Anyone who completes the infamous Race to Alaska has a story to tell. Especially those who make the 750 nautical miles from Port Townsend in the US state of Washington through the notorious Inside Passage to Ketchikan on the coast of Alaska on small, self-built trailer boats. One of them is Joachim Rösler. Born in Stuttgart, he has a degree in business administration and has been sailing since his youth. After a career in the publishing industry on both sides of the Atlantic, he is enjoying his retirement in the USA, enjoys paragliding - and is passionate about taking part in raids: multi-day regattas for small dinghies and multihulls such as the Everglades Challenge in Florida or the longer and far more extreme Race to Alaska.

This year, he took part for the third time. However, it was no longer single-handed, but for the first time together with his girlfriend Zoë Sheehan Saldaña, an artist who lives and works in New York. The boat that Rösler had in mind for the adventure was not available to buy. So without further ado, he set to work designing and building his "Kairos 4Two" himself and then transporting it across America to the West Coast. The result was a rather unusual sailing vessel with three hulls and three masts. However, in the Race to Alaska, where no motor power is permitted, but muscle power as well as wind power is, the trimaran is not out of the ordinary. The abnormal is completely normal here.

The conversion inspires the designer

"Kairos 4Two" is a further development of the Angus Row Cruiser, a single-handed boat that Rösler launched in the two previous participations. It was originally designed by the Canadian extreme adventurer Colin Angus, who actually had an efficient touring rowing boat with an articulated hull, slip berth and plenty of storage space in mind. However, because many of his customers wanted additional sails, he ended up equipping it with outriggers and small open skiff-style rigs. The end result was a hybrid of a rowing and sailing boat.

"It's amazing how scalable the Row Cruiser concept is," says Angus, looking at Rösler's "Kairos 4Two". What's more, the German's boat has inspired him to design a larger model himself.

The material used was sheets of marine plywood - six millimetres for the hull, four millimetres for the deck - which Rösler cut himself and assembled using the stitch-and-glue method before reinforcing them with glass fibre fabric and West Epoxy on the outside and inside. He made smaller parts using the kiwi-preg method, placing soaked fabric on a plastic film and then removing the excess resin with a window squeegee. This saves weight.

"Kairos 4Two" Clever components in detail:

The mast must be lowered to set the sail

The boat is just under seven and a half metres long, around three metres wide, weighs around 180 kilograms empty and carries a payload of around 200 kilograms. Through-battened sails of one and a half to five square metres can be set on three unstayed carbon fibre masts, which requires a crew member to go onto the foredeck or aft deck to lay the mast and take down the respective sail. A tricky task, especially in heavy swell. There are a total of five sails on board; each one fits on every mast.

The boat also has a rowing station with a roller seat. There is also a mini cabin fore and aft in the 1.16 metre narrow central hull. In between, a cockpit tent provides a little more sheltered living space. You won't find a galley or even a toilet; the toilet is provided by a bailer. A dry suit is part of the personal equipment for tours in higher latitudes.

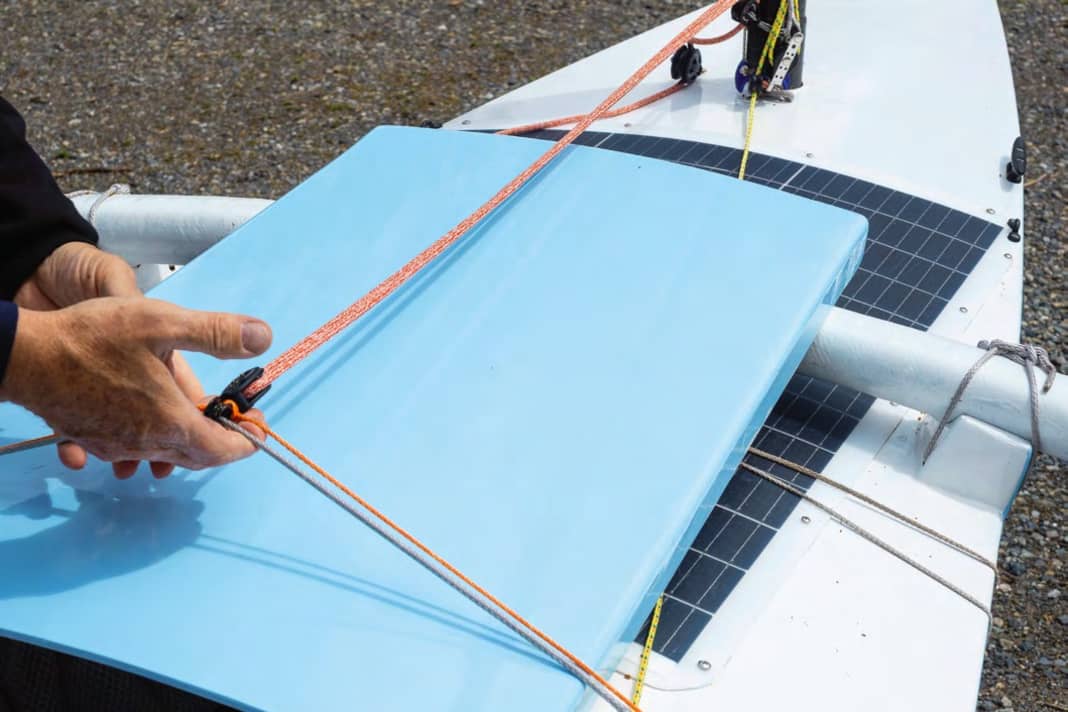

The deck features stainless steel fittings, ball-bearing blocks and lightweight synthetic rigging. Rösler also attached great importance to the clean installation of the on-board battery and a stable, smooth-running sliding mechanism for the forward hatch, which must not damage the 130-watt solar module mounted on the foredeck when it is opened. This is because the power supply for the navigation and autopilot runs from it. Under muscle power, "Kairos 4Two" reaches a cruising speed of four to five knots in shallow water. According to Rösler, this can be maintained in hybrid mode, i.e. when rowing with the sails set, for a whole day if necessary. In flat winds, this is an important distinguishing feature compared to larger touring boats such as dinghy cruisers.

Not an adventurer, but a "risk manager"

"You can't do a race like this on adrenalin," says the skipper, referring to his experience from the two previous participations. He made it to the finish line once and had to give up once due to a broken mast base. You have to find your rhythm, take regular breaks and stock up on essentials along the route whenever you get the chance. As he and his team mate only want to sail during the day, the two cabins with enough space to stretch out are an important design aspect. Rösler's tactic: "Arriving is about speed. We reckon it will take us three weeks to reach Ketchikan. The position doesn't matter - the main thing is to reach the destination!"

"You can't do a race like this on adrenaline. It's all about finding your rhythm"

Rösler, who sees himself as a risk manager rather than an adventurer, prepares the boat and equipment for the endeavour with the meticulousness of a financial accountant. Stainless steel tools, freeze-dried food rations, individually packed in bags and carefully labelled, plus tinned food, coffee, snacks and spirits are stowed away exactly according to the packing list. A cruising guide, tide atlas and paper nautical charts are also on board, just in case. The water supply, on the other hand, only needs to last for five days. The bottles can easily be refilled from streams or waterfalls along the route.

Another advantage of the "Kairos 4Two" is its extremely shallow draught, which allows it to take refuge in shallow bays that keelboats or larger multihulls are denied. Heavy anchoring gear is therefore superfluous, with only a small Danforth joining the journey.

A few days before the start, "Kairos 4Two" is fitted with an experimental rudder: a gift from a 505 sailor. It seems to suit the boat well in light winds as it gets up to speed under full sail and unladen. The height upwind that can be achieved with the off-centre and profiled centreboard is impressive. Rösler estimates the turning angle in such conditions at around 90 degrees - a significant improvement on the boomless Hobie rig he used to use. The main hull cuts through the water calmly and smoothly, a sign of efficient hull design. Later, when it starts to rise, the skipper goes to the aft deck to lay the mizzen mast, strip the sail and stow it neatly rolled up in the cockpit. Both the boom vang and the safety line for the mast can be quickly attached and detached using carabiners during the manoeuvre. "We reef sooner rather than later," explains the skipper, who takes the sails away before the conditions become critical.

"Kairos 4Two" is pretty to look at

"Kairos 4Two" is pretty to look at on a deep space sheet course with the sails in the double butterfly position. When the breeze takes a break, Rösler sits on the planing seat to demonstrate hybrid operation with sails and rudder power, while Sheehan Saldaña takes a seat on the aft cabin.

"The crew is very exposed on the open boat. Dry suits and good sun protection are essential"

When slightly heeled, the 2.44 metre short Amas, the outriggers, which are lashed to the Akas, the beams, with Spectral lines, become wave piercers on which the water flows away cleanly thanks to the streamlined deck shape. Kairos 4Two" is steered from the cockpit, with the carbon fibre tiller optionally available in a cleat. The Simrad T10 autopilot, which draws its power from a lithium-polymer battery, which in turn is connected to the solar panel via a controller, is mainly used when rowing. Mobile phones with the Navionics app and the corresponding nautical charts are supplied with power on board by portable Mophie batteries, which in turn are charged either by the main battery or by alternating current on land. Rösler is aware of the vulnerability of the Apple Lightning charging cables, which do not tolerate salt water and need to be stowed away well protected.

The team knows and trusts the "Kairos 4Two"

As team "Fix or Nix", Rösler and Sheehan Saldaña are well prepared for the start. Unlike some of their competitors, they have a tried and tested boat that they can trust in "Kairos 4Two". This gives them time and leisure to take care of the details, including those that contribute to well-being and thus to a good mood on board. "My benchmark for success? That we still like each other after crossing the finish line," jokes Zoë Sheehan Saldaña in the YACHT interview shortly before the start. And adds: "Not immediately, but after a few days."

Assessing risks, carefully studying wind and weather forecasts and also incorporating conditions and changes on the water into their route planning - all of this is routine for the pair thanks to their sailing background. In addition, their experience of paragliding, where behavioural or material errors can have far more drastic consequences, helps them to always act with a great deal of caution. And yet, the prologue to Victoria in Canada, which is around 40 nautical miles long, also presents them with an enormous challenge. A huge ebb current meets a stiff westerly head-on and, after the start, stirs up dangerously high and steep breakers in an area known locally as the "cabbage patch". For some participants, these are beyond the realms of possibility, resulting in various capsizes. Helicopters and lifeguards have to be called out to fish shipwrecked people out of the 13-degree cold waters of the North Pacific.

From huge waves to calm, everything was there

The "Fix or Nix" team and Colin Angus on a smaller Row Cruiser managed to stay out of the worst of it, but had to fight hard for a whole day before reaching a safe harbour undamaged to wait for better conditions. "We surfed huge waves for two hours at a perceived speed of five knots and still lost ground before we were able to free ourselves," summarises Rösler. While he steered astern to keep the stern in the rolling crests of the waves, Sheehan Saldaña was busy navigating and steering. The pair finally tackled the passage to Victoria two days later under rudder power, in calm conditions and with a pushing current.

"When it suits you, you have to step on the gas and put in the miles. If you don't take advantage of these opportunities, you'll fall behind very quickly"

The difficult conditions at the beginning are a warning to the participants. As a result, many sail rather conservatively. Instead of pushing themselves to exhaustion every day, Team "Fix or Nix" also takes it easy in order to save energy. The waters off Canada's west coast are good for a few surprises. Depending on the weather conditions, you can suddenly find yourself in a complex, virulent and completely unpredictable mix of gusts, wind jets and tidal currents.

But when it's right, you have to step on the gas to make up valuable miles. "There were only a few days when that was possible," explains Rösler afterwards. "If you can't take advantage of these opportunities, you quickly fall behind." In the end, there was only one boat behind team "Fix oder Nix", which finished 18th after 21 days, 7 hours and 25 minutes in Ketchikan and rang the obligatory finishing bell at the jetty. The winners around professional skipper Jonathan McKee, who had sailed on a 44-foot carbon racing yacht, had already done this 17 days earlier. Rösler is nevertheless satisfied: "They stayed within their time frame and, above all, arrived. Unlike 13 other crews who had to give up.

Despite some exhausting days, Joachim Rösler and his team-mates never seriously thought about giving up. On the contrary, says Zoë Sheehan Saldaña: "We got through it well together. And we still get on brilliantly."

Race to Alaska: a course with pitfalls

The Race to Alaska, which took place for the first time in 2015, started this year on 13 June as usual with the prologue from Port Townsend in the US state of Washington to Victoria, 40 nautical miles away. This is the main town on Vancouver Island in the very south of the island, which in turn lies almost 80 nautical miles from the western Canadian metropolis of Vancouver on the edge of the north-east Pacific. To get there, the participants had to cross the infamous Strait of Juan de Fuca, which separates the USA from Canada at this point. Due to a thunderstorm on the start day, many crews struggled to reach the first stage finish. The break until the start of the 710-mile second leg to Ketchikan in south-east Alaska was therefore shorter for those teams that had waited for better conditions in Port Townsend.

- More info at r2ak.com

Technical data "Kairos 4Two"

- Length over everything: 7,47 m

- Width3.05 m (centre hull 1.16 m)

- Displacement (empty): 160 kg

- Payload: approx. 200 kg

- Draught5 to 91 cm

- sail area: max. 12 square metres