnes, has a ballast ratio of around 40 percent

The Hallberg-Rassy performs best on the Amwind course. Like a heavy off-road vehicle, it absorbs minor bumps and takes larger bumps in its stride. From the outside, it sometimes looks very impressive when the bow rises steeply upwards, she seems to jump over the wave up to her keel and lands in a fountain of spray. On board, however, the experience is far less spectacular. Due to the seating position far aft in the cockpit, the crew only feels the vertical movement of the bow to a much lesser extent. In addition, the hull gently enters the wave trough and the fountains of spray are caused by the foaming water being displaced sideways. The HR doesn't produce the kind of bang that the modern U-frame hull of the Sun Odyssey reliably produces.

What is sea friendliness anyway?

How can it be that the more modern hull does not perform significantly better, both in terms of feel and objectively, and is not significantly more seaworthy? "Seaworthiness is the ability of a boat to absorb the forces of a rough sea and transfer them into movements that are compatible for people and property," defines the researcher and engineer C. A. Marchaj in his work "Seaworthiness - the forgotten factor". In it, he examines the behaviour of different constructions in rough seas.

Today, however, seaworthiness is only one of many requirements for a series-produced yacht. More than its predecessors, it must also offer living space, comfort in harbour and at anchor. Standing height below deck is a matter of course for a nine-metre yacht, as are double berths fore and aft, a fully-fledged saloon, galley and separate wet room with shower. There is also a large cockpit for sundowners with friends. This requires an enormous volume, which leads to compromises. The real achievement of the designers is that today's yachts are not significantly slower than their predecessors. However, measures that increase speed in smooth water and moderate conditions often result in the yacht reacting uncomfortably in rough seas.

Why do modern yachts perform so poorly?

This includes the U-frame. On the one hand, it reduces the wetted area and thus the drag, and also gives the hull greater dimensional stability than the S-frame. This means that less ballast is possible.

Modern U-frame ships with a wide stern, however, tend to trim heavily when heeling. Marchaj explains this as follows: more volume is absorbed at the stern than at the bow, causing the centre of displacement to move backwards. However, the centre of gravity retains its position and the boat wants to return to a state of hydrostatic equilibrium. It dives in more at the front and out at the rear, becoming top-heavy. This happens every time the boat rolls or heels, so it is also triggered by swell. The consequences are more heeling and more windward yaw. To avoid this, the geometry of the stern would have to be similar to that of the foredeck, as on the Vindö and also on the Hallberg Rassy. However, this is at odds with a lot of volume below deck and a spacious cockpit.

Or you can do it the other way round: adapt the bow area to the stern area. This is one of the reasons why new yachts are becoming ever rounder at the front.

The U-frame and the desire for a lot of volume below deck has another effect: the proportion of surface area above and below the waterline shifts upwards. The modern yacht has hardly any lateral surface area, but an enormous freeboard and high superstructures. This means that it offers the forces of nature the greatest surface area above the waterline, where they have the greatest impact. But the deeper a hull sinks, Marchaj teaches, the smoother its movements become.

Length runs - is that true?

More speed for the "motorhome" can also be achieved with a long waterline. The submerged hull is maximised with a straight stem or even one that is inclined aft. Very straight sides are required so that the hull can bend at right angles at the bow, and the U-frame must be held far forward. However, this also means that the volume from the waterline to the deck line does not increase as much as with the V-shape of the Hallberg or Vindö. If the bow enters a wave, it is not lifted upwards as much, but instead endeavours to sail through it, to put it simply. In modern ocean racing yachts, this is a desired behaviour. This is because going up and down, as on the Hallberg-Rassy, consumes more energy and therefore costs more speed than travelling through the wave - provided there is enough power from the rig. Compared to the sailing power of today's regatta boats, however, the Sun Odyssey is under-rigged, like most production cruising yachts. In addition, the large length-to-width ratio quickly increases the mould resistance. Ramming into the wave therefore slows the boat down considerably and also generates unpleasant jolts for the crew and hardly any increased speed.

What influence do the shape of the keel and rudder have?

The shape of the appendages is also due to the speed. The keel and rudder are deep and narrow and have a high length-to-width ratio. According to Marchaj, the greater this ratio, the more favourable the ratio of lateral force to resistance. In terms of speed, a short, deep keel is faster than a long one and also more effective against drift. However, this is particularly true in smooth water and at high speeds, i.e. in medium winds. In rough seas, when the yacht gets bogged down, it is constantly slowed down and accelerated again.

Now another law comes into play: the slimmer the hull appendages, the lower the effective angle of attack, the faster the current breaks away from them than from the long keels of the Vindö and Hallberg. However, this is fatal if the yacht is constantly trimmed as described and the helmsman has to react with large rudder deflections. The result is stalling, which can be recognised by strong drifting or uncontrolled listing. Not so with the old-timers. Thanks to their longer keels, they have a greater ability to hold their course and are more tolerant of disruptive influences. Steering is unnecessary over long distances, they find their own course.

The picture changes on the space sheet

Under these conditions, all three candidates have their weaknesses when sailing under sail and downwind - they virtually get stuck between the waves. A critical moment arises when the bow drills into the wave, the yacht brakes, the speed through the water and thus the current speed at the keel and rudder drops sharply. Yawing moments then occur on all three yachts. To counteract this, a quick reaction is necessary. The sooner the course correction is made, the less rudder deflection is required and therefore the lower the risk of a stall. This in turn could lead to a patent gybe or a sun shot.

The Sun Odyssey is somewhat easier to keep on course in aft winds than the Vindö, as it is more manoeuvrable due to its split lateral plan and reacts more quickly to corrections. The Vindö also moves rather sluggishly on this course. If the helmsman is not yet familiar with her behaviour, he often reacts too late and consequently has to apply more rudder. As the wheel also needs about three turns from full to full, this results in heavy cranking.

The Hallberg-Rassy also wins on this course and thus the overall ranking. It appears to be the most stable, but this is also due to the tiller steering. After all, the most direct and fastest corrections are possible via the tiller. The platitude "runs like on rails" is completely appropriate for her. In contrast, the Vindö is at a disadvantage: due to its downwind behaviour, its age and also because all halyards and outhauls on the mast are occupied, so trimming from the cockpit is not possible. The Sun Odyssey, on the other hand, does not cut a good figure in rough seas, especially against the wind.

The most common argument used to justify the uncomfortable sea behaviour of modern cruising yachts is that the target clientele - young families, older couples and charter crews - would no longer sail them in conditions above 4 Beaufort anyway. Most of them prefer to stay in the harbour. On the other hand, they are significantly faster in the lower wind range than their predecessors. The latter argument may be true. However, the reverse can also be applied to the other: Are people perhaps no longer going out in rough seas because the yachts are too uncomfortable for this?