Engine check: The engine on a used boat - what to look out for before buying

YACHT-Redaktion

· 23.01.2026

Text from Dr Marie Schneider

The two best days as a boat owner are the days of buying and selling - as the saying goes. If you avoid the typical mistakes when buying, there is a good chance that the days in between will also be fun.

The list of possible defects on a used yacht is almost endless, but damage to the engine, underwater hull and rigging is particularly significant - in the case of cheaper yachts, they can quickly become a total economic loss. What's more, they can quickly become a serious safety risk on the water. Here we focus on the engine and describe non-invasive measures that can provide clues to many obvious engine problems - and some less obvious ones.

More interesting technical articles about motors:

- Step-by-step instructions: How to put the outboard motor into hibernation

- Accident: Engine failure on the flyover - where the fault is often found

- Technology: How fuel filters work and how they function to keep things clean

- Technology: Which motor is the best? E-drives in a system comparison

- Fuels: This diesel is the best for the boat engine

The tests described are extremely extensive. Rarely do prospective buyers and yacht appraisers test engines so extensively. Accordingly, you can expect raised eyebrows from brokers and sellers. However, potential buyers should not let this deter them from meticulously inspecting the engine.

Use these questions to learn about the history of the engine

If you are travelling to view a car, it is best to tell the seller or estate agent in advance that the engine should not be started before the test drive. If you put your hand on the engine, it should be cold - lukewarm means that it has recently been running. All too often, viewings start with the engine already running. If the engine is already warm, compression or starting problems can be concealed.

A conversation with the owner can reveal a lot, for example in terms of driving behaviour. The hour meter alone does not provide any information about the condition of the engine. Were the owners hard-working sailors and did they only use the engine for harbour manoeuvres? That would be an alarm signal. Coking is a common problem on sailing yachts in particular. These are sludgy deposits throughout the engine, which occur particularly when the engine has not been warmed up properly and has only been used at low engine speeds.

Clarify installation situation and previous history

Has the owner carried out the maintenance himself or commissioned a specialised company? Unfortunately, neither is a guarantee of good maintenance. Old invoices can provide an insight into the scope and frequency of maintenance. If the owner has carried out the maintenance himself, you should ideally be able to see a detailed maintenance logbook. Was the oil and filter always changed or was the internal cooling circuit flushed? Hard to imagine, but many owners believe they carry out maintenance very conscientiously, but don't even realise that their engine contains sacrificial anodes that need to be replaced or, depending on the area, changed. In the case of shipyard maintenance, it is possible that only work that was ordered was carried out and not the work that is due for the respective engine model according to the manufacturer. So: Always obtain all available information on maintenance and driving habits. This can be done before opening the engine compartment.

The visual inspection in the engine compartment leads to further questions

The engine and its surroundings should be clean. If the engine is dirty, maintenance has probably not been carried out with the necessary care. If there is no detailed maintenance log, this speaks even more in favour of this.

If the engine bilge looks as if it has just been cleaned, perhaps a few minutes before the inspection a puddle of oil was wiped away. So a little dirt in the bilge is nothing negative.

The next step is to inspect the engine all round: Is it even possible to service the individual components? For example, can the tube bundle of the heat exchanger be pulled out, or is there a bulkhead in the way? If so, this was probably not done. Painted screws without cracks in the paint are also an indication that they have never been opened and therefore the components underneath have not been serviced.

Visual inspection I

Attention must also be paid to traces of salt water leaks. Corrosion on the end caps of heat exchangers or charge air coolers with aluminium housings in particular may require expensive replacement. The exhaust manifold is often the starting point for leaks. If it is rusted through, the only solution is to replace it. In addition to the cost of the spare part, the accessibility of the engine compartment also determines the cost of the repair.

Oil leaks must be considered in a differentiated manner. A little oil on the cylinder head cover of an older engine? Almost normal and easy to rectify. Oil dripping from the flywheel housing on the crankshaft seal? The spare part is a one cent item, but the labour involved is enormous.

The condition and level of cooling water and oil in the engine and transmission are also important. Unfortunately, the latter in particular is often neglected. Milky oil and cloudy coolant indicate that they are mixed. The cause may be a defective cylinder-head gasket, which is a costly and time-consuming repair.

These components are often forgotten during the check

Belts and pulleys also need attention. If there is a lot of belt dust, there may be an alignment problem that cannot be solved by changing the belt.

A wiring harness with damage caused by a tinkering owner or cables that have become brittle due to diesel leaks, a tattered air filter, engine mounts that have become soft or brittle? Signs of a lack of care.

Visual inspection II

However, it's not just the engine that has to work and be installed correctly, but everything around it too. This applies to the entire drivetrain, the electrics on the switch panel, Bowden cables, diesel pre-filter and the diesel tank. How old is the saildrive sleeve? When were the shaft seal and tail bearing last replaced? Are hoses brittle or hose clamps corroded? Are there any signs of diesel pest? Some damage can be recognised indirectly. For example, if there is a pile of wax under the stuffing box, it has been overtightened. This will cause the shaft to shrink. That will be expensive.

If the throttle and gearstick levers resist or jam, the Bowden cables probably need to be replaced. Dark deposits in the sight glass of the pre-filter (which is hopefully present!) indicate microbial degradation products and asphaltenes; a full-blown diesel plague in the tank is then likely. If the filters have only recently been changed, the sight glass must be checked again after the test drive.

The cold start says a lot about the health of the machine

After this careful visual inspection, white oil collection mats are placed in the engine bilge and left there until the end of the test drive. Then we start the engine.

Two engines are usually only found on multihulls. Separate testing allows smoke and noise to be clearly assigned.

A diesel engine should start within one to two seconds - after correct preheating, if glow plugs are present. Any delay is a sign of problems. Once the engine is running, go to the rear and look at the exhaust fumes: On older engines with mechanical injection, light blue or black smoke is normal for the first few seconds, but should disappear quickly. In common rail engines, i.e. with electronically controlled injection, any smoke is an alarm signal.

Engine checks with the machine running during the test drive

Now cast off and test the engine underway. While the owner manoeuvres the boat out of the harbour, you explore the engine compartment again (wearing hearing protection). There are many reasons for unusual vibrations or rattling. It may not even be the engine itself that is the culprit, but the alternator bearings, for example. The nose should also be used: Diesel, burnt oil, rubber, overheated cables, coolant or sulphuric acid from batteries - everything has its own distinct odour. You don't want to find any of these in the engine compartment.

The owner should now be asked to shift from forwards at around 1,000 rpm into neutral and then immediately into reverse. The engine must not stall. If it does, the cause may be the propeller dimensions or the drive train. When travelling in reverse at around 1,500 rpm, observe the engine bearings: they should only move minimally, as when travelling forwards.

Don't be afraid of full throttle - the engine has to be able to handle it

After 10 to 15 minutes, the engine has typically reached its operating temperature. The clutch is then disengaged and the engine is revved up to full throttle. The engine should reach 50 to 100 revolutions per minute above its rated speed. Values significantly above or below this indicate a problem. Now engage the clutch again. Every five minutes, the speed is increased by 500 revolutions per minute until 10 per cent below the rated speed is reached. Drive like this for 30 minutes so that the engine warms up properly. Finally, you drive at full throttle for ten minutes - lever on the table! Full throttle may seem like a lot and the feeling of being "sucked in" on displacement engines is very unfamiliar. However, the following tests are necessary to assess the condition of the engine.

Step on the gas, but do it right

There is no need to worry about damage caused by the test. All diesel engines, including leisure engines, are designed to run regularly at full throttle (for leisure diesel engines about one hour in eight, but at least 30 minutes every 10 hours). If the engine and especially its cooling system cannot cope with 10 to 20 minutes of full load, something is wrong. Then the problem was already there and not just a result of the test.

However, experience shows that you rarely make yourself popular with brokers and owners with tests of this kind, although diesel engines can easily cope with this. However, unrecognised damage is a matter of your own money, and you should politely insist on it.

Check the functionality of the machine at full throttle.

First question: Does the motor even reach its rated speed? If not, it may be overloaded (propeller too large) or there may be another problem. Second question: Is the engine overheating? The cooling system is designed to cool the engine sufficiently at full throttle - even in warm Caribbean water. If the engine overheats during the tests, the cause may be a calcified heat exchanger, for example. This brings us back to the initial questions: When was the coolant changed and was the tube bundle ever descaled? Temperature analysis with an infrared thermometer would go one step further: At the oil sump we reckon with a little over 100 degrees Celsius, at the wet exhaust with around 70 degrees. The temperature differences between the cylinders should not exceed 10 degrees. And a classic stuffing box should not get warmer than 60 degrees.

Third question: Is the engine getting enough air? If you feel a vacuum when opening the engine compartment flap or the engine speed suddenly increases, the engine compartment is too tight and the engine is not getting enough fresh air. This is not an engine problem, but an installation problem.

Fourth question: What about cylinder wear? A compression test is invasive and is rightly rejected by most sellers. An imperfect but helpful test is to check the crankcase ventilation for blow-by at full throttle. If the engine has a closed breather, you can pull out the dipstick a little or open the oil filler cap. A slight air flow is normal, a strong air flow is reason for a proper compression test.

Back at the jetty, the final inspection takes place. Are there any leaks on the previously laid oil collection mats? Professional oil and cooling water analyses are most useful as a time series. As a snapshot, they can show a maximum of impurities (e.g. diesel in the oil) as well as massively excessive signs of wear. Now would be the time to take them.

How the engine test influences the purchase decision

After the engine check, you have a wealth of information and certainly unanswered questions. Is the oil leak found a harmless sign of age, or does the machine need to be overhauled at a cost of thousands of euros? In order to answer such questions, you now obtain quotes for the repair. The same repair can cost different amounts for different engine models, depending on the availability of spare parts. If spare parts are no longer available, sometimes a replacement engine is needed.

At this point, many people reconsider buying a boat. But what is the condition of the rest of the yacht? Can you get it for so little money, and is the overall condition so good that it is still worth buying? It is also important to consider how technically adept you are as an owner and whether you have enough time and leisure to do certain things yourself in order to save money. If so, a high-maintenance engine is less of a problem than if you have to rely on a boatyard for every job. Maintenance and repair costs can quickly reach the cost of a replacement engine.

No-gos: When an engine definitely has expensive damage

A lot of corrosion or dirt, a bad cold start, blue smoke, an oil film on the water, water in the engine or gearbox oil as well as shifting problems that have nothing to do with the Bowden cable are reasons to buy a boat only under very different conditions or not at all.

Of course, there are problems that can remain undetected with the engine check described here. However, if the engine appears clean and well maintained, detailed maintenance logs are available, the cold start is satisfactorily fast and without significant smoke and the engine runs well even at full throttle without overheating, then there is a high probability that it is in good condition.

When you need professional help from a mechanic

If it is a large, expensive engine (from around 150 hp), it is worth investing in a professional engine report. The vast majority of purchase appraisers only offer a functional test (forwards, backwards, once briefly at full throttle). For an engine report, look for a specialist who offers additional tests such as pulling the injection nozzles for compression testing.

Even further tests do not offer complete certainty

The tests described are very extensive. The findings can influence the purchase decision or the price of the used yacht. But the truth is: they still only offer a few clues, and even an invasive engine report with a compression test, for example, does not provide one hundred per cent certainty.

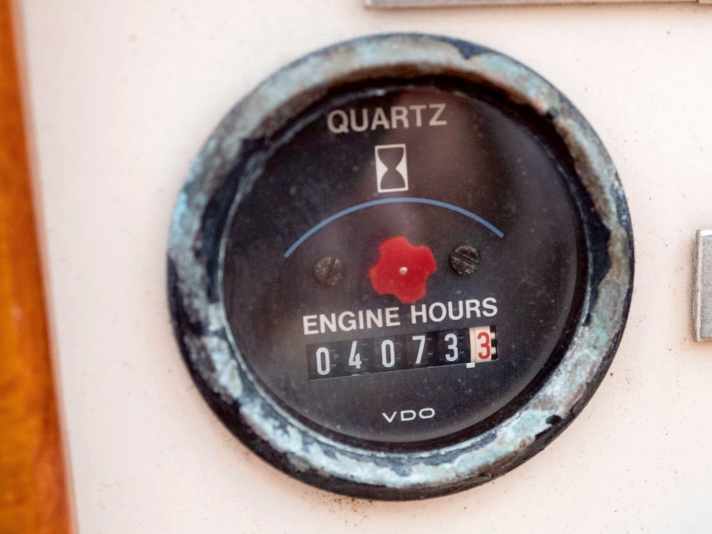

The informative value of the hour counter

It is often said that diesel engines run for a good 4,000 hours before they need their first major overhaul. Unfortunately, this is too generalised - the hour meter is only meaningful if it is known how the engine has been driven. When operated correctly, engines can also run for 8,000 hours without an overhaul. A serious problem with leisure boats, especially sailing yachts, is running at too low engine speeds and too low engine temperatures. To prevent coking, diesel engines must be run hot and at a sufficiently high speed. Ten minutes of operation for mooring and casting off at 1,000 rpm will send a diesel engine to a premature grave.

Buying a yacht ashore

It is possible to carry out a cold start on land. To do this, the impeller is removed (it must not run dry) and the engine is then started. It can run for some time without cooling so that the basic function can be checked. If the engine has been winterised beforehand, any antifreeze from the exhaust tract must be collected so that it does not get into the environment. This is not particularly practical, and all the other engine checks that are part of a test drive cannot be carried out on land. It is therefore better to go into the water for the engine check.

Dr Marie Schneider on the boat diesel course from BoatHowTo.de

Who is behind BoatHowTo.de?

Nigel Calder and Dr Jan Athenstädt developed the original English-language engine course, which I adapted and expanded for German-speaking countries. Due to my activities, formerly as a yacht broker and now as a boat purchase consultant, I am familiar with the concerns of first-time owners and the typical pitfalls.

Can boat owners manage without any knowledge of the engine?

Conditional. I am constantly confronted with customers for whom the engine is a black box ("It's best not to touch it at all!"). As long as the financial means are available, a specialist workshop is within reach and appointments are free, this doesn't have to be a problem. But I always tell them: The engine is one of your most important crew members and needs the same attention as you and them. My aim is to reduce fear of contact and get people out on the water safely and with confidence.

Does the course only cover maintenance work?

Not at all. The course starts from scratch so that all participants are brought up to the same level of knowledge. In over 100 lessons, not only is the maintenance of all components shown, but the functioning of diesel engines is also explained and troubleshooting is discussed. In a mixture of workshop sequences and theory lectures with animations, we go into great depth so that even professionals can learn something new. Also in terms of the drivetrain, tank and filter installation and exhaust system.

For which diesel engines is the course suitable?

We show the maintenance work on a variety of different models. All makes, models and engine sizes work according to the same principle. Whether with or without turbocharger, whether shaft or saildrive, whether mechanical or modern with control unit. So if someone is only in the process of buying and not yet an owner, they can still benefit from the course and transfer the knowledge to their future engine.

When does professional help become indispensable?

If the owner has the will, the necessary tools and the workshop manual, the specialist workshop only comes into play at a late stage, for example when the machine needs a major overhaul or when highly complex or high-precision components are involved.

The online course

Good maintenance and driving habits are essential for a reliable engine. The online boat diesel engine course from BoatHowTo.com offers a comprehensive solution for boat owners who want to better understand and maintain their engines themselves. The offer includes over 10 hours of video material in more than 100 clearly structured lessons on operation, maintenance, troubleshooting and repair. Price: 299 Euro