Could Eva take the dogs back? Torsten, 66, and Werner, 72, wait outside the gate until she puts the dogs on a lead. Only then do the two of them enter the property. It is their property. It is also her house, where Eva lives with the dogs. And it is their shed, more like a hangar, which rises above the land further back, in front of the bank between the now stately trees. A functional building made of corrugated iron, 30 metres long, 20 metres wide. A treasure inside. A dream. But also a 31.35 tonne mortgage.

Werner inserts a bar key into the lock of the rusty door, turns it and pushes the handle down, but it resists. There is a massive chain over it, but it only serves as a deterrent. Perhaps Eva has put it on, just to be on the safe side. A strong tug, then the door swings open. And there she stands, this giant from a deep-sea yacht. In the middle of the vault of the hall roof. Good grief!

It's a familiar sight for Torsten and Werner. They have been coming here for a good 20 years, previously with their families. Before that, Gernot, 59, Werner's younger brother, and Bernd, 65, were also there, not forgetting their many mutual acquaintances, friends and girlfriends, and the children who ran around and helped on the property.

It was a cheerful community, united behind a bold idea. They all regularly celebrated together in the Polish town of Stepnica, where the waters of the Oder flow into the Szczecin Lagoon. The town is located on a bulge, a dredged channel leads to the fairway, on into the Baltic Sea and from there into all the seas of the world.

Setting sail from Stepnica, that was the plan a few years after the fall of communism. They wanted to build a huge ship, big enough for everyone, strong enough to travel around the world. Just do it. They have always been masters at that.

In Eva's purple-painted house, the TV is on, a car is parked, the dogs are testing their leads. A kitchen is set up on the first floor, with an old school map of the world hanging on the wall. This is where the self-builders and their families stayed during the working weekends. Ladders lead from the chambers to sleeping alcoves under the roof. It was a lively place when everyone was living there, fuelled by euphoric anticipation.

Initially, they soon came 20 times a year. Now nobody has spent the night in the beds for a long time. This visit is the first this year. The "Avalon", as the mighty steel yacht is called, rests dusty in her slipway. She was once a pleasure. Now she is a burden.

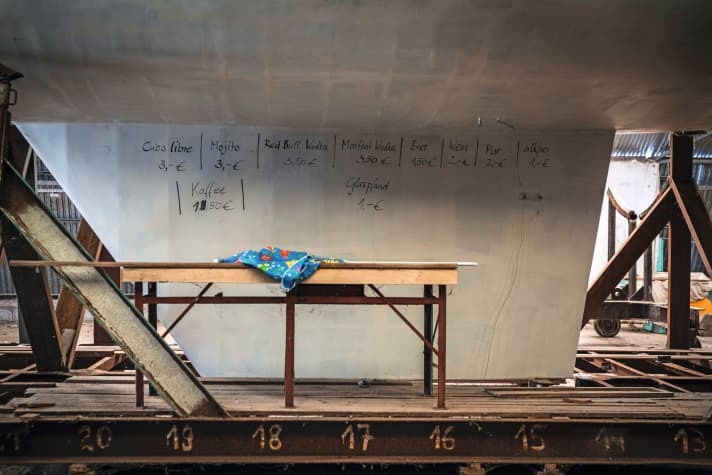

Almost nothing has changed since last year. And yet: "Almost all of the teak poles have been stolen," says Werner. They were last placed on a homemade stage, another relic. Torsten, Werner and the others had tried to increase their budget for boat building with parties so that they could continue building. "Cuba libre

3 €", "Coffee 1.50 €" is written on the mighty keel, in front of it the remains of a bar. It was one of many ideas to get the "Avalon" afloat. But it wasn't enough.

Apart from the ship, the hall is almost empty. The yacht, whose steel plates are welded together with longing, is massive: The hull measures 20 metres in length and more than five metres in width. You have to stand in front of it, in the hall in the idyllic countryside north of Szczecin, to realise the audacity of the project.

Can dreams gather dust? Stairs made of scaffolding parts lead up two storeys to the deck. "We've installed wire mesh here," says Torsten, directing his gaze to the railings. So that the children could get up and down safely when they were little. A long time ago.

Werner, Gernot, Torsten, Bernd - they come from the former GDR. Shouldering big things was their thing. Despite the fact that the authorities didn't like it, and precisely because they didn't like it. They once wanted to organise a festival with a circus tent without any permission. Someone had a mayor in their circle of acquaintances and let them organise it on municipal land. Hundreds turned up. "From the Stasi's point of view, it probably got a bit out of hand," says Werner. Bernd once organised a group meeting in the village of Werben, where everyone had to come by a different means of transport. Gernot and he paddled there in a folding boat. They still talk glowingly about the week-long meeting today.

Werner was already a photographer before reunification: "We took the photos for the record sleeves and autograph cards of well-known GDR bands such as Karat, Silly and City." One evening, he had a chat with Toni from City and Sibylle Bergemann, a well-known photographer. "And over the second glass, they were already talking about their trips to New York and the great tour to Lisbon." That hurt. "I was always the stupid one who hadn't been to Paris, Lisbon or anywhere else."

But Werner found a way out of the politically imposed confines. He suggested a photo book about Lisbon to the Brockhaus publishing house in Leipzig. "The Portuguese had left the socialist path late during the Carnation Revolution," he argued cunningly. It took a while, but he got the visa. Later, a "Stern" editor gave him daily assignments in West Germany, and the West German fee remained in Hamburg accounts. Splicing acquaintances, helping each other out - in this currency they were merchants.

Then came the reunification and new opportunities to travel. Gernot and Bernd, both restorers, received a commission in Munich: 400,000 West German marks in fees, spread over one and a half years and ten more helpers, but it worked. They embraced the world. The world embraced them.

"After Munich, six of our circle of friends met up regularly and everyone brought everything to the table," says Werner. Especially wanderlust. They set their minds on living at sea. That's how it started. There were two passionate sailors, but nothing more. The others at least knew: "We're a group that has made everything possible so far." This is how Gernot describes the beginning of the "Avalon" project.

The bold plan: to build a yacht for everyone and sail as far as possible for as long as possible. They estimate that a 30 metre boat would be enough. As restorers, Gernot and Bernd have the refit of a classic in mind. Bernd explores the possibilities on a trip to England and is offered a boat that might be suitable. But that is still at depth. "We quickly realised that transferring such hulls is not technically feasible."

So something new after all!

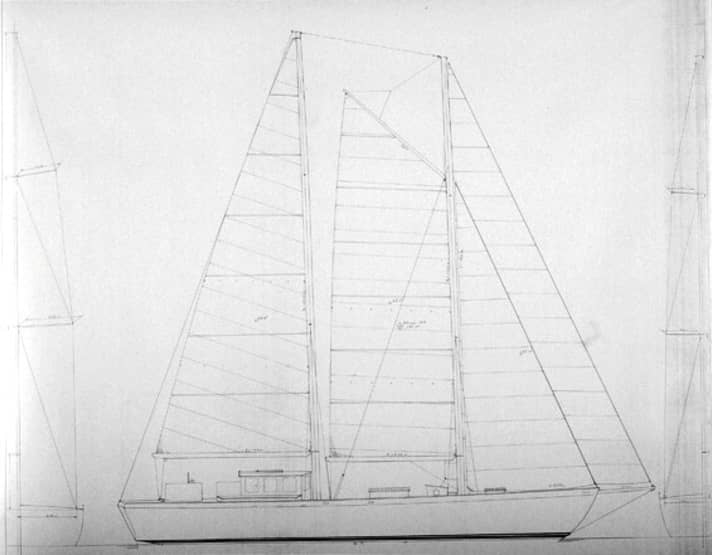

Designer Volker Behr from Bremen warns them about the legal hurdles for yachts over 20 metres in length. The men sail on the "Esprit" trial, a moulded and glued schooner he designed for a crew of 16.

The self-builders from the east join forces, Behr and his partner Jan Engelhardt draw them a round-the-world schooner with a spoon bow and classic yacht stern.

Nobody remembers exactly when it all started. It must have been in the mid-nineties. The friends found the property in Stepnica through acquaintances and bought it on a leasehold. Again through connections, they came across an unused KT 60 steel hall in the Berlin area, a standardised GDR building. In high spirits, the collective dismantles the hall and rebuilds it in over 600 square metres of self-cast floor slabs in Poland - driven by the feeling that nothing is impossible if they want it enough. And they are good at it.

The welding of the floor assembly starts overhead. "We got the steel sponsored," says Werner, describing the good fortune of those years. "It was brought to the hall free of charge in the required thickness and alloy from Thyssen-Krupp" They organise stainless steel from the same source. The frames are soon in place. The hull is completed within a few years.

Tractors pull it out of the hall, a 60-tonne crane turns the monster. A milestone has been reached! In a photo of this moment, the group looks proudly into the camera. "We were so daring that we wanted to sail to Sydney for the 2000 Olympic Games," Werner reminisces about his delight at the time. "We thought the city would become our sponsor," adds Torsten, "and we would become official ambassadors for Berlin. Diepgen was mayor at the time. He replied to our enquiry that unfortunately he couldn't contribute anything apart from an official flag." "Did we ever get that?" asks Werner.

They would have preferred financial support anyway. In the post-reunification period, the Deutschmark and later the euro became the most important currency, rather than relationships, cohesion, vision and ideas.

Many things are lost in the following years. For example, the on-board toilet, which is specially purchased to fit the pedestal below deck on which it can sit enthroned. "Who's actually got it?" asks Torsten. "The model ship should be with me," remembers Werner. And recounts how they not only built the "Avalon" in a scaled-down version, but also planned the layout in advance with enormous effort. "A mock-up of the cabin was created in Gernot's studio using wood and stretched canvas." They built the foredeck, which no longer had room there, in his garden.

Now there is no sign of any of this. The hull of the "Avalon" remained empty like a gravel barge. Plywood bulkheads merely indicate the compartment partitions. The interior of one of the two adjoining aft cabins was carefully cut out of polystyrene, glued and positioned. However, its parts lie broken on the neatly sealed frames and stringers. Work has been at a standstill ever since.

The propeller shaft is installed, as is the engine and the hydraulic rudder system in a separate aft peak. Apart from that, the entire cabin has no other details. "Do you know where the portholes are?" asks Werner. "They should be with our Polish accountant."

Having started out as a utopian dream, the self-build is now just a standing asset. "The flame has really dimmed since 2005," Werner remembers the time ten years after the start of construction. "We had run out of steam. I blocked it out. I don't know how you felt, Torsten. I didn't want to make a decision. We didn't do anything for five years. Nothing at all!" Work and family took priority for years.

"It all came to a head when the first two people left," says Gernot today. Torsten joined as a "new colleague" at the time, he is a packer like the others. But it still became too much. "At some point, the women said: 'Keep going up there and building, it's taking too long'," says Bernd, looking back on the time that got "Avalon" into troubled waters.

Things are going well professionally, there are still enough jobs. Werner establishes the photo agency "Ostkreuz", founds a school with the same name, and both are soon regarded as institutions. But shipbuilding on the side? "We only checked from time to time to see if the tarpaulin was on. I didn't have the courage to say, listen, I can't do this anymore," admits Werner. "We thought something would fall from the sky, something would happen," says Torsten. But nothing happened.

Many of the "Avalon" co-operative keep their heads above water with charter sails, including on the "Esprit". Two of the self-builders buy their own yachts, swapping the really big dream for the small, manageable one.

Despite all the initial euphoria and idealism, there is always money involved. When the first deposits are used up and the sailors drop out of the project, the remaining shipbuilders issue shares, lovingly designed by a graphic artist. Each share costs 5,000 marks. The value: a berth for six weeks; "The value of this voucher expires 5 years after commissioning" is written on it. Only eight or nine were sold - and all but one or two were bought back when boat building came to a standstill. "We had to admit that, well - it's not going to happen that quickly," says Torsten.

"Avalon" is considered a mystical place, a sacred island between the worlds of the gods and mortals. They wanted to create such a place using only their energy. Of course, they were aware that, due to superstition, ship names are not announced until the ship is launched. But why wait? So far, everything they had taken in hand had worked out.

"The ship is the only big thing I haven't managed in my life," says Gernot. "Experience has shown that we shouldn't have started at all," is how Bernd sees the project today. "What a lot of money we've wasted. We could have financed a second-hand 18-metre boat. Not only would it have been cheaper, it would have been ready to sail."

On deck, under the freshly stretched tarpaulin, Werner shows the two carefully crafted skylights, whose lids also serve as benches. "This is where the table would have gone," he says. Abruptly, the "Avalon" rolls to anchor in a swell, the rigging casting long shadows on the deck. Werner looks across the bow to the imaginary horizon. He smiles softly.

What moments that would have been - on board, on a cruise. "Werner always cooked well on board," Bernd would later say on the phone. And: "Someone has to wear the hat, I wanted to be the helmsman and navigator." He left the ship as such.

"We don't really love each other anymore," Gernot says today about his friend Bernd, who once sat in the folding boat with him and still pulled out of the boat project. He doesn't say a bad word, but you can feel the disappointment, the pain that the dream remained unfulfilled.

"I'm 72 now," Werner emphasises several times. Their strength is dwindling, they don't have time anyway and they won't get any credit. And the numerous children, christened the "youth brigade"? "We wanted to give it to them," says Werner, "everything, without obligation." They didn't want it. "They didn't have the dream. They realised what it had already cost us," he adds. There are no exact figures, but they have certainly invested 400,000 euros in the ship so far. They reckon it would cost that much again, including rigging, sails, electrics, furnishings and equipment up to the launch. Money they don't have.

That they would start a YouTube channel like "Sampson Boat" to finish their "Avalon" after all - illusory. "There was a crowdfunding campaign once, but it was all half-hearted. We're also not the generation that posts on Instagram."

And now? The ship is here. The steel tubes on which the hull rolled back into the hall are now bending. So far there is no rust anywhere. The three remaining men are paying alimony for this: Werner, Gernot and Torsten are still putting 250 euros a month into the limited company that they founded for the construction so that everything remains standing, they say.

Eva gets a handout for looking after things a little. "If there's no one here, then doom is inevitable," Torsten is certain. Enough has already been taken. Sitting on wobbly chairs by a cable drum, they eat sandwiches that Torsten made in the morning. Eva brings coffee.

"I don't even know how we used to do it, where we found the time," asks Werner, without hoping for an answer. The three of them have recently been looking for buyers. The price is probably negotiable. What is not up for discussion is that should the "Avalon" ever sail, they will have to be on board.

- Length 19,90 m

- Length over all 22,50 m

- Waterline length 16,90 m

- Width 5,42 m

- Draught 3,00 m

- Displacement 31,35 t

- Ballast 8,45 t

- Mast height above waterline 22,30 m

- Sail area 200 m²

Nils Theurer

Freier Mitarbeiter, Südkorrespondent