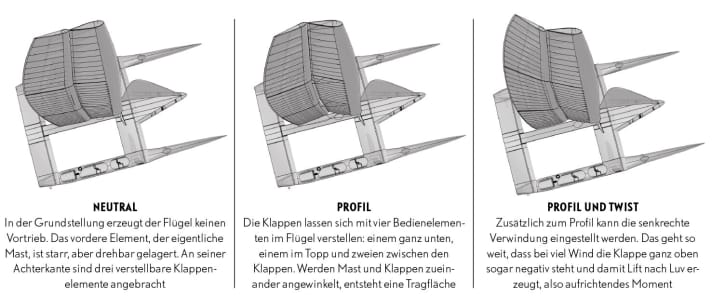

As in the previous Cup, the catamarans are mainly powered by supposedly rigid wings. These consist of the front, fixed part, the actual mast, as well as three adjustable flaps and are a composite of ribs and vertical beams, covered with foil.

The outer shape, the profile, of the mast and flaps is standardised for all, as is the structure of the mast. The structure of the flaps, on the other hand, is optional and can be flexible in different ways. The vertical gap between mast and flaps is important in order to increase the flow speed on the leeward side of the flaps. Unlike before, it may no longer be adjusted on these cup catamarans.

An explanation of how the Wing works

The three flaps are individually adjustable. This makes it possible to modify the profile depth of the wing and the twist of the leech. This is done using four lever arms: one at the bottom of the wing, one at the top and one between each of the flaps. Each of these arms can be controlled individually.

Compared to the previous cup, great progress has been made in this area. This can be seen from the outside by the fact that the arms that used to protrude from the side of the wing are now almost invisible and have been greatly miniaturised. This benefits the aerodynamics. All teams use hydraulics to adjust the flaps, but the solutions differ.

If the sailing crew wanted to adjust the tread depth on the move, for example, they would now have to operate four different lever arms. However, no electronic aids are permitted for adjusting the wing and, unlike with foils, no energy may be stored for adjusting the wing. The crew would therefore have to simultaneously apply pressure to the hydraulics and adjust the wing in four positions.

As this is too many tasks at the same time and would therefore have a high potential for error, all teams are likely to use so-called differential drives. These are lever arms to which adjustment lines are attached at increasing distances from the axis of rotation. If the lever is then operated via hydraulics, the lines travel different distances depending on the distance to the axis of rotation.

Alternatively, the three flaps can be operated directly via hydraulic cylinders in the sash. This is achieved via oil flow rates and the so-called master-slave configuration: If one hydraulic cylinder, the master, is adjusted, the others, the slaves, automatically follow suit. To ensure that they cover different distances for a different twist, they have different cylinder diameters, i.e. volumes. This means that the entire adjustment of twist and profile is coupled in itself. In addition, the twist characteristic - whether it is linear or non-linear - is preset on land, depending on the weather conditions. When sailing, the crew then only has to select the profile depth and strength, but no longer the type of twist, i.e. trim flatter on upwind courses or more bulbous on downwind courses.

In this way, it is also possible to trim the upper section of the wing negatively. This is mainly used when there is more wind, when the wing is already generating too much power and can no longer be fully travelled. It could then be positioned neutrally at the top in order to generate as little drag as possible. However, the negative position causes a pull to windward instead of leeward, which generates a righting moment.

The entire wing is pivoted and the angle of attack is regulated via a sheet. This leaves the crew with only two trim lines: profile depth, twist and angle of attack.

Tiny little genoa - or none at all

In addition to the wing, Genuas are operated in three different sizes depending on the wind strength: 36, 23 and 16 square metres. This seems small compared to the wing with its 100 square metres.

However, as the cats reach very high speeds, up to three times the true wind, even in light winds, the apparent wind on board also increases quickly, especially at the cross. This is why the foresail area must be reduced early on, as otherwise it would only increase drag. In addition, the wing is inverted in the upper part of the sail when there is more wind. However, a high genoa would accelerate the wind in this upper area from the wrong side, namely downwind instead of upwind as desired.

Recently, the New Zealanders were even on the training course without a genoa in relatively strong winds. Perhaps an indication that the headsail quickly becomes a brake instead of providing additional acceleration.

The big Cup guide: In the America's Cup special in YACHT 12/2017 you will find all the information and background to the sailing event of the year. From 24 May at the kiosk or digital here.