The ride lasts just ten metres. Then nothing works. Firstly, because the keel is probably stuck in the mud at a depth of a good three metres, here in Enkhuizen behind the quaint sailing pub "het Ankertje". Secondly, because the engine is not working. It beeps, the rich gurgling of the exhaust has stopped. The "Flyer" is lying ingloriously crossways in the fairway and won't move an inch. Fortunately, there is never any traffic here. So: stocktaking. Something with the diesel supply. New filters in, bleed, continue.

Such details cannot stop sailing enthusiast Gerhard Schotstra. The lanky man in his late thirties is the father of the idea of bringing the legendary yacht back to Holland. The ship that won the 1977/78 Whitbread Round the World Race in a calculated time and therefore over all. The one that founded a series of Dutch participations in the legendary race, just think of the runner-up "Philips Innovator" in 1985/86 with the up-and-coming co-skipper Bouwe Bekking, the "Brunel Sunergy" in 1997/98 or the victorious "ABN Amro" in 2005/06.

1977/78 the "Flyer" wins the Ocean Race

The reactivation of the regatta yacht "Flyer" at this point in time seemed to make sense; Schotstra was able to skilfully use the momentum of a new Dutch campaign for his idea. The race, which has been called the Volvo Ocean Race since 1998 and is now known as The Ocean Race, was restarted in October 2014. And Bouwe Bekking took part for the seventh time (which was a record), this time with the new "Brunel" as the Dutch ship.

More about skipper Cornelis van Rietschoten:

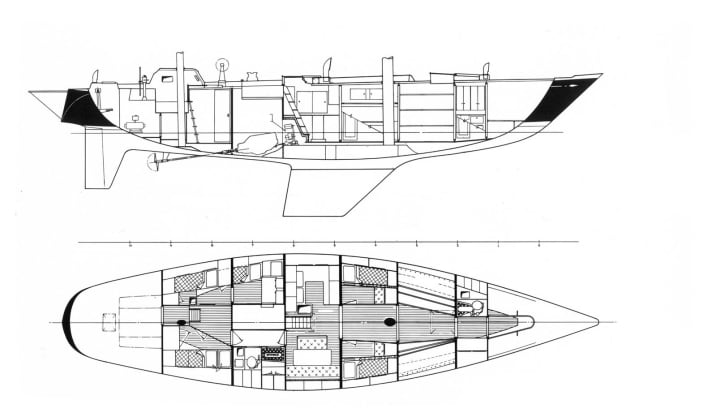

The two yachts, "Flyer" at the time and "Brunel" later, could hardly be more different despite their identical length of 65 feet: one made of carbon and trimmed for low weight, the other of aluminium, ketch-rigged and designed for fast, but also almost comfortable ocean sailing, including oven, wooden interior and oilskin drying locker.

New challenge with the regatta yacht

The skipper at the time, a certain Cornelis van Rietschoten, was a nobody on the sailing scene at the start. Nevertheless, he changed it.

As a successful industrialist, he sought new challenges in retirement - and found them in sailing. He was no daredevil, on the contrary. His preparation for the race was more than meticulous, almost pedantic. That was new. The ship already had 10,000 miles on the clock before the start, for testing. The crew was carefully selected, right down to the cook, who above all had to be seaworthy. So while van Rietschoten's men were well prepared, this was often less true for some of the other campaigns.

"Great Britain II" even had paying guests on board and, all the more remarkable, crossed the line first after 134 days. However, the more important calculated score was won by the "Flyer", which took two days longer to complete the round-the-world trip in stages. And the preparations that had been made on her set new standards. A young blonde from New Zealand orientated himself on them. Still without a chance at the first appearance of the "Flyer", he travelled on board the British Robin Knox-Johnston and learned. His name: Peter Blake. Both Blake and Knox-Johnston were later knighted.

"Flyer" is one of the most famous yachts in the Netherlands

At the following Whitbread at the beginning of the eighties, this blond giant had already put together his own team and chased the flying Dutchman on his delicate "Ceramco New Zealand". However, van Rietschoten won the race again - with the regatta yacht "Flyer II", a Frers design, as before by calculated time and this time also by sailed time. However, Blake had lost his mast on the first leg due to a material fault.

Incidentally, the "Flyer" was called "Alaska Eagle" for about 30 years when she was still white. It was under this name that she took part in the third Whitbread in 1983/84 under the skipper and then new owner Neil Bergt. Now rigged as a slip, she finished ninth out of 27 participants.

Back to the present. The engine is running again and pushes the large blue regatta yacht through the bascule bridge and the old sea lock out into the Krabbersgat. For the first time since the "Flyer" returned home to the Netherlands, all sails go up. Goosebumps on board.

The refit was extensive- now the regatta yacht is renovated again

However, the brand-new cloths with their ball-bearing mast slides still hook a little on the virgin rails on the masts, which are also still new. This was a thorough refit over the last few months. Back at her original shipyard, Royal Huisman in Vollenhove, it quickly became clear that "just painting her dark blue again" would not be enough. "The old paint system was no longer strong enough for this. So everything had to come off, all the fittings and the paint," explains Schotstra. "And once the winches had been dismantled anyway, they were completely overhauled, and so it goes on. The newly built but original doghouse had to be adapted, a sprayhood had taken its place in the meantime and the electrics were no longer up to scratch. That's the way it is with old ships," grins Schotstra.

You can tell that all of this makes him happy, he has arrived here and is the right man for the job with his calm but determined manner. Perhaps van Rietschoten would even have included him in his crew, who knows. The boss had laid down a few rules for this crew: There was to be no shouting on board. Swearing was also forbidden, as were complaints about the food and conversations with political content.

The refit of the regatta yacht should be based on the original

The IJsselmeer has an estimated ten knots of wind - the wind gauge is not yet connected - in store for the second maiden voyage. The sails fill up and the "Flyer" picks up speed. The crew pause reverently. This is what it was like sailing with van Rietschoten back then. The ship should be as true to the original as possible, albeit with adaptations to the present day: "Today we have Dyneema halyards; steel ropes are simply no longer state of the art, even if they belong here originally," says Schotstra. Rodrigging is also a concession to modern times. When sailing, everything runs smoothly, everything works, the cloths stand well. Solemn silence on board.

It is a shame that van Rietschoten, who has since passed away, will not live to see it. One detail shows what this boat means to the Dutch: Schotstra's two daughters were given time off work by their teacher so that they could be on the maiden voyage with their dad. They are probably learning more here than at school anyway. That's possible in sailing-mad Enkhuizen.

The "Flyer" returns once again to the Ocean Race

Then it's time to trim: a little more halyard tension here, the outhaul there, a bit of sheet here. And then the GPS on the smartphone - the plotter and log, you guessed it, are also not yet connected - reports something like a good six knots. Schotstra stands still on the aft deck. The regatta yacht is sailing, to his credit. The stress of the last few weeks seems to have paid off; what is still missing is peanuts.

When she was still called "Alaska Eagle", back in 1982, she was given away after the race to an academic sailing school in California. There she sailed around 185,000 miles in 30 years, 40 times across the Pacific alone and three times across the Atlantic. In the meantime, she was given a new engine.

Inside, everything is as it used to be

However, nothing has changed in the interior of the regatta yacht. Walking below deck is like travelling back in time. It is unimaginable that the teak surfaces have survived generations of sailing students so unscathed. Or that they are there at all - after all, this is a racing yacht. For example, the lovingly crafted wooden panelling on the mast at the front is striking.

In the current Volvo Ocean Race, sailors are sawing off their toothbrushes to save weight and using a carbon toilet. By contrast, the panelling on the mast of the participating yacht from 37 years ago weighs as much on its own as all of Holland's toothbrushes put together. It is not needed for sailing, it is only there for visual reasons. Beautiful and pointless - on a racing yacht.

Or the galley: also made of teak, it has two huge refrigerated compartments and a three-burner hob with oven. There are wine glasses in the cupboards, one for each crew member. "They're original," says Schotstra confidently. None of this is necessary if you only eat freeze-dried food. But who wants that on an ocean passage? Van Rietschoten certainly didn't, which is why he had a trained chef on board. Incidentally, meals were served in the mess. They sat on leather-covered sofas. It goes without saying.

"Secrets" on board the "Flyer"

Another story revolves around the skipper's cabin. Van Rietschoten is said to have kept scotch in the lockable cupboard there for ceremonies such as the baptism of the equator. The crew discovered this and worked their way from aft through the bulkhead to the scotch. Would a sailor today drill through the carbon stringer of his VOR 65 to get to a shot? Probably not.

The regatta yacht also survived a front with 55 knots of wind just before the finish in the Solent. The spinnaker flew to pieces during a jibe. And while the crew collected its remains, the large boat drifted towards the rocks of the Isle of Wight due to a wind shift. Only a remarkable series of manoeuvres and sail changes prevented the worst from happening. Imagine that: Unassailably in the lead, the ship runs aground 20 miles from the finish. You can only imagine the strength this unleashes in a crew.

The "Flyer" could certainly tell dozens of stories like this; after all, she has more miles in her wake than most yachts will ever sail. And she is far from old. Her condition is formidable, new activities await her. She will continue to sail off the Dutch coast. Where she once came from.

However, it was built for long, fast ocean passages. In this respect, the regatta yacht is still ahead of many current designs.

This article first appeared in YACHT 21/2014 and has been revised for this online version.

Technical data regatta yacht "Flyer"

- Design: Sparkman & Stephens

- Material: Aluminium

- Overall length: 25.53 m

- Width: 4.98 m

- Draught: 3.05 m

- Weight: 25.2 tonnes

- Ballast/proportion: 11.4 t/44 %

- Sail area: 230 m²

- Sail carrying capacity: 5.2