Anchor special: Better anchoring, episode 2: 6 tips for the ideal anchorage

Hauke Schmidt

· 23.07.2025

In this special:

- Better anchoring, episode 1: Chain or line, how long?

- Better anchoring, episode 2: 6 tips for the ideal anchorage

- Better anchoring, episode 3: safely run in the ground bar - 9 Manoeuvre

Choose a secluded bay instead of a crowded marina or simply anchor off the beach and savour the evening atmosphere? Anchoring offers more than just a free overnight stay. Those who turn away from the stream of harbour commuters often discover something new. This can happen right on your own doorstep - or more precisely: next to your own harbour jetty. A yacht moored off the coast seems to magically attract other sailors, which often leads to a spontaneous decision in favour of the anchorage: "See how beautiful they are moored there? We could try that too." Even without a guide yacht or area guide, you can discover many a gem - a close look at the nautical chart is enough.

To ensure that the anchoring adventure remains a positive experience, it is important to observe a few basic principles.

Protection from wind & sea

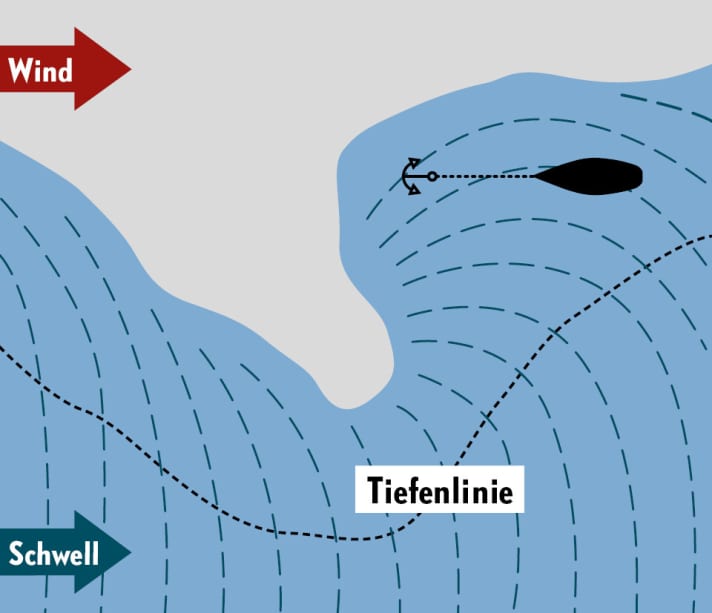

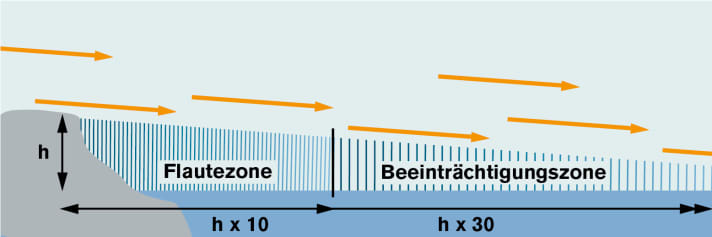

The most important rule is: always anchor to leeward of the coast, never to windward and never with the wind parallel to the coast. This raises the question: Does the potential berth match the wind direction? It's not just about the current conditions, but also about the weather forecast for the planned anchorage period. An up-to-date forecast is therefore essential.

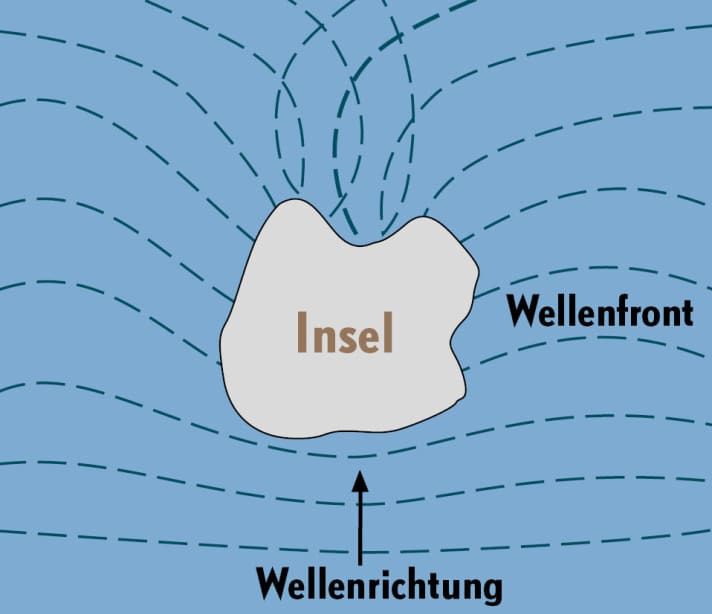

The next view is of the coastal contour. In principle, you can anchor behind any coast if the wind direction is stable. However, inlets offer more protection in wind shifts and appear more cosy. The stronger the wind and waves, the more important the shape of the bay and how the depth contours run.

If the coast offers no bays, the wind direction should be as close offshore as possible. Experience has shown that, depending on the wind strength, it starts to get choppy if the breeze deviates by more than 30 degrees, as the swell starts to run along the coast.

Keep an eye out for pipelines or underwater cables marked on the nautical chart. A safety distance of 300 metres should be maintained from such structures. The same applies to cable buoys or no-anchoring zones. It goes without saying that fairways and harbour approaches are not suitable for mooring. This is particularly relevant in narrow areas: Directional or sector lights must not be obscured.

In nature reserves, national parks or biosphere reserves, there are sometimes very restrictive navigation regulations that severely limit anchoring or at least prohibit shore leave by dinghy. Information on such rules can also be found on the nautical chart.

Suitable water depth

Once it is clear which coast offers a lee shore, the water depth comes into play. It is important to find a compromise that suits the yacht's draught. As the anchor gear can absorb different amounts of energy depending on the water depth, the weather conditions also play a role. However, this aspect only becomes significant in strong winds or very high swell, which is why we will limit ourselves to the draught.

Water depths between three and five metres are ideal for most yachts. Greater depths require more chain or line. However, the distance between the keel and the seabed should not be significantly less than one metre; after all, there must be enough water under the fin even with waves and when swooping. A sudden shift in the wind, for example due to thermals breaking away over land, must not cause the boat to run aground. Especially in very light winds, it is almost impossible to rule out the possibility of the boat swerving towards land and thus into the shallows. The closer the required depth is to land, the better the site is protected from the wind. A pronounced shallow water strip requires a correspondingly greater distance from the shore; it therefore becomes uncomfortable there sooner in fresh winds.

In addition to the absolute depth, the gradient of the bottom is a selection criterion; the flatter the bottom, the better for anchoring. On steeply sloping ground, the iron finds it difficult to hold and breaks out easily. The depth contours should therefore not be too close together.

If the water depth does not allow a complete swing circle, a second anchor attached to the stern can help. As it lies in deeper water, more chain or line must be used.

Good anchorage reasons

Keyword floor: Not all surfaces are equally suitable. Sand is ideal, the anchor usually grips at the first attempt and develops maximum holding power. Heavy seaweed growth requires more attention. There is usually good holding sand under the seaweed, but not every ground anchor will succeed in digging in. In addition, seagrass beds are important habitats that are affected by the anchor. You should therefore avoid them and try to anchor over an uncovered patch of sand.

Silt, clay or stony ground are consistently difficult, as the anchor grips poorly and does not develop its full holding power. Clay and loam are particularly tricky, as the anchor seems to hold very well once it has taken hold. However, when overloaded, the harness detaches from the ground with a whole clod. The clay usually sticks firmly to the anchor and prevents it from digging back in. Therefore, if in doubt, a second anchor should be used on clay and silt soils to distribute the load.

The type of bottom to be found at the potential berth can usually also be found on the nautical chart

Find peace

In addition to the nautical aspects, the anchoring experience is of course also influenced by the surroundings. This includes the bathing activities of a lively campsite as well as a busy coastal road or agriculture with livestock farming and the associated odours.

The nautical chart does not necessarily help with these points. It is therefore advisable to scout the mooring in question from the air using Google Earth or similar services.

Have a plan B ready

Rarely does a bay offer the desired protection in any wind direction. Therefore, more attention should be paid to the weather when anchoring than in the harbour. However, there is no need to panic if the development suddenly deviates significantly from the forecast. A sufficiently dimensioned and well-run-in harness will not fail immediately. However, you shouldn't try to sit out the weather change for too long either. At the latest when you get into a leeward wave situation, it is time to leave the anchorage.

To keep the adrenaline level low, manoeuvres for leaving the anchorage should be played through in your head. For example, before going to bed, ask yourself the following questions: What is needed to get the boat ready for sea again? Is the anchor winch ready for use? Is the dinghy ready for towing? Are the sails lashed down weatherproof? Are the deck and cockpit clear, or are there still cushions lying around? What does it look like below deck?

As a rule, the cosy chaos can be cleared with a few simple steps so that a night-time emergency start runs smoothly. Just knowing that you are prepared for this calms the nerves of both skipper and crew.

It is also advisable to look for an alternative when searching for an anchorage. This can either be another bay or a nearby harbour. It's not just about finding an alternative place in case the wind shifts, but also in case the bay you have chosen is not as suitable as you thought.

Don't despair too soon

Venturing into unknown waters harbours a certain amount of risk. Even if you follow the recommendations given in this article to the letter, you won't always find the perfect anchorage. But you shouldn't let this put you off. Even experienced skippers are not immune to sudden swells or swells from a distant shipping lane causing restless nights. Or the farmer spreading slurry on his fields that very afternoon.

However, spending the night as a packager in an overcrowded marina can also be unpleasant. If, on the other hand, you have anchored, there is no need to queue at the sanitary facilities in the morning. After all, there is a huge outdoor pool behind the bathing ladder. This alone is worth studying the nautical chart carefully.