Anyone strolling through a marina in the USA will probably be surprised to see a jet of water splashing out of the hulls of the moored boats every few minutes: the cooling water from the air conditioning systems. "That the Americans even cool their boats when they're not in use", marvels many a European.

However, cooling is not the main reason for permanently running air conditioning systems, which also produce electricity costs that often come close to the cost of lying down. Rather, the reason is a problem that is much more pronounced in the USA and the tropics than in Germany: humidity. If the yachts were not permanently dried by air conditioning systems, the leather and fabric upholstery would quickly become mouldy.

Alongside corrosion, moisture is one of the biggest enemies of every boat owner, as it forms a good breeding ground for mould. If the boat is left unattended for long periods and no precautions are taken, it will become increasingly damaged.

Humidity: what's behind it

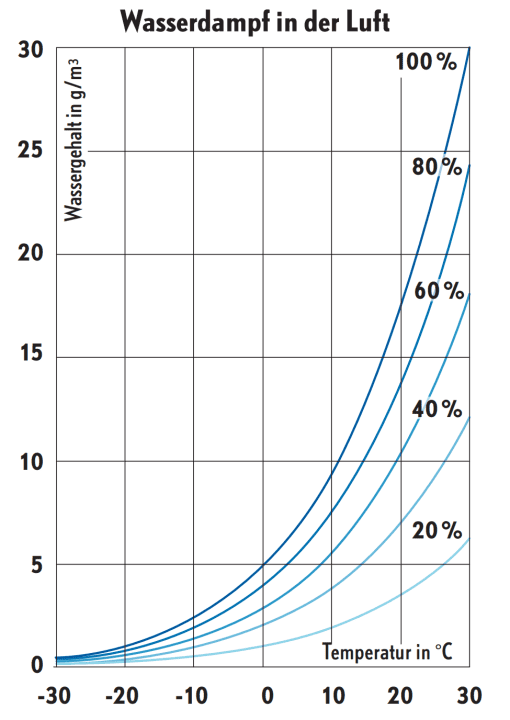

Measuring is knowledge, and a little theory can't hurt when it comes to managing moisture in the boat: The warmer the air, the more water it can absorb. As a result, the relative humidity changes with the temperature. The value is given as a percentage; at 100 per cent, the air is completely saturated. If the air is heated, the relative humidity decreases. If, on the other hand, the temperature drops when the air is completely saturated, water condenses and can no longer be bound in the air.

This effect causes moisture on the inside of the side wall, for example. However, it can be used to remove moisture from the air, as in a condensation dryer or air conditioning system.

Especially in cold outside temperatures, there is a risk of getting wet in the boat. In order to take targeted action against moisture, it is crucial to know how much water is contained in the air on board. This is measured with a hygrometer. As the value is only informative in conjunction with the temperature, a thermometer is often integrated into the measuring device. To prevent mould growth, aim for values below 60 percent relative humidity.

The colder the air, the less moisture it can absorb

The climate in Germany is much drier in summer than in the tropics, and humidity is often not an issue. If the owner checks on the boat every fortnight and airs it thoroughly, the climate on board remains within reasonable limits.

The temperature fluctuations between day and night are also very low. In summer, the average general humidity is 62 per cent. In winter, however, it is a different story at 68 per cent, and precautions should be taken. The difference of six per cent may seem small, but it crosses the threshold from "slightly humid" to "too humid". And that can be fatal.

If the yachts have also been used in autumn and then lie unattended on land or in the water for months in winter storage, the damp air in the ship is left to grow and mould and sparks have free rein. Every yacht constantly collects moisture in its interior anyway, whether through leaks, condensation, rain or even the air breathed by crew members, as each person excretes around 2.5 litres of liquid every day, which is dissolved in the air.

However, air is only able to absorb this moisture to a limited extent. The higher the temperature, the greater the capacity of the air. At an air temperature of 20 degrees and a relative humidity of 80 per cent, the air carries 13.83 grams of water per m3 . If the temperature drops to 14 degrees at night in autumn without heating, the air can only absorb 12.07 grams/m3 and is then saturated. This means that the air has to expel 1.76 grams of water/m3. It condenses.

This "dew point" as the point of saturation is already reached at just under 16 degrees, and the moisture condenses in the form of condensation inside the ship. Usually on objects that are colder than their surroundings, so-called cold bridges such as hatch frames. The direct consequences of excessive humidity are corrosion and discolouration of the wooden surfaces and clear varnish. Moisture also often penetrates upholstery and makes it smell mouldy.

How mould develops in winter

Three things are necessary for mould to grow: it needs a breeding ground (which is already present on most objects due to body oils, skin flakes, etc.), moisture (mould grows from a relative humidity of 70 percent) and a temperature of at least 10 degrees, ideally 30 degrees.

Particularly in autumn and before winter storage, meticulous care should therefore be taken to ensure that no water remains in the bilge and no condensation remains behind the fittings. The less water there is on board in liquid form, the less can become gaseous during the winter and condense in the air.

The ideal humidity level is 50 per cent at 20 degrees

The ideal climate on board is the same as in the house, with an air temperature of 20 degrees and a relative humidity of 50 per cent. However, anything between 45 and 60 per cent is still in the green zone. If the air is too dry, however, the dust particles lack the binding element. Bacteria, viruses and microorganisms then have free rein to enter the human respiratory tract.

Moisture from people or cold bridges

But maintaining these humidity levels is not easy, especially on board. When sleeping, cooking, showering, washing ... Water is constantly being released into the air. And when the temperature fluctuates, such as when the heating is switched off, the relative humidity rises at the same time as the temperature drops.

To avoid cold bridges as places where condensation water collects, ships should be well insulated. Unfortunately, if the shipyard has not taken good precautions, it is often difficult to insulate the ship properly. Good ventilation and thus the removal of moisture is then all the more important.

It is often enough to have a constant draught of air running through the ship during winter storage to remove the moisture. However, this is not always possible in outdoor winter storage and when living on board. The air should then be passively or actively dehumidified.

Passive dehumidifiers

Passive dehumidifiers can always be found in supermarkets and DIY stores in the autumn. There are different versions, but they all work in the same way: One Salt granules is placed in a bag or as a tablet on a grid above a collecting container and removes moisture from the surrounding air (hygroscopic effect).

These are usually granulated Calcium chloride. The white crystals are made up of calcium and chloride ions, which have a strong hygroscopic effect. The moisture from the environment and the granules form a chemical compound, creating a hydrate. When the granules are saturated, the water drips into the collection container below.

One kilogram of calcium chloride can hold up to four litres of water and dissolves in the process. The granulate or tablet can be replaced and the container emptied.

Active, electric dehumidifiers

Significantly more effective, but also more expensive in terms of power consumption, is a Electric dehumidifier. These appliances not only dry the air, but often also heat and clean it. Three systems are common: Condensation dryers with powerful compressors, adsorption dryers with a zeolite desiccant and small models with a Peltier element.

Condensation dryer

Condensation dryer work in a similar way to air conditioning systems: humid air is sent through cooling fins and cooled down until the dew point is reached. As cold air is known to absorb less moisture, the water condenses and drips into a collection container. Although condensation dryers are very energy-efficient, they are also loud, heavy and only really effective at temperatures of up to 15 degrees.

If the ambient temperature is around five degrees, such a system can no longer work effectively because it does not have much room to cool the air before it reaches freezing point. According to the manufacturer, the Trotec TTK 24E model is suitable for rooms up to 15 m2 and removes up to ten litres of water from the air every day.

Adsorption dryer

In an adsorption dryer, the humid air is first drawn in through a filter and passed over a rotating wheel full of zeolites. These are silicate-containing minerals (e.g. clinoptilolite) that attract moisture like a sponge. The moisture collected from the room is then removed from the desiccant by an in-built heater and "regenerated".

The moist air now bundled in the dryer is cooled down with the air drawn from the ambient room and the water it contains condenses. The now dry air is reheated and leaves the dryer around ten degrees warmer than the ambient temperature. In contrast to the other models, the adsorption dryers are much lighter, quieter and more efficient due to the lack of compressor and refrigerant. Effective even in cold temperaturesbut also consume more electricity. As a bonus, the zeolites clean the air of odours and bacteria.

Dehumidifiers can also be operated automatically

Whether condensation or adsorption dryers - both types are available in different sizes, switch off automatically as soon as the water tank is full and also have a hose connection through which the collected water can be channelled directly into a sink and outboard. Some systems have a hygrostat and can be operated in automatic mode so that they switch on when the relative humidity rises above a set value.

In recent years, a number of new developments have come onto the market that score points with lower power consumption and better humidity control. The Meaco DD8L Zambezi adsorption dryer performs best in tests. It extracts up to eight litres of water a day from rooms up to 40 m2 in size.

No other appliance also allows the desired relative humidity to be set via the control panel. Once the value has been reached, the Zambezi goes into sleep mode and wakes up briefly every half hour to check the humidity for five minutes.

Thermoelectric dehumidifiers

For smaller tasks, a very energy- and space-saving dehumidifier with a Peltier element, such as the Pingi Vida, is often suitable. Dehumidification is thermoelectric: heat is extracted from the soldering points in a conductor circuit consisting of two different metals and the air is cooled by a current flow.

This causes the sucked-in air to condense. However, the performance of such dehumidifiers with a Peltier element is very limited. Although the Pingi model we tested only needs 18 watts, it only removes 250 millilitres of moisture from the air per day.

The simple solution: heat and ventilate

In theory, you can also get rid of moisture by heating and ventilating, just like at home: Use a fan heater or any other heater to heat the air in the boat. Then open the hatches and let the moist, warm air out. The cold air from outside is heated up again and the game starts all over again. Of course, this only works in suitable weather conditions. If it is foggy, the hatches should remain closed.

It also requires constant or at least frequent presence on board, which is rather unlikely in winter storage. Heating costs can also rise very quickly, as this method of drying the air is not particularly efficient - the environment is heated for the most part. Only practical for sailors who also live on board in winter and heat anyway.

Dry electrically once, then maintain the level with passive dehumidifiers

The disadvantage of electric dehumidifiers is their high power consumption, which is not negligible, especially when used for long periods. Especially in winter storage and with electricity prices of 50 cents per kilowatt hour, this can add up to two euros a day. In addition, a permanent power supply is required to constantly control the humidity, which is prohibited in many winter storage facilities due to the risk of fire. Before use, and especially when you are away, you should therefore check with your insurance company whether the operation of such devices is permitted.

Although the electric version is the more effective, a combination of passive and electric drying is recommended in terms of power consumption and fire hazards: When winterising, the boat should be dried out for a whole day using an electric dehumidifier after all liquids have been removed. If the relative humidity is then at or below 50 per cent, it is easier for the granulate to maintain the humidity.