Series: Sailing practice with Tim Kröger

- Rig trim Correctly adjust the mast profile with shrouds and stays

- Sail trim Giving the sails the ideal profile on all courses

- Optimal crossingSailing perfectly to windward with the right tactics

- Downwind sailing Cruising faster downwind with gennaker & co

There is hardly anything more arduous than tacking against wind and waves. It's a daily occurrence on regattas, it's simply part of the job to cover around half of the distance crossing. The cruising sailor, on the other hand, will try to avoid exactly that - and if I were him, I would too.

But this is not always possible. It is regularly necessary to master a course to windward. There are a few tricks to help you get round quickly and safely.

If the rig is set up as described in the first episode and the trim elements are also easy to operate, adjust and set, it will be easy to complete a cross in all conditions.

On racing yachts, the trimmers are in constant coordination with each other and with the helmsman in order to be able to react to even the smallest change and convert it into speed and height upwind. Every gust, every change needs to be utilised.

Every boat cruises differently

As different as boats are, so different are their performance characteristics. The upwind performance also has a lot to do with the shape of the hull and the underwater hull as well as the keel and rudder profiles. A classic long keeler, for example, has a completely different performance in the wind than modern cruising yachts.

Cruising yachts in particular often make major compromises. For example, people want to be able to enter small, cosy harbours or anchor in picturesque bays, which requires a shallow draught. Unfortunately, this stands in the way of optimum upwind performance, and you will then have a hard time cruising.

Nevertheless, these are tips that can be applied to any yacht and any boat. Every boat has strengths and weaknesses that need to be assessed in order to get the most out of this given framework and sail safely upwind to the next harbour. And ideally across the entire range of wind conditions.

Rules of thumb for cruising

In regatta sailing, there are a few rules of thumb that you should follow on the wind. For example, the long bow should be sailed first in order to approach the finish line as quickly as possible. If well-calibrated instruments are on board, the true wind direction is constantly kept in view to check whether this bow is still the long one, which brings the closest approach to the finish, or whether the wind has shifted or is currently shifting and the other bow is therefore the longer one.

If this trust in the instruments is lacking, the compass course can of course also be used to find out whether the wind direction is changing, the angle to the target is improving, i.e. whether I am still on a "lift", or whether the wind is dying and I am on a so-called header, as we announce internationally.

I've already described in previous episodes that we have fixed jobs and tasks on board when racing. When I was part of the French Corum Sailing Team around 1995, we had a very special allocation of tasks on upwind courses. In my role as pitman - the man on the halyards - it was my job to keep an eye on the true wind direction on upwind courses and to take an average value as zero on the starting cross. Starting from zero, a lift is then plus and a header is minus. This information is given in relation to the true wind direction or the compass heading as follows: +5, 0, +5, +10 and so on. These values are continuously communicated to the tactician in quick succession. This allows the tactician to orientate himself as to whether the boat is still on a lift or whether it is travelling at minus and should better turn.

If the helmsman hits the rhythm from pushing to gaining height and pushing again, the boat reaches its optimum on the wind"

On a cruising yacht, no one is going to sing out every 20 seconds whether the programme is currently plus, zero or minus. However, if you want to get to windward quickly, it is important to keep an eye on the true wind direction or the compass.

Trim the sails correctly for cruising

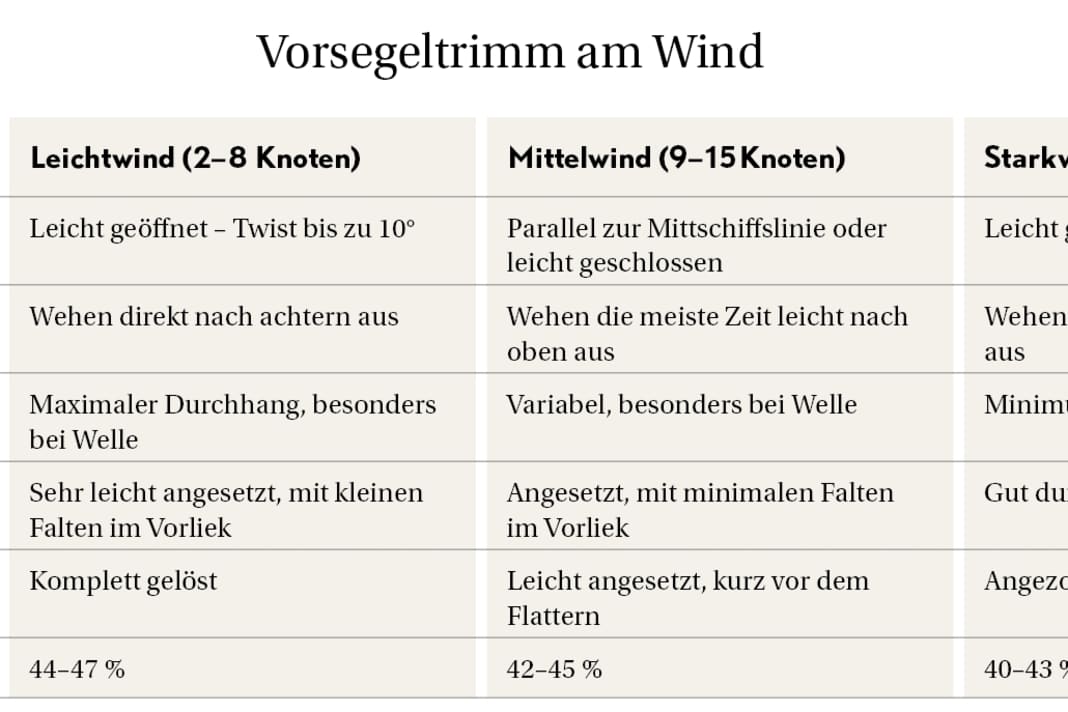

Sail trim plays a major role in fast upwind speed. And as conditions are constantly changing, these trim tables are designed to help harmonise the most important components.

In order to be able to steer the boat ideally in the wind, the sails must be trimmed correctly for the prevailing conditions. Then there is the helmsman's ability to concentrate in order to keep the boat in what we call the groove. You want to be on the optimum track, which results in maximum height.

Here too, boats are different. Let's assume the optimum case. The keel and rudder profile need to be flowed against in order to develop their lift. I'll try to explain this very simply: The smaller the surface area of the profiles, the more speed through the water is required for the profiles to generate lift, which in turn moves me faster to windward.

A comparison with aeroplanes makes this effect clear: a triplane can fly slowly due to its immense airfoil area and still have enough lift to stay in the sky. A jet plane with a small airfoil area, on the other hand, has to be fast in order to generate lift through the airflow.

Weighing up speed against height

Applied to yachts, this means that if you want to get the maximum out of the profiles under water, they need to be aerated. That's why it's literally not a good idea to keep the boat permanently upwind - i.e. the classic upwind tack. On the contrary, I should steer into the wind in such a way that I keep pushing a little, i.e. dropping slightly, until the sails, which are trimmed for "upwind", are optimally positioned to build up speed and thus gain height again, up to the point at which I slow down again - but not too slowly.

It's a very fine line, a very fine amplitude of steering movement that I'm talking about here. For example, if I tell a helmsman that he has to accelerate so that we reach our upwind target speed, this means: dropping a little, pushing a little until the speed is a few tenths above the target, then accelerating again a little and thus converting this gained speed into height until the game starts all over again.

An active mainsheet trimmer is important

If a helmsman can find this rhythm of pushing to gain height and then pushing again and is optimally supported by the mainsail trimmer to get into this flow, the ship will reach its optimum on the wind.

In gusty winds, the mainsail trimmer basically steers the boat so that the helmsman can minimise the compensating steering movement. This is because too much rudder movement damages the speed and therefore the height on the wind. The instruments, and in particular the wind lines, are the best indicator for finding my groove on upwind courses.

As we are not sailing on a limited and always the same grass pitch, the bumpier our pitch becomes, the higher the demands.

The influence of waves on cruising

Sailing downwind in waves requires additional attention to the factors mentioned above.

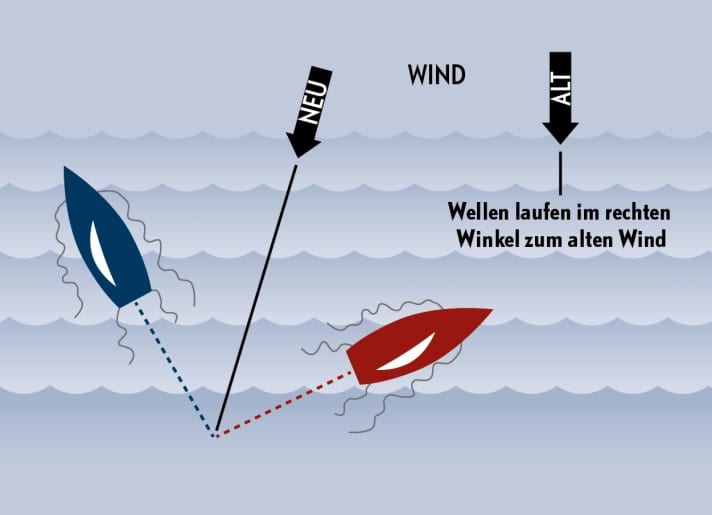

In most cases, the wave follows the most constant wind direction - not taking into account current or tidal influences.

In constant winds, we should therefore find approximately the same wave formation on both the port and starboard bow. From a turn of 15 degrees over a longer period of time, however, the wave tends to come from the side on one bow and rather bluntly from the front on the other. Both bows then require a different sail trim and slightly different steering skills.

The bow against the wave will be the slower one per se, and the boat will have a tendency to pitch into the waves and therefore be slowed down. Then I need more twist, more power in the sails to get through the wave at a higher speed. I have to push a little harder when steering to generate more speed and keep my yacht going. The other bow with the sideways wave is the smoother one, where I can gain a little more height, as there is less danger of abrupt braking due to a fall into the wave trough.

Waves or even heavy seas have a major influence on our performance on the wind. They rock the boat and make life difficult for us. That's why the expected wave patterns, in addition to the wind direction, determine our optimum path to windward.

There will be fewer waves under land or behind a headland. At sea, far from the coast, you can expect more waves and also high swell in strong winds. With offshore winds, you can also expect fewer waves under land. These are the regions where I want to sail.

But if there is no way out and I find myself at sea in a strong swell, I have to face the challenge and master it. The better I navigate waves, the better I master them, the more smoothly I reach my destination.

Correctly control waves when crossing

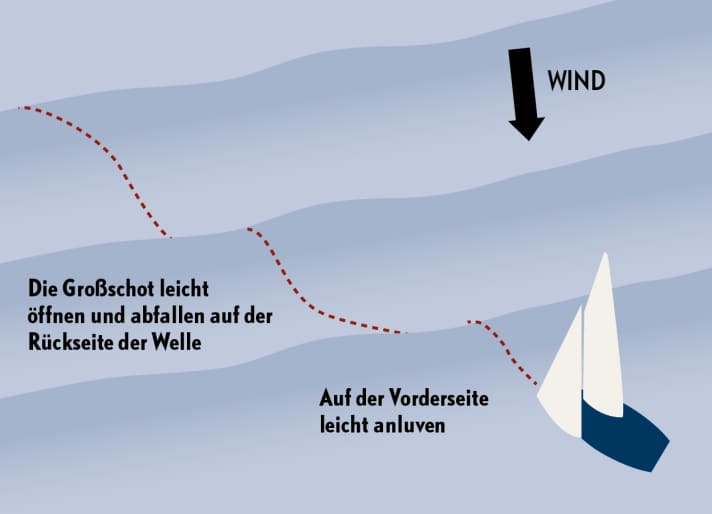

Ideally, I luff slightly on the front of the wave as I go up without losing too much speed. I then drop off on the crest and open the mainsheet to come down the back of the wave and build up speed again for the next wave.

On the crest of the wave, the mainsail must be opened at all costs in order to be able to drop and avoid windward pressure, i.e. rudder pressure. An attentive mainsail trimmer helps immensely at this moment to master the crests.

The greater danger, however, lies in approaching the wave. If you overreach to windward and are too high upwind on the crest, the wave can come under the leeward bow and you will be smashed to windward with the headsail standing back.

I experienced this in 1985 at the Admiral's Cup in the Solent when the boat capsized on the crest of the wave to windward. Being completely wet right at the start of the Fastnet Race in strong winds was an unpleasant experience.

Steering with a lot of wind and waves on the wind is a bit like skiing down a mogul piste. I try to avoid the rough zones and get my height and speed back in the gentler areas.

On racing yachts, the crew on the edge has the role of signalling the wind and waves. If the helmsman and mainsail trimmer know what is coming, they can react. Dropping, twisting the sail at the right moment - these are the actions that take place seconds after the announcement from the front.

The correct rudder position

However, it is also important to recognise how much rudder effect, i.e. how hard I actually have to steer in waves so that my boat does not become excessively slow due to the more intensive steering. There are two things to consider: firstly, the size and shape of the waves. Are they big or small, long or steep, and how close together are they? With small waves, you don't need to adjust the rudder as much, and not even in large swells. Medium-sized waves, however, can be a nasty challenge, especially if they are steep and follow each other quickly.

On the other hand, the dimensions and weight of your own boat influence how hard you have to rudder in waves. The shape of the hull also has an effect. Do I have a fine, narrow bow or a voluminous, wide foredeck?

These factors determine whether we avoid waves because they slow us down, or whether we power through because the boat can. All boats have one thing in common: the less rudder movement I have to make, the faster I am.

In a small crew without regatta experience, it is important to divide up these tasks sensibly. The person steering should have an unobstructed view forward of the waves and steer from windward in any case. In my opinion, you can only steer well from leeward in very light winds. Or under gennaker to see the luff better and be able to react. In windy and bumpy seas, steering from leeward is an absolute no-go for me.

Wind and wave

If you have to tack in a wave because the wind has shifted or the waypoint is now on the other bow, look for a place with relatively smooth water. That sounds easier than it is. But it is the right approach. After the tack, I then have the opportunity to accelerate better in this area in order to master the next wave.

The turn should be planned well in advance if there are a lot of waves. In smooth water, a quick turn can be realised without any problems, but in waves it becomes more challenging.

First, look for a calmer spot upwind - around 30 degrees from the bow, where there is a short distance to accelerate on the new bow before the next wave brakes.

Now the helmsman needs to concentrate and accelerate before turning the boat round. In waves, it is more important than usual to turn the boat quickly through the wind, as there is a high risk of being caught by a wave in the middle of the tack. You should also come out a little deeper than normal on the new bow, with a greater upwind angle than the performance data prescribes, so that the boat gets back up to speed more quickly.

So I come out of the turn lower, build up the speed and work my way back to my optimum speed for the conditions downwind.

It goes without saying that the sails must always be trimmed correctly during this manoeuvre. My tacking angles will also change with waves. They will become larger and the drift - i.e. the leeward shift - will increase.

In a strategic approach, i.e. when navigating from A to B, I have to take this into account. And if you want to make good tactical progress to windward, you also have to keep a constant eye on the wind and its rotation as well as the local conditions of the sea area in which you are travelling in order to take advantage of all factors.

And also so that the hopefully not so tiresome crossing doesn't become a cross and can be completed quickly.

In November, Tim Kröger will be giving a two-part YACHT webinar on the topics of "Correct cruising" and "Correct jibing". If you are interested, you can send your contact details to timm@yacht.de by e-mail. You will then be informed about dates and participation opportunities in the coming weeks.

Tim Kröger

In 1993, the 58-year-old was the first German to make sailing his main profession. He took part in the Whitbread twice and the America's Cup twice. Today, Kröger sails in the J-Class, among others, and is an author, speaker and coach.