The orange-coloured tip of the upturned foil looks like the dorsal fin of an aggressive shark upwind. To leeward, the T-shaped hydrofoil ploughs through the sea far below the water surface. FlyingNikka" is not yet flying. The hull does not enter the new element without resistance. The procedure resembles the rearing up of an aircraft that seems to stick to the runway just a few metres before take-off. The helmsman holds a sharp course and the three-man crew make micro-adjustments to the foils and sails, which are at maximum belly in the wind; they are deprived of all the propulsion they have to offer. With the J2 - which is still to rise - there are 220 square metres of sail in the wind, which results in a sail load factor of 7.8 with a take-off weight of seven tonnes.

Two days before the start of the Maxi Yacht Rolex Cup, the wind in northern Sardinia is blowing at just under ten knots. "FlyingNikka's" boat speed gradually increases and after topping the wind speed, the airstream comes into play. As soon as the apparent wind has gained the power of the vectors, the sails generate their own pressure. We fly! The 19-metre-long carbon racer makes 23 knots with an apparent wind angle of 20 degrees. As the foil arm now carries almost the full displacement, the trimmers flatten their sails, whereby a telescopic device on the luff fitting stretches the foot of the main. The board-like profiles are needed in order to be able to sail at acute apparent wind angles and to reduce drag. Now everything that stands unnecessarily in the apparent wind slows you down. Accordingly, you don't want to expose yourself to the 30 knots by standing up and prefer to aim for the escort boat pushing across the sea to assess the boat's speed.

A real push for the "FlyingNikka"

The fact that "FlyingNikka" takes off so early despite the two-tonne fixed keel is also due to a piece of mechanics. Instead of the launch and trim tabs on the trailing edges of the foils used in the America's Cup (AC), "FlyingNikka" relies on an alternative lift aid, which the development team led by Irish designer Mark Mills was the first in the world to introduce: At the end of the T-foil, the entire wing tilts up and down over the full span. "This gives us a real push. The AC flaps are good for high speeds, but can cause torsion in the wing," explains Alessio Razeto during the dieselisation. With their system, angles of attack from zero to 15 degrees are possible, explains the Team Manager and Head of Sales at North Sails Italy.

With the 150 square metre Code Zero, it is even possible to foil from 8.5 knots, provided the underwater hull is free of slowing fouling. The foils, designed by profile guru Nat Shaver and built by ReFraschini in Italy, are designed for loads of ten tonnes and, unlike the wings of the AC75, are neither ballasted with lead nor strictly symmetrical. They generate the necessary lift and the elevator, a smaller T-foil at the end of the rudder blade, acts as an elevator. A hydraulic cylinder tilts the rudder stock in the open tail by plus or minus six degrees.

The construction method

Last year, "FlyingNikka" only broke away from the water at twelve knots or more. Lacorte is not on board today, Razeto is in charge: "We have saved around 300 kilograms, among other things by using a non-battened main and a lighter boom." The railing supports are shaped like sushi sticks and sink directly into the hull instead of being supported by feet. When stepping onto the concave foredeck with its tapered flanks, you are tempted to test the stiffness by bouncing slightly. A knock reveals ultra-thin laminate. "FlyingNikka" was created at King Marine in Valencia as a sandwich construction made of carbon prepregs, Nomex and foam. An aluminium honeycomb core was used in areas of the hull that are potentially exposed to impacts. The keel, which is required by the stability criteria of the Offshore Special Regulations for participation in World Sailing regattas, prevents uncontrolled, overly violent ups and downs in flight. The fixed keel also serves to remove cooling water and is a safeguard against capsizing, which is a recurring problem with the AC75.

Flying safely with the "FlyingNikka"

Roberto Lacorte has been sailing since he was a child, but is also a motor sportsman and has already taken part in the 24 Hours of Le Mans six times. "We have created an extremely powerful boat that flies and is one thing above all: safe," says the pharmaceutical entrepreneur from Pisa, who has already sailed "FlyingNikka" overnight. His last two boats had the same postfix in their names. His collaboration with Mark Mills began with the 62-foot-long "SuperNikka" and resulted in four victories in the Maxi Cup. Lacorte originally had a conventional 77-foot racer in mind before switching to the uncompromising 60-foot maxi with T-foils - without ever having foiled himself, either on the boat or on the board. Only after the decision to build was made did he start two 69F campaigns to get himself and his crew fit. "Without the two and a half seasons, we wouldn't have been able to sail 'FlyingNikka'," says Lacorte, who won the world championship title in the 6.90 metre one-design class in the first year.

The sea breeze increases steadily, foamy wind waves roll towards the Costa Smeralda and the 78-foot catamaran "Allegra" rushes past at a good 20 knots. As the J2 has suffered damage to the clew, the sails need to be changed. All three headsails, including J3 and J1, run on a self-tacking track. The J1 provides the support boat on which all the sails are stored. Even the rigger only comes on board for repairs and uses a tablet to get live updates on the loads. "Earlier, the J2 was too small, now the J1 is slowly becoming too big," says Razeto, describing the dilemma in twelve knots of wind. Now the optimum windward speed (VMG) is set, while the boat speed downwind is almost 30 knots. Power is also generated via the skirt, the profiled sail below the boom, which sweeps across the aft deck like a broom and has its own traveller. "It makes up ten per cent of the mainsail area, which is enormous," says Razeto, who dispenses with the additional cloth completely in strong winds. Sensors help him choose the right sail: "Last year, we had load sensors that always showed values that were too high, so we trimmed the sails. Now everything is right."

Control is at theMaxi Yacht Rolex Cupannounced

We turn below two Js that push towards us under Spis. In flight mode, control rather than power is the order of the day. The sail trim is now aimed at keeping the loads in check, which are generated by the high righting moment of the foils. The traveller sled whizzes back and forth robotically on the horizontally curved track, but the mainsail is never heavily feathered. "If we left it too open, the mast would come down. The sheet is our protection, we don't have backstays. This makes the Cunningham all the more important for rig trim," explains Razeto. The hydraulics use Dyneema shackles to pull up to six tonnes on the structured luff of the North Helix headsails, which take up 80 percent of the total load. Only 20 per cent remains on the forestay.

The leeward shrouds flap down from the 35-degree swept spreaders. On the other hand, the carbon fibre filaments upwind tug at the titanium terminals with eight tonnes, as the Toughbook of navigator and flight controller Andrea Fornaro reveals. The all-rounder sits in front of the on-board reporter on two stacked yoga blocks and switches tirelessly between five overlapping programme windows using the mouse trackball. With one-sided shroud loads of more than 18 tonnes, the attached profile mast of Southern Spars could buckle, informs Fornaro.

The Maxi-Foilerei

Another aspect adds to the complexity of maxi foiling. In contrast to foil surfing, whether with a kite, wing or windsurfing sail, the hydrofoil cannot be adjusted to the changing load in the longitudinal direction. The height regulation of the foiling moths via a sensor on the bow is also not possible. FlyingNikka" therefore also relies on the mechanism on the lower main wing, whose angle of attack changes up to four times per second, to ensure a stable flight attitude. This usually happens automatically and synchronised with the elevator and side arm, which can influence the dive depth and flight altitude via its inclination. The many adjusting screws are orchestrated by Fabrizio Marabini's flight control system. Its protocols are fed by the team's input and the system also learns with the help of artificial intelligence.

A large number of sensors collect data during operation. The flight altitude is measured aft of the long skeg, which softens the touchdown and ensures smooth transitions from displacement to flight. The value must not exceed 1.20 metres, otherwise the wings will draw air. On deck, the distance increases to around 2.50 metres, although it feels much higher. The sea surface is furthest away from the centre of the boat, so take-offs or serious crashes are most likely. To prevent this from happening, Fabrizio Marabini was constantly on the move during the two-hour preparations before casting off, always keeping an eye on his laptop. The specialist in fluid dynamics has made a name for himself with the New Zealand America's Cup team and co-founded FaRo Advanced Systems, a company that manages a wide range of projects from flying water taxis to super yachts.

Marabini even allows the foils to extend and retract automatically via pre-programmed sequences during tacking and jibing. You don't notice much of the splashing of the new leeward foil and the subsequent fountain on board. Ducking and holding on is the motto during the dynamic changes of direction, which are interrupted by occasional soft splashdowns in the lower limit range. The respectable g-forces make it clear why impact protection waistcoats and helmets are mandatory on board. "The steering wheel needs to be moved very quickly, the high reactivity requires small steering commands. When we sail 'FlyingNikka' at the right speed, it feels like driving a GT sports car," says Lacorte, who was active in the LMP2 class in the World Endurance Championship.

The wind has picked up to 16.6 knots and we are heading for Porto Cervo at our top speed for the day of 32 knots. It feels surreal and now actually fast. The seats aft to leeward are covered in spray from the foil mast, whose two spray rails prevent heavy showers. Unfortunately, the flying pleasure is anything but silent. The engine is running all the time and the engine speed and volume are permanently high. The main consumer is the Cariboni hydraulic system. The two winches on board, electrified carbon drums from Harken, are used exclusively for setting the sails. The sheets are raised and lowered by hydraulic cylinders that receive their fluid from two pressurised circuits of 500 and 350 bar. The 80-kilowatt Yanmar engine is open and not soundproofed in the stern and is designed to run even when heeled at 90 degrees. After five hours, of which around three hours were spent foiling, the level of the 200-litre, crash-proof diesel tank had dropped to 20 percent.

The next step

The crew huddles in two trenches one behind the other, as if in a bobsleigh. Within the six-man race crew, the helmsmen's seats at the front and those of the navigator and foil operator aft are immovable, while the trimmers for the mainsail and foresail always switch sides during manoeuvres. In Porto Cervo, many eyes are on the "FlyingNikka" crew. They handle the pressure with ease, have fun ashore, laugh a lot and live together. It is not a collection of sailing mercenaries who come together a handful of times a year. Lacorte has spent over ten years building up his team and comes across as approachable and open. He wears a three-day beard, team shirt, sailing shorts and stops for a chat at many corners. The wiry Italian and his team have created what he calls a "sustainable design" and are willing to pass on their expertise or negative form. He himself is eyeing up the new small America's Cup class AC40. "We have the experience, that would be an option for us. Above all, you get the attention around the Cup. And you would be ready for the next step afterwards," laughs Lacorte.

The Maxi Yacht Rolex Cup is not about winning in Class A, the IRC rating of "FlyingNikka" is in the realm of fantasy. They are more concerned with putting themselves in the limelight and flexing their muscles a little, as the training beat suggests. "We were seen as dangerous," recalls Roberto Lacorte of last year, when they reported just four months after first launching and were given their own start out of caution. The nimbus of the outsiders is still underpinned by the berth at the end of the main pier of the Yacht Club Costa Smeralda, from which the martial foiler is separated by two metre-long sandwiches of flat fenders. Under water, polystyrene parts are applied to protect the wingtips before entering the harbour.

Alessio Razeto is satisfied with the training day, although five to six knots more would have been possible in the regatta set-up. With a tacking angle of 110 degrees, you need the speed advantage. Downwind, the true wind angle of incidence was 130 degrees. "With a full crew, we go to 138, sometimes 140 degrees," says Razeto. The apparent wind angle does not rise higher than 50 degrees and also dictates sails that are trimmed quite flat, even if there is a slight chop in the sheets and, unlike with the AC75, the direction of the waves is not necessary to determine the true wind direction.

Finally, the question arises of how to land when the mainsheet cannot be abruptly furled and the tilt mechanism at the lower end of the T-foils does not allow any movements in the negative range. Up to a certain point - thanks to the apparent wind - the wind resistance can be increased and slowed down somewhat in foiling mode by means of bulbous sail trim. But "FlyingNikka" ultimately comes to a standstill when it abruptly starts to luff. The 19-metre foiler then performs a controlled sun shot and lays down on its cheek, quite conventionally.

Technical data

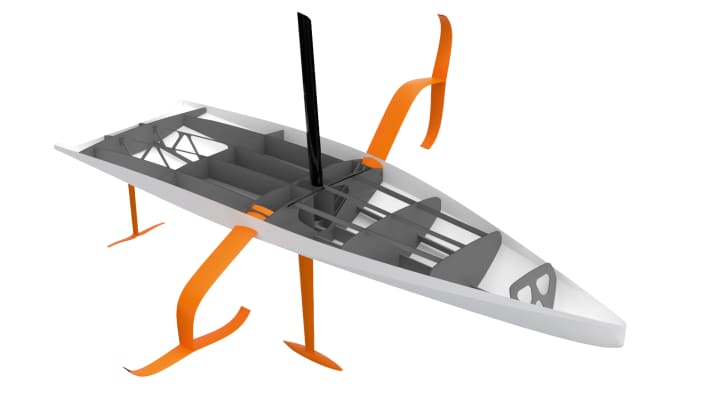

Rare geometry:The rudder with elevator, two swivelling foils without ballast and a deep keel with lead bomb are unique. Many bulkheads and stringers characterise the interior

- Designer: Mark Mills

- Torso length: 19.0t0 mSpain

- Material: Carbon/Nomex/Foam

- Torso length:19,00 m

- Width:6,00 m

- Depth:4,50 m

- Weight: 7,0 t

- sail area: 220,0 m²

- Sail carrying capacity: 7,8