Anyone who has been sailing their yacht for a long time has usually come to terms with its idiosyncrasies. This also includes outdated navigation electronics. In the days of mechanical pointer instruments and

monochrome LCD displays, longevity was a more important selling point than an exuberant range of functions, and from today's perspective, the manufacturers have done a good job in this respect.

Some device series withstand the ravages of time so well that systems from the 1990s are often still in service on used boats. A good example of this is the ST50 and ST60 series developed by Autohelm and later taken over by Raymarine. Protected from excessive UV radiation under the sprayhood, the displays often still work flawlessly after 30 years. Systems from B&G and Silva/Nexus have also proven to be extremely durable.

Also interesting:

However, spare parts are rarely available. This becomes problematic as soon as one of the transducers, which is much more exposed to the elements, stops working. The failure of the wind sensor, log or echo sounder is often the reason for a complete modernisation of the electronics. Over the years, their connection to the displays has changed significantly, which is why they cannot simply be replaced with current models. Sometimes there are converters or replacement transmitters from third-party providers. However, these solutions are not cheap and the rest of the system remains old and therefore at risk of further failures. This can also be seen on the second-hand market. On online platforms such as classified adverts, significantly more old displays are offered as used encoders.

But even if everything is still running, there are good reasons to consider a retrofit. Even if longevity has not increased across the market in the last 20 years, technical development has continued. Thanks to bonded displays, fogged LCDs are a thing of the past, larger displays and better menu navigation ensure easier operation despite additional functions, and colour displays provide a clear presentation.

Desire for additional functions

Old instruments are often stand-alone solutions that can only exchange data to a very limited extent. Communication often takes place via an NMEA0183 interface or manufacturer-specific cabling. In contrast, practically all current systems work with a bus based on NMEA2000, see page 67. This not only simplifies the cabling, but also ensures cross-brand compatibility of transducers and displays and, with the appropriate equipment, also enables the integration of chargers, battery monitoring or the execution of switching functions via the plotter. Only anemometers and autopilots cannot be easily mixed. They require special calibration routines and are therefore dependent on a suitable instrument or a plotter from the same manufacturer, depending on the model.

A change of ownership and the desire for additional functions are further reasons for the switch. In our example, the last two points come together. The newly acquired X-332 was built in '97 and is equipped with a log and plumb bob from the ST50 series and an ST6000 autopilot from Autohelm. Over the years, an additional multi-function display from the ST60 series and an e7 plotter from Raymarine have been retrofitted. A Simrad radio with AIS transponder was only recently added. However, the current owner lacks a wind instrument. In view of the considerable age of the systems, a complete modernisation of all transducers, the plotter and the autopilot would be obvious, but on the other hand the devices work perfectly and a complete renewal would cost significantly more than 5,500 euros.

What is available? How does the system communicate?

To determine which other options are possible, an inventory is necessary. The best thing to do is to grab a pen and make a sketch of the existing equipment and wiring. The diagram, which is actually obligatory for yachts built to CE, can serve as a basis, but rarely corresponds to reality after several changes of owner.

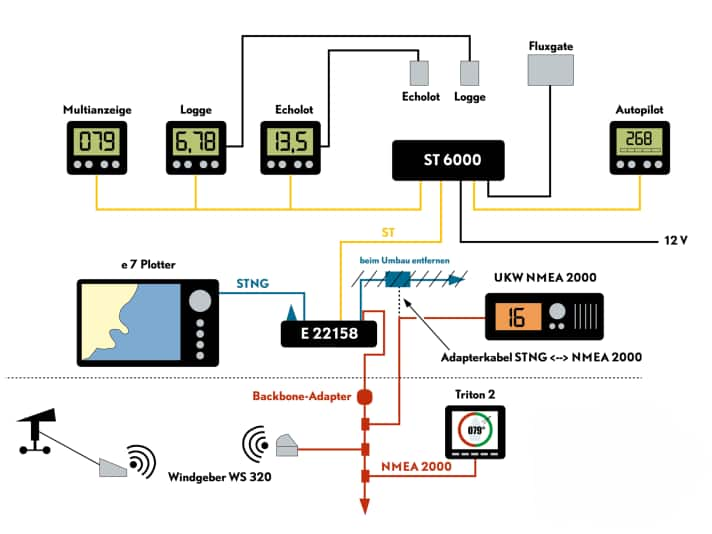

Inventory in the example case

In our case, there is no shipyard sketch. Detective work is therefore required: the log, plumb line and autopilot communicate with each other via the original Seatalk bus, whereby the transducers are connected directly to the displays or the autopilot's course computer. The ST60 multifunction display also worked with the Seatalk bus, but has the newer, flat connector format and, as can be seen when looking into the instrument console, is spliced to the bus with Wago terminals together with a Raymarine GPS antenna - not pretty, but functional.

The e7 plotter only supports the current Seatalk NG bus from Raymarine and the radio requires NMEA2000 data. This means that three bus systems with four different connectors are on board. That sounds more confusing than it is: the previous owners have already installed an E22158 converter that translates between the Seatalk and Seatalk NG bus so that the plotter, autopilot and display can talk to each other.

Another plus point is that there are no older devices with an NMEA0183 interface. This eliminates the need for an additional translator or multiplexer. The Raymarine equipment is also very helpful, as the manufacturer not only pays attention to the backwards compatibility of its devices, the possible combinations of device generations are also documented in great detail in the support area. This is by no means the case with all competitors. For example, owners of older B&G instruments based on the Fastnet bus, such as the H2000 or H3000 series, find it much more difficult to replace a failed transducer or to link the system with current devices.

Play through the possibilities

The almost 30-year-old example system could even be extended with a wind measuring system from Raymarine. However, the current transducers deliver twice as many pulses per revolution and cannot be calibrated directly with the existing ST50 instruments.

The simplest solution would be to install an i60 wind display instead of the old ST60 multifunction display. The device can be connected to both the modern Seatalk-NG and the old Seatalk bus and can calibrate the current wind sensor. However, it requires a wired wind transmitter. The latest version of the wind transmitter, called RWS, cannot be used without further upgrading, as an Axiom series chart plotter is required for calibration.

The ITC-5 converter from Raymarine is also unsuitable. The box can be used to connect old transducers with analogue signals to new Seatalk NG displays. This would make it easy to update the displays without having to replace the hull passages for the log and echo sounder. However, the ITC-5 cannot connect current transducers with Seatalk devices.

Seatalk-NG and NMEA2000 speak the same language but use different connectors. This means that NMEA2000 displays or transducers can be connected with a simple adapter cable, which has already been done with the VHF device, opening the way to use any other NMEA2000-based combination of wind transducer and display. For example, the Triton2 system from B&G. The advantage of this is that the WS320 wind transmitter is available as a wireless version, meaning that no mast cable needs to be pulled in and the cable connection for rigging and de-rigging is also eliminated. In addition, the Triton2 display is a multifunctional display that also offers a quasi-analogue wind rose with the Sailsteer view and can calibrate the wind sensor.

In principle, the GNX wind system from Garmin, which is also wireless, is also an option. It is comparatively inexpensive, offers a very good quasi-analogue wind display and consumes little power thanks to the monochrome display. However, as a multifunctional display, it offers fewer options.

Raymarine itself currently only has the older Microtalk set consisting of wind transducer and handheld remote control in its programme as a wireless variant. This means that an additional i70S display would be required for the desired range of functions with wind display. As a result, this upgrade solution is more expensive than the B&G version.

Structure of the bus systems

To understand how the Seatalk-NG system can be expanded to include NMEA2000 devices, it is necessary to take a look at the structure of the bus systems. Both NMEA2000 and Seatalk-NG or Simnet, which is occasionally used by B&G and Simrad, utilise the CAN bus standard commonly used in mechanical engineering and the automotive industry, but differ in terms of the plug connections. They all have a central line called a backbone, to which displays, encoders and other devices are connected via T-pieces with a so-called track, drop or device cable. The cables have four poles and transport both data and power. Only consumers with high energy requirements need an additional power supply.

In the case of NMEA2000, the cables and connectors of the backbone and device connection are basically the same. As the power for all connected devices flows via the backbone, a slightly larger cross-section is generally used.

With Seatalk-NG, the device and backbone cables have different colours. It is important for the function of all three networks that a terminating resistor is present at both ends of the backbone and only there. It is normally screwed onto the cable as an end cap. Simnet also offers variants that are integrated in the power connection or in the wind sensor.

Two paths lead to the goal

In our case, the radio is connected to the Seatalk-NG backbone via an NMEA2000 to Seatalk-NG cable. To connect further NMEA2000 devices, this branch must be converted into part of the backbone. There are two ways to do this. The official variant is the backbone transition cable from Raymarine, which has the appropriate connector for the Seatalk NG backbone at one end and an NMEA2000-compliant MICRO-C connector at the other end.

The cable is plugged into the Seatalk NG backbone instead of a terminating resistor, which can then be extended with NMEA2000 T-pieces and cables. The missing terminating resistor is fitted as an NMEA2000 version at the end of the new cabling.

Another, less attractive variant can be realised with the existing adapter cable to the radio. To do this, make sure that it is connected directly in front of one end of the Seatalk NG backbone. Then remove the terminating resistor of the Seatalk NG system behind the junction of the radio and transform the radio connection into a part of the backbone, which now has NMEA2000 connectors thanks to the adapter cable. The radio and all desired extensions can then be connected via a T-piece. As long as there is an NMEA2000 terminating resistor at the end of this branch, the system is electrically OK. The unused connection of the Seatalk-NG backbone line is not a problem, it just needs to remain dry.

Regardless of which variant the owner chooses, the necessary adapters are available from specialist dealers for around 45 euros as a cable or for around 30 euros in the form of a compact double plug. You only need to pay attention to the gender of the NMEA2000 side if an existing NMEA2000 backbone is to be connected. When setting up a new NMEA branch, it does not matter whether you start with a male or female coupling. Only the terminating resistor needs to be provided. If you start with a socket, the resistor must also be a socket and vice versa.

Partial modernisation brings new functions and future-proofing

The good thing about the E22158 converter is that it translates in both directions, so the wind data is also available in the old Seatalk network, which means that the ST6000 autopilot will also be able to steer according to the wind angle in future.

The double-sided transmission also makes the instrument system future-proof. If the logging or echo sounder transducer fails, it is possible to install a current Airmar DST810 combination transducer in the Seatalk NG or NMEA2000 version. This combines both functions and can be calibrated both via the Triton2 display and directly on the transducer via Bluetooth. It also feeds the data into the Seatalk network via the converter. With the partial modernisation, the instrument system is well equipped to be fitted with the latest technology or expanded piece by piece. The costs depend heavily on the hardware required. In our example case, they are around 1,400 euros for the wind measurement system and the cabling. If the Seatalk to Seatalk-NG converter was not available, this would add around 150 euros. All in all, significantly cheaper than a complete replacement.

Instrument systems such as those from Silva/Nexus can be converted to NMEA2000 in a similar way using the GND10 converter box from Garmin. There are a few options for Fastnet-based systems, see page 68. NMEA0183 devices can also be linked to Seatalk or NMEA2000 networks using a multiplexer, which is generally suitable for older AIS receivers, VHF radios or GPS receivers or on-board PCs. For plotters that only have an NMEA0183 interface, there is generally hardly any up-to-date chart material available, so they are ripe for replacement anyway.

The next major investment is likely to be an up-to-date plotter mounted in the cockpit or the connection of a tablet, as the availability of wind data also increases the desire for laylines and other sailing functions. Thanks to the NMEA2000 standard, a whole range of options are also available for this.

Inventory checklist

- Which displays/plotters are installed? (manufacturer, model, year of manufacture)

- Which transducers are available? (wind, log, perpendicular, compass)

- Which bus system is used? (Seatalk, Simnet, NMEA2000, Fastnet)

- Is there an autopilot? (model, connection type)

- Is AIS available? (receiver/transponder, connection)

- Which component should be replaced/extended?

- Can existing encoders still be calibrated?

- Are there already converters/multiplexers in the system?

- Is the cabling documented?

Interface or bus

The difference between NMEA013 and NMEA200 and the advantages of the current standard.

DNMEA 0183 and NMEA 2000 were developed by the National Marine Electronics Association to enable communication between different navigation devices. However, despite having the same name, they are fundamentally different. NMEA 0183 is based on serial communication like the RS-232 interface used on PCs in the past. It is a point-to-point connection in which one device (the "talker") sends data to up to four receivers (the "listeners"). The data is transmitted in ASCII format and can therefore be read in plain text using a terminal programme.

NMEA 2000, on the other hand, is based on the industrial CAN bus standard (Controller Area Network). It forms a real network to which up to 50 devices can be connected simultaneously. The data is transmitted in compressed binary format, allowing the protocol to process significantly more data with higher update rates. NMEA2000 is also bidirectional. Each device is given a unique address and can both send and receive data. Each data packet sent is confirmed by the recipients and an automatic retransmission is carried out in the event of errors.

In contrast, NMEA 0183 is unidirectional - one device transmits, others receive. If a device wants to both transmit and receive, it needs separate outputs or inputs for both directions. In addition, there is no addressing: each receiver listens to all data and must decide for itself what is relevant. If an additional data set is to be transmitted, for example the true wind calculated from wind incidence, wind speed and boat speed, the data must be re-sorted and summarised. This is why NMEA0183-based systems usually have a central processor or the wind instrument takes over this function; it then requires separate inputs for wind data, log and, if necessary, the compass heading. This makes cabling confusing, especially as there are no standardised couplings.

NMEA2000 only requires one main line called a backbone, which serves as a data highway. All transducers and displays are connected to this line via a T-piece and device cable and thus also receive power. As the plugs are also standardised, the cabling is very simple and clear. Most devices are compatible with all manufacturers.

More widely used systems

Silva/Nexus, FDX

Depending on the configuration level, the instrument system works with a server and, like some older Furuno displays, uses the FDX bus. With the takeover of Nexus by Garmin came the switch to NMEA2000. The GND10 converter, which is also used for the Garmin wind sensor, translates most of the data in both directions, which is good for expansion with NMEA2000.

B&G, Fastnet

Before the introduction of the H5000 displays, B&G used its Fastnet bus, which is not compatible with NMEA2000. The H5000 Fastnet interface can only translate data from the old system into the NMEA2000 network; it cannot be used to integrate new encoders. If you want to do this, you have to switch to an expensive server from the English manufacturer A+T Instruments.

Simrad, Simnet

The Simnet bus data corresponds to NMEA2000. However, the system uses significantly thinner connectors. Devices with this system no longer exist, but it was used by some shipyards in combination with other NMEA2000 instruments, as the thin connectors simplify installation. Simnet can be converted to NMEA2000 with a simple adapter cable.

NMEA0183

These are usually individual displays that are not really networked with each other, but can only pass on their own data, for example the wind direction to the autopilot. Real networks require a server that summarises the data from the sensors and creates a stream from it. This is also possible with an external multiplexer.

Tablet as daughter

How instrument data can be transferred to a smartphone.

n the bus system, displaying water depth, wind data and AIS information on the plotter is no problem, but practically all crews also have smartphones on board or navigate using a tablet. The latest plotters from Garmin, Raymarine or B&G are equipped with WLAN ex works and can be more or less completely mirrored to a mobile phone or tablet and operated using the app that matches the device.

However, navigation apps such as Navionics and the like cannot be supplied with data in this way. You need a network connection with TCP/IP or UDP connection modes. This requires an external Wifi gateway. The very compact gateway from Yachtdevices is ideal for pure NMEA2000 systems. If you have different standards such as NMEA0183 and Seatalk on board, you can choose from a large number of multiplexers with gateway, whereby the Miniplex from Ship Modul and the devices from Actisense, Yachtdevice and Digital Yacht are the most widely used. AIS transponders such as the EasyTRX3S from Weatherdoc can also send data directly to tablets and smartphones.

What exactly can be displayed depends on the app. Navionics can only process depth and AIS contacts. Savvy Navvy also offers wind and course data. Customised instrument displays can be put together with NMEA Remote. Integration is even more extensive with the Orca app. However, it requires its own gateway, the Orca Core.