No manufacturing process is making such rapid progress as 3D printing. It is therefore hardly surprising that the technology is no longer used solely for the production of prototypes. Hardware manufacturer UBI Major, for example, uses 3D printing to produce parts of its roller systems and bearing cages for guide blocks. Lightweight construction specialist Karver goes one step further. The French company not only uses the technology itself, it now even offers selected fittings as a data set that you can print out yourself. The data records can be downloaded here>>

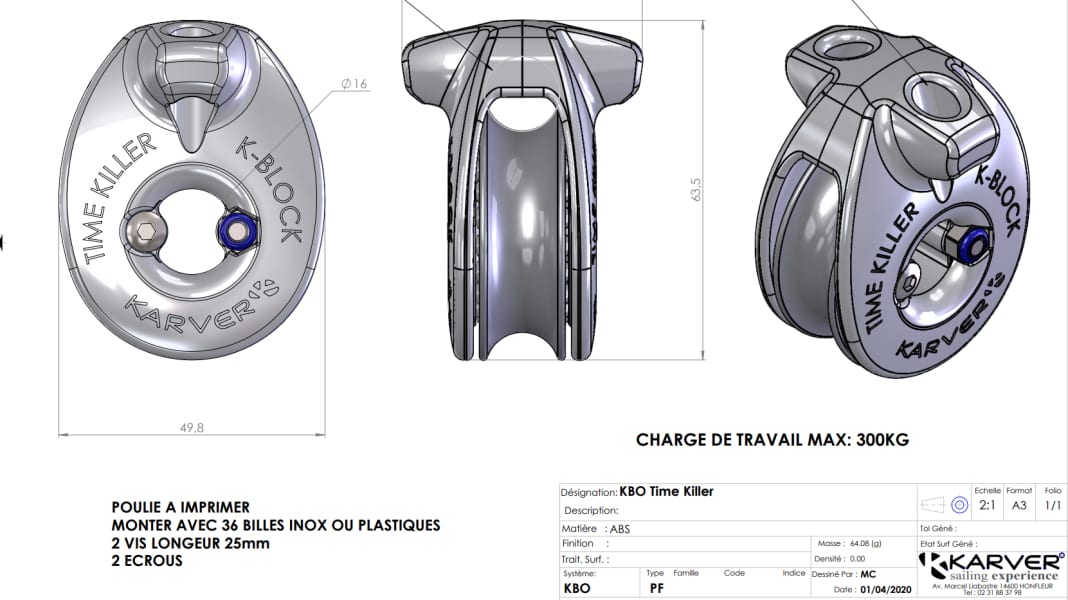

The range currently includes rather simple components such as guide eyes, different sized cleats or chocks for curry clamps. However, there is also a data set for a ball-bearing block with a working load of 300 kilograms. "We want to give our customers the opportunity to print simple parts themselves if required," says Managing Director Tanguy de Larminat . In consultation with dealers and shipyards, the range is to be further expanded in the future.

Colligo Marine had already pursued a similar approach several years ago and exhibited corresponding prototypes at METS in Amsterdam, see here . However, the high-strength materials used at the time could only be processed with industrial printers, which is why the Americans did not pursue the system any further.

Due to the shape and material specifications, the Karver blocks are probably not that easy to print, at least with the FDM devices that are affordable for private users. The abbreviation stands for Fused Deposition Modelling and describes the simplest process for printing plastic parts. Depending on the printer model, it can be used to process various thermoplastics such as PLA, PETG, ABS, nylon or rubber-like TPU. The cheapest printers with this technology cost around 300 euros. If you fancy experimenting, you can use it to make amazingly practical parts for your boat. In YACHT 17/2022, we tried out how it works and the problems that arise.

It becomes more complex when metals are to be processed, which is where selective laser melting is usually used. In this process, a laser burns the component contour into a thin layer of metal powder, melting the material. This creates a solid workpiece layer by layer.

One application is special fittings for individual structures or refits. "We had the top fitting for the new mast of the 60-foot classic 'Varuna' printed from aluminium. This allowed us to design in undercuts and save weight," says Michael Kraske from the mechanical engineering company Werner Kluge in Kiel. As there is now a whole range of service providers, the technology can in principle even be used by hobby designers.

Significantly larger metal parts can be produced using wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM). In this process, a modified industrial robot applies one weld seam after another to create a workpiece. The size is only limited by the radius of action of the robot arm. In addition, any weldable metal can be processed.

An impressive example of its use in yacht building is the 4.50 metre long aluminium keel bomb printed by Dutch printer manufacturer MX3D and KM Yachtbuilders. "The production of casting moulds for the lead ballast is uneconomical for our small series and individual constructions. That's why we produce aluminium shells into which we cast the lead," says Rene Feenstra from KM, explaining the procedure. "However, it is becoming increasingly difficult to find aluminium welders, so the suggestion of printing came in handy," says Feenstra.

A detailed article on the current state of 3D printing technology and its application in boatbuilding can be found in YACHT 17/2022