With cork waistcoats in the rowing boat and on the oars: These were the beginnings of sea rescue on the German coasts 160 years ago. They could be bakers or blacksmiths, perhaps even a fisherman on free watch, rowing against the raging sea to help their distressed seafaring neighbours. Equipped with little more than a good dose of courage and determination and a certain knowledge of the area.

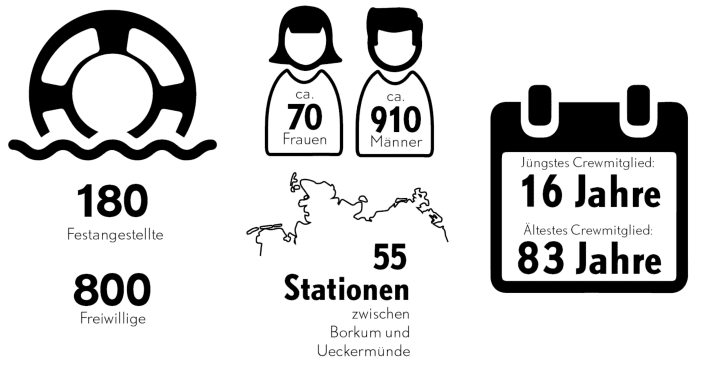

When an emergency call is received by the Bremen Maritime Rescue Centre today, a coordinated search and rescue chain begins. "It can be vital to set this chain in motion early enough. If in doubt, better too early than too late; that's what we're here for," emphasises Maximilian Ohme. The 20-year-old is one of around 1,000 sea rescuers - including 70 women - who ensure that the DGzRS is ready for action around the clock.

In 55 harbours between Borkum, Helgoland and Ueckermünde, rescue cruisers with permanent crews and smaller rescue boats with volunteers are stationed. Whichever crew is called out, they must be familiar with complex manoeuvres, navigation electronics, engines, rescue equipment, first aid and, without fail, the special features of the local area.

Even today, the careers of rescue workers can be very different. Some have many years behind them as seafarers, on the world's oceans in cargo transport or as fishermen on the coast. Others are recreational skippers or completely inexperienced in seafaring. But all of them want to rescue people from distress at sea together, and all of them have proven themselves to be team players and reliable - these are among the most important personal requirements for this job.

The DGzRS is always on the lookout for new volunteer sea rescuers at all volunteer stations. "We need a large crew in order to guarantee our operational readiness around the clock and in all weathers," explains Ralf Baur, spokesperson for the sea rescuers, adding: "However, when we advertise jobs for permanent employees, a large number of qualified seafarers always apply."

How to become a sea rescuer

Requirements for volunteers

- Place of residence near the station

- Minimum age 16 years

- Valid health card (fitness for sea service)

- Ability to work in a team

Permanent employees: Requirements rescue worker

- nautical knowledge such as a sailor's/ship mechanic's certificate, time spent in the fishing industry or similar.

- 16-hour basic first aid course

- Valid health card (fitness for sea service)

- Ability to work in a team

Requirements for foreman or machinist

- nautical and/or technical patent in merchant shipping or fishing

- General operating certificate (GMDSS radio) for navigators

- 16-hour basic first aid course

- Valid health card (fitness for sea service)

- Ability to work in a team

For decades, both permanent employees and volunteers were mainly trained on the job. Depending on their professional background, they travelled as rescue personnel, engine drivers or navigators. They were gradually taught the rescue business itself on board and in training courses.

Since 2019, the DGzRS has bundled all of its training and further education programmes under the umbrella of the Maritime Search and Rescue Academy. It is based on four pillars and is based at various locations: at the sea rescue stations along the North Sea and Baltic coasts, at the simulator centre in Bremen and at the sea rescue training centre in Neustadt, together with a training fleet attached to it. This fleet also includes a small sailing yacht and, more recently, a training ship, the "Carlo Schneider", which travels to the volunteer stations as a kind of "floating classroom".

The volunteer rescuers' stations are not permanently manned. When an emergency call is received by the Bremen Maritime Rescue Centre, all available colleagues from the surrounding area are alerted - but not everyone can rush to the boat at any time. Sometimes there are only three people on board, the minimum for a mission. They have to be able to rely on each other and be compatible as people.

New members therefore start out as candidates. They take part in the weekly station evenings and go out on exercises. If the chemistry is right and a doctor confirms that they are fit to work at sea - another prerequisite - they can begin their training as a lifeguard. Basic training in first aid and resuscitation is mandatory, as is a ship safety course. This is also required by the Seeberufsgenossenschaft, which insures both employed and volunteer sea rescuers on duty.

A ship safety course like this involves a lot of action at the training centre in Neustadt: the volunteers have to climb into life rafts, they practise leak defence, they learn firefighting or hover on a winch from a helicopter down to the deck of a boat. The courses have to be repeated at regular intervals. "They are our life insurance out there. If we find ourselves in marginal situations, we need to know how to get out of them," says Timo Jordt. The former paramedic has been a sea rescuer since 1998, deputy head of the Sea Rescue Academy and head of the training fleet.

Anyone who wants to become a boat skipper afterwards dives deeper into the subject matter. Although no licence is required to operate the lifeboats at the volunteer stations, you do need a recreational boating licence and SRC radio certificate, which can be obtained from the DGzRS if required.

Further courses teach the basics of search and rescue procedures and crew resource management so that the right crew is always deployed on a mission. After all, if you have to search for a missing person at sea at night, it can make more sense to send out a slightly larger crew with more searching eyes than if you have to tow in a pleasure craft with engine damage.

Another component is communication on board: even in stressful situations, everyone has to speak the same language.

The final part of the boat skipper training is a course in technical navigation. In practice, the training boat "Mervi" sails across Neustadt Bay in broad daylight with the blinds down. The crew in the darkened interior sometimes only come on board with basic navigational knowledge. A week later, they have mastered radar procedures and the use of AIS, GPS plotters and radio so well that they can find their way even in the thickest fog.

The crew and the station foreman decide whether someone becomes a boat captain after this intensive training. They know each of the candidates and know who can cope with a stressful situation on a mission and who they can trust implicitly, even and especially if the situation becomes dangerous.

The engineers on the lifeboats, on the other hand, do not need to be boatmen, but they do need to be rescuers. They do not even necessarily go out on missions. Their main task is to keep the boats ready for use at all times. This is why they complete a boat technology course.

Training also takes place regularly at the stations themselves. For example, with a comparatively small lifeboat that has to tow a 22-metre steamer with a displacement of 100 tonnes. This is anything but a simple endeavour. And it's not without danger either. One wrong manoeuvre or too much throttle and the towed vessel can cause the smaller lifeboat to heel heavily. It is no less dangerous if the lines cannot withstand the enormous load and break.

These and other exercises carried out with the mobile training unit at the volunteer stations come very close to what the men and women can expect in an emergency at sea. "Experiencing for real how your own lifeboat tilts under the load and the lines groan is a real 'aha' moment for many," reports Thomas Baumgärtel.

He is one of five instructors on the training ship "Carlo Schneider", which has been travelling from station to station since summer 2021 to train the volunteer sea rescuers. The son of a sailor, he has been sailing since childhood and joined the sea rescuers in 2003. Initially as a volunteer, he has been a permanent employee since 2006. The ship, which was specially constructed for training purposes and on which he has recently started sailing along the German coast, has two training consoles for navigation, similar to those in the lifeboats.

Around 20 volunteers can be trained on board over a long weekend. They, who are regularly available for assignments in their free time, used to have to spend several days a year travelling for training and further education. Now they can learn and practise many things at their own place of residence, together with their regular crew on their own boat in their home waters.

Baumgärtel clearly enjoys training the crews and sharing his many years of experience with them. It's different to imparting theoretical knowledge, he says, adding: "You listen better to people who can do it and who can tell you a little something than those who have read everything. That was already the case at school."

In the first season, line work, seamanship and manoeuvring are on the training schedule. The intensity of the individual modules can be tailored to the needs of the respective crews. Model ships are used to simulate harbour or towing manoeuvres and demonstrate the forces acting on a boat. Outside, what has been learnt is then immediately put into practice: Throwing mooring lines, steaming into the spring, casting off, mooring.

Another advantage is that the training boat's engine is identical to the one on the lifeboats. This means that the crew can also learn everything they need to know about the potentially vital propulsion system.

Some of the rescue workers have been in service for decades. Trying to teach them anything seems pointless. But learning is not a one-way street, Baumgärtel and his colleagues realise time and again: "We are in the middle of a real generational change. The seasoned rescue workers know their area, their boat and have already mastered many critical situations. They have an enormous wealth of knowledge that must be passed on if it is to be preserved. When we tell them that, they are happy to take part in the training courses."

When the journey of the "Carlo Schneider" continues, further points such as SAR basics, medicine and rescue scenarios will be on the programme. However, the training ship cannot and should not be a substitute for other components of the training programme, but rather a useful addition for the volunteers.

Anyone wishing to become a permanent sea rescuer must have maritime experience and a nautical or technical licence for higher tasks. The sea rescuers do not train their own seafarers, but teach them the sea rescuer trade in a two-year career training programme. Some of the candidates are external, others are longstanding volunteers.

Some have been sailing for decades or are experienced fishermen, while others have plenty of experience in searching for and rescuing people at sea and know their way around the local coast. In order to bring these different starting points to a common level, they have all been undergoing permanent career training for two years. One positive side effect is that up to twelve candidates from one year become a crew for the duration of the training. "They talk about everything, including mistakes - so that others don't make them," says Timo Jordt. Together with his colleagues, he has developed the career training programme, which begins with aspects of ship safety and SAR basics, just like for the volunteers.

The permanent staff also receive full training to lead firefighting operations or as paramedics. At the end of their training, they can serve as a rescuer, engineer or finally as a foreman on a rescue cruiser. The career path at management level is correspondingly demanding, both in the mechanical and nautical fields. This includes courses in occupational safety, operational and staff management and communication.

The latter is practised in the simulator centre in Bremen, and under anything but normal conditions. When the door of one of the five chambers closes, a very realistic-looking emergency communication exercise begins: with full load on all radio channels, interference from a cacophony of foreign languages and imminent danger to their own rescue cruiser, maximum concentration is required for verbal mission coordination. Neither wind nor waves are needed to make the participants forget that they are taking part in an exercise.

As structured as the training is, it must remain dynamic. That's why the trainers also regularly undertake practical training to ensure they are always up to date. Because, according to Jordt: "In rescue at sea, you learn something new every day. Our rescue vehicle moves on an element that never stands still and can always behave differently. This requires a great deal of flexibility from everyone involved."

Once a year on the North Sea and Baltic Sea, all the skills learnt are put to the test in large-scale exercises. Sea rescuers, navy and federal police at sea and also in the air simulate emergencies. Amateur actors pretend to be seriously injured, ships pretend to be wrecked. In action: volunteers and permanent employees who have never or rarely worked together before. And yet, thanks to their standardised training, they speak the same language and know the same moves.

Ultimately, the ideal scenario for everyone involved is for such exercises to remain the norm. However, in 2021 alone, the sea rescuers were deployed on more than 1,800 missions and rescued more than 300 people in acute distress or danger at sea.

What they want to pass on to sailors comes as no surprise. Timo Jordt can look back on 23 years of experience as a sea rescuer. He says: "Wear life jackets and have life-saving equipment on board." Many tragic accidents could be avoided if sailors were better prepared, emphasises his colleague Maximilian Ohme. "Anyone who goes out should switch on their head, think about the situation beforehand, about the wind and waves and the area."

Instructor Baumgärtel also warns against blindly relying on the technology. "It's good," he says, but there are more and more accidents today that might not have happened if the skipper had familiarised himself with all the circumstances.

The training career

- Level: Candidate

- Level: Trainee to become a volunteer rescue worker

- Level: Certification as a paramedic

- Level: Trainee as responsible boatmaster

- Level: Certification as responsible boat skipper

- Level: Qualification as a station manager, optional: certification as a machine operator after certification as a paramedic