Foiling: Foil special: What you need to know about sailing on wings

You can barely hear them, and you only see them briefly. They whiz past with a quiet hiss and leave only an inconspicuous trace on the surface of the water with their delicate stilts. Anyone who masters the filigree carbon fibre dinghy Moth can reach a top speed of 30 knots - and that with a tiny boat just 3.30 metres long and weighing a mere 35 kilograms. In no other class has foiling made such an impressive and lasting impact as with the International Moth. Within just a few years, the single-handed design class has almost completely metamorphosed from glider to foiler. Around 5000 units are registered worldwide today, many of which are foilers, including all the new boats.

200 starters from over 20 nations registered for the World Championships on Lake Garda in July 2017, and all of them sailed on boats with foils. The rule of thumb in the class is that a sailor weighing 80 kilograms can take off with a modern moth in winds of just eight knots. The centreboard and rudder are T-foils with horizontally mounted hydrofoils. The profile depth is adjustable on both foils. The rudder foil is trimmed via the rotation of the tiller arm, the main foil on the centreboard via an automatic resistance sensor.

Even if it looks light and weightless: Foiling with a moth requires a lot of feeling and practice. Only those who practise diligently will be "ready for take off" - and won't end up in the water again after every gust. The fact that renowned shipyards such as Beneteau also want to bring foilers in yacht format into series production opens up new opportunities to learn how to "fly". The Figaro 3 ( Click here for the photo gallery of the prototype ) by the French may build a bridge between professionals and amateurs, it could be a pioneer in series yacht construction. But it also shows the limits of physics. So far, only regatta boats that have been reduced to the bare essentials in every respect have really benefited from foils - such as high-performance catamarans or fast dinghies and sports boats.

Nevertheless, foils will shape the future of sailing. On the following pages, we explain where the trend comes from, how foiling works and which foil models are also affordable for beginners.

How the boats learnt to fly

The hype surrounding foils and "flying" sailing boats has only just really taken off. Yet hydrofoil technology, which still seems strange, if not outlandish, to most sailors today, has an astonishingly long history of development behind it. As early as 1861, more than 150 years ago, the Englishman Thomas William Moy built two fixed hydrofoils under a sloop, which he had pulled along a canal by a team of horses. According to tradition, the hull is completely lifted out of the water.

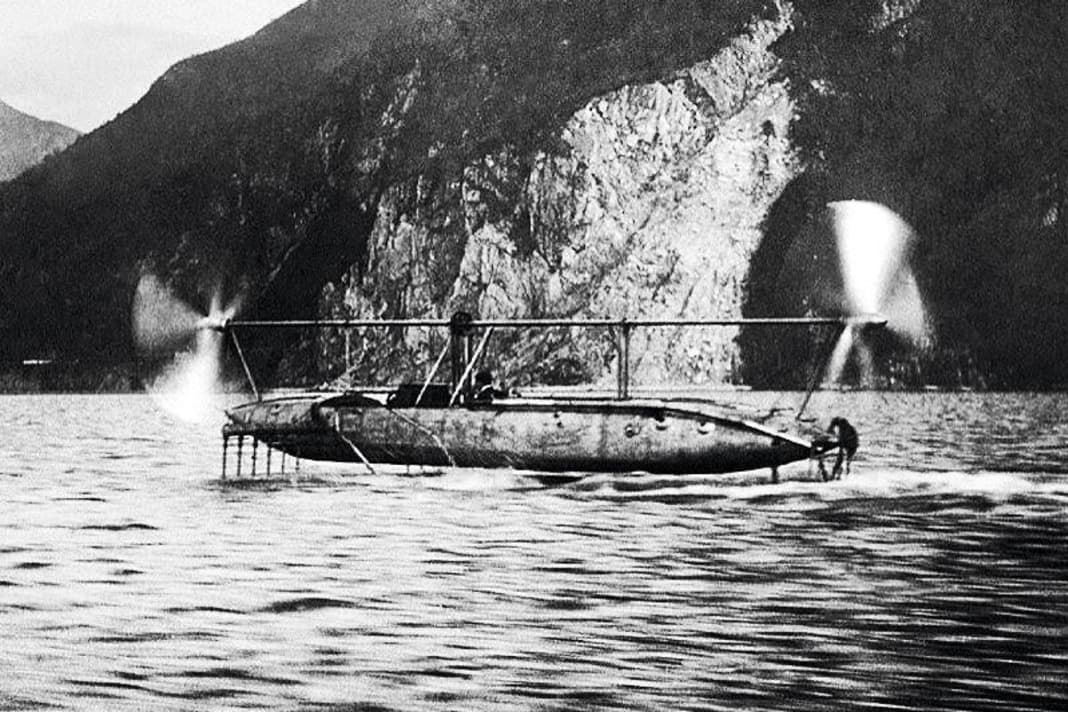

This ground-breaking invention was followed by a whole series of motorised experimental vehicles, often with a military background. On the continent, Enrico Forlani is regarded as one of the pioneers. The Italian designer developed the first autonomous hydrofoil in 1906. Powered by an engine, it reached a top speed of 38 knots on Lake Maggiore. The vehicle subsequently inspired the US inventor Alexander Graham Bell to build his "HD-4", which set a new world record in 1919 that would stand for more than a decade: 61.6 knots.

The first known use of hydrofoils on sailing boats dates back to 1938. The Americans Robert Gilruth and Bill Carl built a small, 3.65 metre long catamaran with a large V-shaped hydrofoil on a structure under water. The boat can take off in a wind of just five knots and reaches a speed of twelve knots - a sensation at the time. Gordon Baker went one step further with the experimental "Monitor". Even the US Navy was involved in the development of the design. The monohull had ladder foils attached to the sides. Later, converted from a conventional rig to two rigid wing sails, the "Monitor" set a record for sail-powered watercraft at 30.4 knots, which still seems respectable even today.

Frenchman Éric Tabarly plays an important role in the development of foils for sailing boats. In 1976, he converted a Tornado hull into a small trimaran and designed hydrofoils for the side floats and the rudder. Tabarly meticulously experimented with various foils, profile depths and settings and then transferred his experience to the construction of the first real ocean-going foiler, the trimaran "Paul Ricard". In 1980, Tabarly pulverised the transatlantic record set by the schooner "Atlantic" in 1905, with the "Paul Ricard" taking just ten days and five hours to complete the journey.

His compatriot Alain Thébault played a similar role in the further development of the "Hydroptère" tri-foiler as Tabarly. Based on the concept of "Paul Ricard", the trimaran built in 2005 was heavily modified several times and the technology further refined. "Hydroptère" sets two records in 2009: 51.36 knots on average over 500 metres and 50.17 knots over the nautical mile. The speed freaks from France also broke the almost unbelievable 100 kilometres per hour mark for the first time ever. This makes "Hydroptère" the fastest sailing boat in the world.

However, the Frenchmen's records did not last long. After a decade of tireless research and development work, Australian Paul Larson set a new world record with the "Sailrocket 2" in November 2011, which remains unbroken to this day. The asymmetrical sailing device, designed exclusively for speed records, achieved a breakneck speed of 65.45 knots over the 500 metre distance in Namibia; at its peak, it even reached 68.01 knots. Under ideal conditions, Larson also believes that more than 70 knots are possible. Considering how early and how stormy the potential of the record-breaking fighters on hydrofoils unfolded, the transfer of the technology to series production took a comparatively long time. The pioneer was the International Moth class. After a few prototypes were built in Australia at the end of the 1990s, Fastacraft and later Bladerider offered the first Moths on foils. They were initially controversial, but triggered a real boom soon after their market launch - and are regarded as pioneers of the current foil trend.

How foiling works: The battle between lift and drag

The America's Cup 2017 showed that racing with 100 per cent flight time has long been a reality. The cats can undoubtedly be considered the most highly developed sailing boats of all time. However, the transfer of technology from the cuppers to series production will be minimal, as they are too far removed from anything conventional that floats - and the solutions that make it possible to handle the boats at all are too specialised.

While modern sailing achievements are otherwise readily adopted in boatbuilding, quickly and not infrequently without any sense - wing keels or chine edges come to mind - foils cannot be adapted so easily.

Even designer Hugh Welbourn, who, as the inventor of the Dynamic Stability System (DSS), is one of the most vehement advocates of hydrofoil technology, openly states the limits of feasibility: "A foil generates more righting moment and therefore significantly higher loads in the hull and rig," says the Briton. To compensate for this, complex structural reinforcements would have to be built into the boat. This and the profile drawn into the hull would result in a lot of space being lost below deck. The costs would also be significantly higher than for a boat without foils. "For this reason alone, its use on normal yachts is highly questionable."

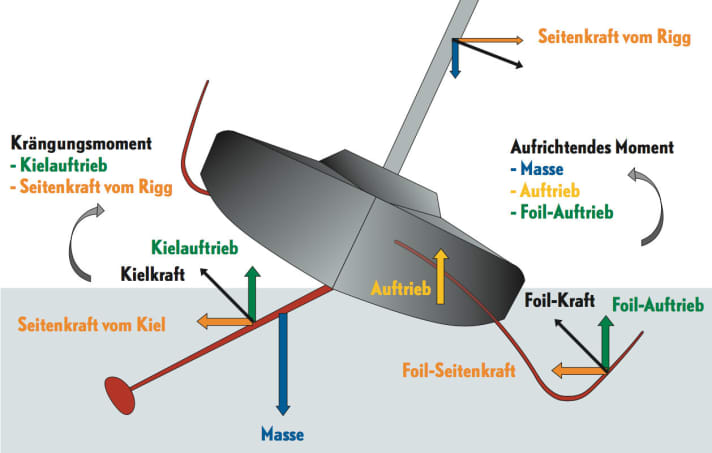

Enormous feat of strength: Many forces work together in a latest-generation Open 60. The foil to leeward and the swivelled keel both generate dynamic lift (green arrows).

At a speed of 20 knots, the hull appendages together generate up to six tonnes of lift - that's around 75 percent of the yacht's total weight.

Various types of foils are possible for modern monohulls. Boats with canting keels, such as the Imoca Open 60 of the Vendée Globe, require a foil that not only produces lift but also prevents lateral drift, as the canting keel cannot fulfil this task. Wings that are angled at the tip produce both lift and lateral guidance.

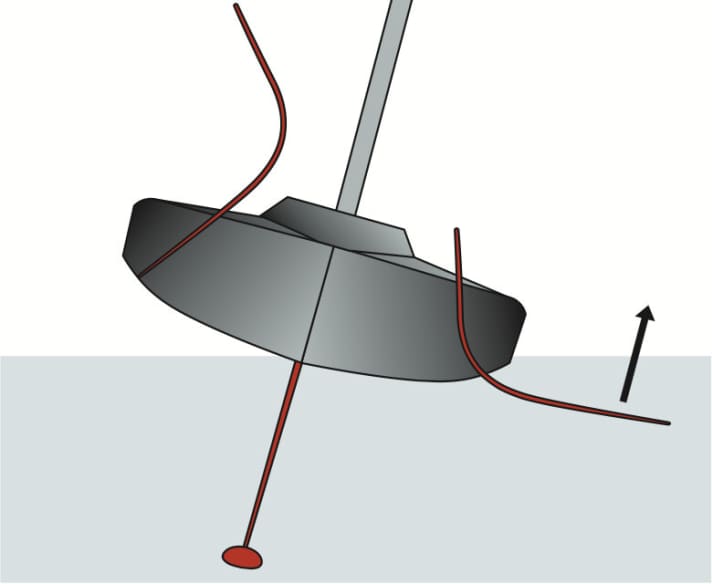

However, if the boat has a fixed, well-profiled keel or an additional centreboard, the drift is already sufficiently minimised. A straight DSS foil is then sufficient. It produces a lot of lift and less drag because the overall surface area is smaller than with L-foils.

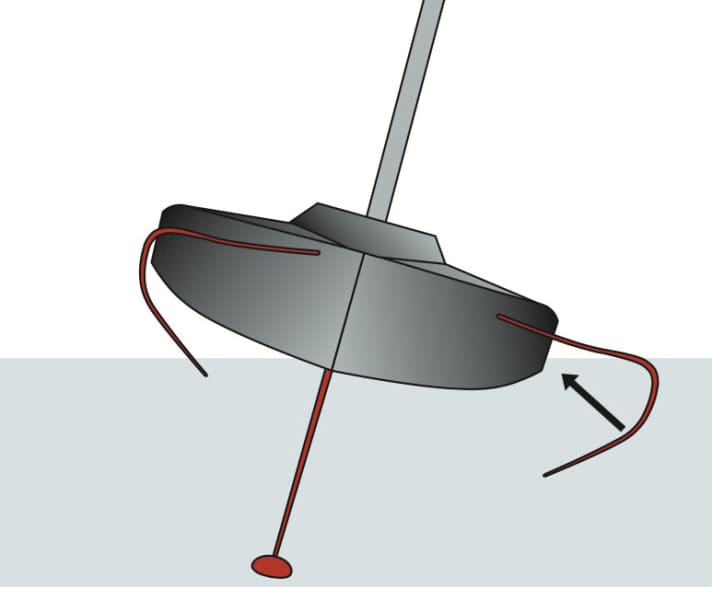

Tip-down or chistera foils, as used in the new Figaro 3, offer a compromise. Like the L-foils, the downward and inward curved wings generate vertical lift and at the same time a force against drift. In the case of the Figaro, the fin of the fixed keel can therefore be very slim. The advantage of the Chistera foils: if the boat sails upright in light winds, the wetted area on the foil remains small and the resistance in the water is less than with DSS or L-foils.

The catamarans at the Cup are so-called three-point foils. They "stand" on three legs, so to speak, on the L- or Z-shaped wing to leeward and on the two smaller foils on the rudder blades. The upwind wing is always raised, not only because this is hydrodynamically advantageous, but also because it is prescribed by the rules of the Cup. Both foils may only be down during the manoeuvres and for a maximum of 15 seconds. This requires a well-coordinated team effort and precise timing from the teams.

This mode of operation is not suitable for everyday use or for the masses. This is why manufacturers of catamarans and trimarans are now tending towards four-point foils for a wider range of buyers; with these, all four hull appendages remain permanently lowered. Of course, four hydrofoils produce more drag in the water than just three, but the flying position is more stable and foiling is easier when manoeuvring. Compared to multihulls, the development of monohulls with foils is made more difficult by one component: heeling. Unlike cats and tris, which are sufficiently stable due to their sheer width, a monohull requires significantly more righting moment to prevent the boat from capsizing. Keel ballast, water ballast or the weight of the crew on the high edge counteract the lateral force. Pounds that are basically the very last thing you need for flying.

Using the foils as a lever downwind provides additional support for the righting moment, but still does not completely neutralise the force of gravity. This is why larger monohulls will probably not be able to take off completely so quickly. For monos, at least for the near future: foiling yes, flying no.

Three small foilers for everyone

One-man high-tech foilers are available from around 10,000 euros. We have tested three foilers for everyone. Here are the technical data and initial test impressions. The full test report is available here for download.

White Formula Whisper

- The mainsail is similar in silhouette to the rigid Cupper wing masts, but is conventionally made of foil

- The jib, which is only three square metres in size, runs on a self-tacking rail. A gennaker can also be used

- The cat can be sailed with single or double harness, but beginners can also just ride out

- The front float segments are thin-walled and must not be stepped on in the event of capsizing; they would break

- The height adjustment is located directly behind the centreboards and is raised together with them. This makes the cat easier to slip

- Hulls and beams are laminated as a single unit. This saves weight and increases the important rigidity

Technical data "White Formula Whisper"

Hull length: 5.40 m

Width: 2.30 m

Weight: 110 kg

Mainsail: 12.6 square metres

Jib: 3.0 square metres

Gennaker: 16.0 square metres

Number of pieces: 50

Price ready to sail: 25 500 €

Waszp

The boom, borrowed from windsurfers, makes it easier to change sides during manoeuvres. The pilot has more space and can squeeze under the leech

- The mast is free-standing, without shrouds. This minimises the risk of injury in the event of a fall over the bow

- The wings can be folded up vertically on land, making the boat just one metre wide

- The hull is wider in the waterline and has more buoyancy than the Moth. Sailing in displacement mode is more stable

- It is sailed without a harness, but the pilot sits far out on the wing and can also ride out

- The rudder and centreboard can be raised for slipping, making it much easier to get into the water

- As with the prototype, a sensor on the bow senses the height to the waterline and automatically regulates the buoyancy on the T-foil

Technical data "Waszp"

Hull length: 3.35 m

Width: 2.25 m

Weight: 48 kg

Mainsail: 6.9 or 8.2 square metres

Number of pieces: approx. 360

Price ready to sail: 10 350 €

iFly 15

- The mainsail in two sizes with its trampoline end corresponds to the high level of development of the A-Class catamaran

- The hulls are made of carbon sandwich. The platform can be dismantled for transport

- The height control system corresponds to that of the Waszp and Motte, including the scanner at the bow

- The centreboards can be disengaged from the height control system and are retractable. The cat then sails like a non-foiler

- The cat is designed for a single harness, but can also be sailed well by two people with a total crew weight of up to 140 kilograms

- The trampoline has a double-layer design with all lines in the space between. It also generates buoyancy

Technical data "iFly 15"

Hull length: 3.35 m x 4.63 m

Width: 2.55 m

Weight: 90 kg

Mainsail: 12.5 or 14.9 square metres

Number of pieces: 14

Price ready to sail: 26 980 €

Future or zeitgeist? What speaks for and against building foilers in series production

Pro:

- Sensation: Hardly anything has more of a wow effect. When a boat no longer ploughs or glides through the water, but literally flies over the waves as if lifted by a ghostly hand, you experience sailing in a new way - and are undoubtedly one of the pioneers.

- Speed: In most cases, the use of foils goes hand in hand with a significant increase in performance, especially in sports catamarans and dinghies, which can reach previously unimagined levels.

- Innovation: Anyone interested in technology and physics will find plenty of intellectual stimulation on the new boats and lively dialogue with classmates. Foilers are usually tinkerers, always on the lookout for improvements.

- Stability: In monohull boats, DSS foils can help to stabilise the boat in rough seas with their buoyancy downwind. However, this does not apply to all designs.

Contra:

- Complexity: Foils produce enormous buoyancy forces. In order to realise these efficiently, the hull, deck and even the rig must be massively reinforced. This increases the construction effort as well as the weight.

- Costs:The shape and construction of the wings are extremely demanding. Even if only a few other adjustments were made to a boat, the price would be at least 20 per cent higher.

- Benefit: Foils increase the operating effort. Their use requires time and experience. In addition, their effect is usually optimised for certain courses and wind windows. However, ocean-going yachts must perform similarly well in all conditions.

- Space requirement: It must be possible to retract and extend the hydrofoils to enable mooring in the harbour. The guides and fastenings below deck are so extensive that the usable space would be massively restricted in the saloon area of all places - which makes no sense for touring yachts.

- Danger of collision: The risk of colliding with a floating object or another boat is greater when the foils are extended. Even when retracted, they still protrude beyond the hull. This makes mooring more difficult when travelling alongside, but also makes it more difficult to come on board.

Picture gallery: Sailplanes in action

When foilers rise out of the water, the images are spectacular. On cats, one wrong steering movement is usually enough for the racing boats to plough back into the water at full speed - which can be life-threatening for the crews of the large regatta cats. We have put together some spectacular foil scenes in a gallery.