- Shipyards are increasingly focussing on electric drives

- Overview of drive systems

- Fuel cell systems: the solution?

- Disadvantages of hydrogen

- Vision as reality

- How sustainable are electric drives?

- E-drives promote sailing

- HVO100 diesel: the alternative to electric drives

- Drive systems in comparison

When it comes to sustainability, Magnus Rassy has no need to fear comparison. His house, situated on a hill above the shipyard, is heated by a heat pump. On the south-west-facing roof, monocrystalline solar panels produce electricity on a megawatt scale. And two Teslas are parked in the garage. The older one has been driven by the Hallberg-Rassy boss for eight years; his wife Mellie's Model S also has six years on the battery.

They can be described as pioneers of electromobility, and they are so with full conviction. They would never use a combustion engine again. It is therefore all the more surprising that Rassy does not even offer electric motors for his award-winning cruising yachts, which are built just 500 metres away as the crow flies. "It just doesn't make sense," he says.

More on the topic:

Rassy, who follows technical developments more attentively and open-mindedly than many of his competitors, did not make the decision lightly. If he saw tangible benefits, he would switch without hesitation - just as he has long since completed the energy transition in his private life.

But for the shipyard boss, who invented "push-button sailing" and whose boats have long had double rudders, battened mainsails and other pioneering details, the disadvantages of electric propulsion still outweigh the advantages.

"It may work for dinghies and daysailers," he says. "But for cruising, neither the range, performance nor the charging infrastructure are sufficient." The carefully soundproofed companionways of all models, from the HR 340 to the HR 69, are powered by Volvo Penta or Yanmar diesel gensets, often supplemented by diesel generators on the larger yachts.

Shipyards are increasingly focussing on electric drives

Meanwhile, more and more manufacturers are opening up to electric motors, with only a few, such as Hallberg-Rassy or Bavaria, still producing "diesel only". The Fountaine-Pajot Group, for example, already offers more than half a dozen models with diesel-electric hybrid drive for its catamarans and the monohull yachts from Dufour. Saffier offers an electric option based on lithium batteries for its entire product line up to 33 feet. At Winner Yachts in Neustadt, an electric pod from e-Propulsion is already standard for the two models 8 and 9; those who prefer a built-in diesel will pay a considerable surcharge of 9,000 euros due to the greater installation effort.

So there is no doubt that there is some movement in the sailing yacht market. It would be premature to speak of a boom - especially as the registration figures for electric cars are currently pointing downwards across the EU and could possibly also be a negative indicator for the boating sector. Nevertheless, anyone thinking about buying a new boat today is increasingly faced with the question of what type of auxiliary drive it should be.

Two systems are currently the most widespread when it comes to alternatives to the combustion engine: battery-powered electric motors have become the most common variant for small and light boats; hybrid drives with diesel generators as range extenders dominate for heavy cruising yachts. But these are only the most common solutions at present.

Overview of drive systems

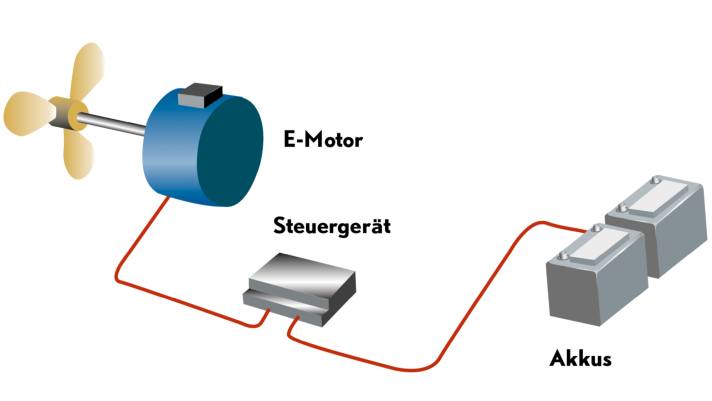

Electric drive via battery bank

On small cruisers, daysailers and light cruising boats up to 32 feet in length, an electric motor powered directly by lithium batteries is sufficient. Even without a generator, ranges of between ten and 40 nautical miles can be achieved with five to 15 kilowatt hours of battery capacity

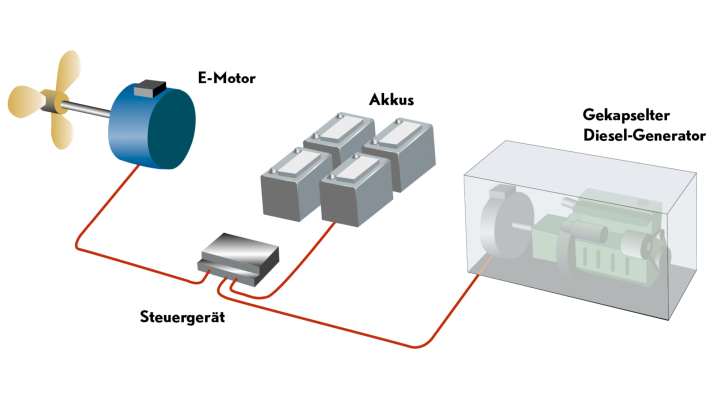

Diesel-electric drive

Larger yachts require large battery banks of 30 to 50 kilowatt hours at 48 volts, which costs a lot of money and has a negative impact on the overall CO2 balance. A diesel generator makes you autonomous from shore power and increases the range in hybrid mode

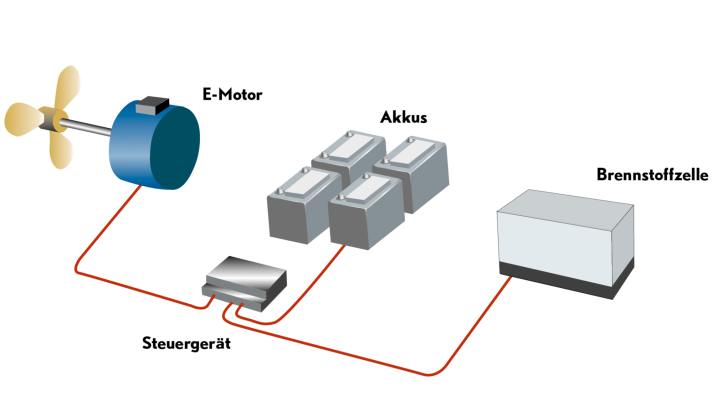

E-drive with fuel cell

The environmentally friendly solution using green hydrogen has so far only been used on superyachts and prototypes. A fuel cell replaces the diesel generator. However, hydrogen electrolysis requires a lot of energy and reduces overall efficiency

Fuel cell systems: the solution?

In principle, they are suitable for all purposes because they are not dependent on large battery packs, achieve relatively good ranges and are CO2-free in operation. The first superyachts are using this technology, but there are also tenders with hydrogen propulsion and the Samana 59 RexH2 from Fountaine Pajot is the first sailing boat to go into mass production.

The most recent project is also the smallest to date. It was created at the Innovation Centre for Sustainability and Production Technology in Nordenham, INP for short. And it has found a world-famous ambassador: Boris Herrmann, himself a professional sailor committed to climate protection with his team Malizia, travelled from Hamburg to the Weser in mid-June especially for the christening of the "H2 innovation".

To demonstrate the possibilities of hydrogen propulsion, the initiators chose a rather unusual test vehicle: they had a 50-year-old LM 23 converted. The museum-quality Bukh diesel engine and its peripherals gave way to a six-kilowatt electric motor from Vetus. It is powered by a fuel cell whose grey casing is the size of a folded-up on-board bicycle: The unit, which produces seven kilowatt hours of continuous power, measures just 75 x 42 x 30 centimetres and fits into the oil locker of the Spitzgatt cruiser, right next to the companionway.

The cell works almost silently, produces only water vapour during operation, no toxic or climate-damaging emissions, and it supplies the electric motor directly with electricity - without the need for expensive and heavy batteries.

It is supplied by a ten-litre industrial gas cylinder stowed in the forecastle. At a filling pressure of 300 bar, this holds enough energy for ranges of between ten and 30 nautical miles, depending on wind and sea conditions. As it is designed for pressures of up to 700 bar, the operating radius could easily be doubled.

As an emergency reserve, the "H2-Innovation" only carries four AGM batteries, each with 240 ampere hours from Victron; enough for docking if the fuel cell should fail. Otherwise, a ship of this type would require at least five to ten kilowatt hours of expensive lithium technology for pure battery operation, and even more for a range of just five to 20 nautical miles.

This shows the advantages of the hydrogen drive. But there is another important plus: the absence of large storage batteries also significantly reduces the environmental impact. This is because it massively reduces the CO2 emissions generated during production, which is particularly important for boats that are only used occasionally. On top of this, the need for raw materials is significantly reduced.

Disadvantages of hydrogen

For the time being, hydrogen has only two, albeit decisive, disadvantages: There is no sufficiently large network of refuelling stations, not even for road transport. There is an almost complete lack of marine petrol pumps throughout Europe - due to a lack of demand. A classic chicken-and-egg problem. In addition, the electrolysis of green, ecologically harmless hydrogen requires an extremely large amount of renewable energy. However, there is a shortage of this everywhere, which actually has a negative impact on the overall balance of all alternative boat drives.

On good days, when the sun is shining and the wind is blowing on the coasts and inland, Germany currently generates around half of its cumulative electricity requirements in a CO2-neutral way, in the best case two thirds. The rest is fuelled by coal and gas-fired power plants. At the current rate of expansion, which is lagging blatantly behind the targets for wind power in particular, this will remain the case for a long time to come. At the same time, the demand for electricity is growing significantly due to electromobility on the roads, heat pumps in the property sector and energy shifts on the part of industry - for example from oil and gas to hydrogen.

Vision as reality

Dieter Sichau, head of the Nordenham Innovation Centre, has therefore taken the LM 23 project a step further and added production facilities for ultrapure water and green hydrogen. He has had the process technology for this built behind Plexiglas. The electricity for the electrolysis is generated by a newly installed solar system on the roof of the hall at Werftstraße 1, right next to the Airbus hangars.

It is more than just a pilot project. For Sichau, this would allow the hydrogen supply to be organised on a decentralised basis: Marinas could use elevated solar roofs to convert their car parks into power stations and use surplus electricity to produce hydrogen. The devices, which whirr quietly away in the INP, could easily fit into a 20-foot container. Instead of waiting for fast chargers at the edge of the harbour, owners could purchase H2 cylinders using the deposit system.

Admittedly, this is more of a vision than a reality at the moment. But the technology is there. "You simply have to think and solve e-mobility holistically. Then it will work," says Dieter Sichau, who was previously head of a leading wind energy company in Germany. He is certainly not happy with the status quo. And the interest generated by the christening of the "H2 innovation" proves him right. The motorised glider already makes the topic of hydrogen propulsion tangible today. From autumn, when testing is complete, it will also be shown at trade fairs.

How sustainable are electric drives?

While it is primarily the energy source itself that has a negative impact on the life cycle assessment of hydrogen, there are several factors involved with battery-electric and diesel-electric drives. First and foremost is the aforementioned "CO2 rucksack", i.e. the energy required for battery production and transport.

While the electric motor is lighter and more compact than a combustion engine, and also requires less maintenance and fewer wearing parts, battery production is a major cost factor. With the current electricity mix, which still contains 30 to 50 per cent fossil fuels, it will take five to eight years before an electric drive even starts to save CO2, even in a car.

Based on the typical utilisation intensity of owner-operated cruising yachts, which is just three to six weeks per year, it is questionable whether the investment will ever have a positive effect on the ecosystem. This is because the cell chemistry of even the best batteries available today loses its storage capacity with increasing age.

The energy density and number of cycles of the currently available lithium batteries is constantly increasing. In five to ten years' time, solid-state batteries will enable a real leap in evolution. But as things stand today, batteries are a wearing part, and an expensive one at that. And as long as they are not charged purely by solar energy or recuperation, i.e. with the propeller running while sailing, they will take a long time, if not too long, to amortise ecologically.

What remains are other advantages: the quiet operation of electric motorisation, the absence of local emissions and the lack of pollutants that are washed into the water via exhaust gas in combustion engines, which is becoming increasingly important, especially on inland lakes.

E-drives promote sailing

And then there is something else, as Christoph Becker from Winner Yachts observes, a kind of soft environmental factor: "The limited range is changing the way they are used," says the shipyard boss. "Boats with an electric drive encourage people to sail longer and more intensively instead of switching on the engine every time there's a lull." He therefore also advises owners not to oversize the battery bank, which saves money and weight.

In principle, the advantages and disadvantages also apply to hybrid drives, which are common in large cruising boats and catamarans. A diesel generator offers additional autonomy and ranges that come close to those of conventional diesel engines. The Viator Explorer 42 DS, for example, which is designed for long voyages, should be able to travel 1,000 nautical miles on a full tank of fuel.

If necessary, the generator supplies the two electric motors directly with power. On shorter trips and when mooring and casting off, the boat runs emission-free using only the energy from the batteries.

For Hendrik Heimer, who founded the brand and helped develop the concept, it is the "best possible type of drive today", especially if it is already taken into account and optimised during the design phase. In fact, there are many arguments in favour of the hybrid. Thanks to large battery banks, an air conditioning system or the water maker, for example, can be operated without the aid of a generator.

This "silent mode" is a real gain in comfort and appeals not only to owners but also to charter sailors, as Fountaine-Pajot boss Romain Motteau confirms (s. Interview). However, the diesel hybrid not only has an immensely high price: between 70,000 and 120,000 euros are due for a 45-foot cruising yacht. Its CO2 balance is also worse than that of the battery-electric drive.

HVO100 diesel: the alternative to electric drives

Firstly, the hybrid requires large battery packs: between 30 and 45 kilowatt hours, to stay with the example given. Their production must first be compensated for. Secondly, it is also less efficient than a diesel engine with a running generator because one more conversion step is required to provide the drive energy, which is why part of the power requirement has to be covered by the batteries at full load.

It is these reasons that are preventing Magnus Rassy from offering alternative drive systems for his yachts for the time being. Especially as there is a simple solution to reduce CO2 emissions to almost zero, even with conventional diesel engines: by fuelling them with HVO100. The fuel, which is obtained from plant oil and fat residues, has been approved by Volvo Penta and Yanmar. It costs only slightly more than fossil diesel and can also make existing boats "green" almost immediately.

Drive systems in comparison

Diesel

- Typical application: Universal

- Examples: All the usual cruising yachts (photo Hanse 410)

- System components: Diesel engine, alternator for charging starter and service batteries, fuel tank, shore power connection

- Pro:+ Proven technology; + Worldwide fuel and service network; + Long range; + Good power-to-weight ratio; + Reserves for electricity and wind power; + Good CO2 balance with HVO100 operation; + Comparatively low costs

- Contra: - Relatively high sound pressure, often in conjunction with vibrations; - Maintenance effort; - Complex installation; - Moderate efficiency (< 35 %)

E-drive with battery

- Typical application: Daysailers, small cruising yachts

- Examples: Saffier Se 24 Lite, Tofinou 7.9, Winner 8 (photo)

- System components: Electric motor, battery, service battery if necessary, shore power connection

- Pro:+ Extremely quiet; + Simple installation; + Local emission-free operation; + High torque; + Highest efficiency (> 60 %); + Silent motor sailing possible; + With fixed-pitch propeller, recuperation under sail possible

- Contra: - Limited range; - Limited charging options; - Limited service network; - Moderate overall CO2 balance; - Still relatively high battery costs

Diesel-electric hybrid drive

- Typical application: High-quality cruising yachts and multihulls

- Examples: Elan E6 (photo), Fountaine Pajot Smart Electric, HH 44 Eco Drive, Viator Explorer 42 DS, X 4.0, 4.3, 4.9, Xc 47

- System components: Electric motor, battery, separate service battery if required, generator as range extender, diesel tank, shore power connection

- Pro: + Extremely quiet when travelling electrically, quieter than with a diesel engine when the generator is running;+ Locally emission-free operation; + High torque; + Good efficiency in mixed operation (> 50 %); + Relatively long ranges thanks to recuperation and range extender; + Silent motor sailing possible

- Contra: - Very complex installation; - Limited service network for electric motors; - High weight; - Relatively large space requirement; - Very high price

Fuel cell drive

- Typical application: Prototypes

- Examples: LM 23 "H2-Innovation", Fountaine Pajot Samana 59 RexH2, Imoca 60 "OceansLab" (photo)

- System components: Electric motor, directly powered by H2 fuel cell, small battery pack, hydrogen tank, shore power connection

- Pro: + Extremely quiet, fuel cell runs almost silently; + Very good overall CO2 balance when using green hydrogen; + Very long service life, low maintenance costs; + Only low battery capacity required as an emergency reserve; + High torque; + Silent motor sailing possible

- Contra: - Lack of hydrogen refuelling station network; - Low to moderate ranges; - Lowest efficiency (< 30 %); - No standard modules available yet; - Lack of specialist staff; - Space required for pressurised H2 tanks; - Very high system prices