Since January 2023, the French-Spanish marine biologist Renaud De Stephanis has been working with the Spanish authorities to unravel the mystery of the orcas and the causes of the mysterious attacks on yacht rudders. Renaud De Stephanis has been researching the behaviour of dolphins and whales since the 1990s and has published over 100 scientific articles. He is the founder and director of the Circe research group ( Conservation, information and study of cetaceans ), which is dedicated to the protection and research of cetaceans (whales and dolphins) in the Strait of Gibraltar.

Equipped with two sailing yachts and inflatable boats, he sails out to the hot zone off the southern Spanish coast every day, where behaviourally conspicuous orcas interact with oars. His goal: to collect orca data in connection with their interactions with boats. In this interview, Renaud De Stephanis talks about the current status of his research, previous results and the best current rules of behaviour for sailors.

YACHT: Since January, your work has brought movement to existing orca research. It was previously assumed that it was only individual animals from the semi-resident Orca Iberica group that interacted with yachts. In autumn 2022, orca conservationists from the Grupo Trabajo Orca Iberica identified 16 animals from the 50 orcas living off Gibraltar that bump into boats. Is that still the case? Or are there more recent findings?

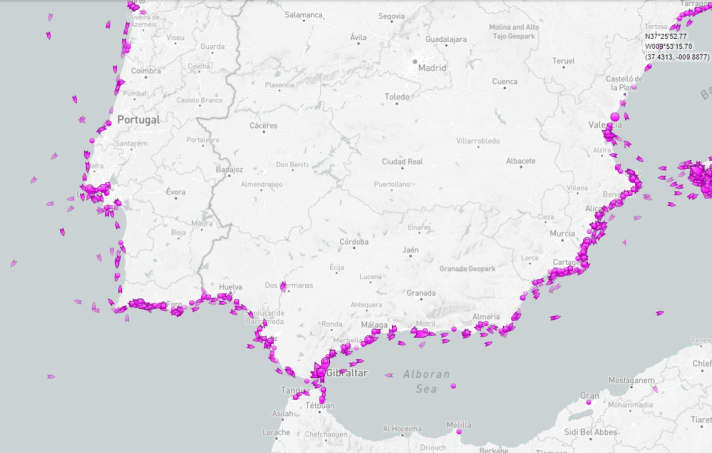

Renaud De Stephanis: Today we assume not just one group, but two groups. This is still a hypothesis, but our observations point strongly in this direction. One group is actively working on rudder blades off the fishing village of Barbate north-west of the Strait of Gibraltar, while the other group is currently active off France.

Where exactly off France?

Off the Gascony north of the Pyrenees, there have been two interactions in recent days that ended with damaged rudder blades. As far as the pack off Barbate is concerned, these animals are now also travelling to the eastern end of the Strait of Gibraltar. We now also have interactions off La Linea north of Gibraltar.

What is the aim of your research?

We want to clarify three issues: We want to reduce the number of interactions. And then reduce the number of damaged rudders. There should be less damage. Thirdly, we are working on explanations as to how the orcas have managed to sink three yachts so far in order to avoid further losses of boats.

The crew of one of the sunken yachts, the "Smousse", stated that the skipper had reinforced his rudder for an upcoming Atlantic crossing. When the rudder blade did not give way, the hull was torn 80 centimetres in length due to the powerful impact of the orca ...

We think along the same lines. A damaged rudder blade never causes a yacht to sink. A damaged hull does. We therefore strongly advise against reinforcing the rudder blade, as this would definitely put a yacht in serious danger. We are also working on technical solutions to prevent the destruction of rudder blades. Pingers, i.e. noise-emitting transmitters, are mostly ineffective according to everything we have tried so far. Our idea is to find a technical solution.

What solutions are there so far? The discussion about the right strategies has visibly changed in 2023, not least thanks to your work since January.

On the one hand, there is the initiative of many websites and WhatsApp groups to publish the location of interacting orcas promptly for all skippers. We are working on making the current location of orcas visible even more quickly in apps, on websites and on electronic nautical charts. Unlike in the last two years, we now know that "engine off" and "lay still" are exactly the wrong reactions. By lying still, you are signalling to the orcas: "Here's your toy. Take it!" Instead, we recommend immediately running away from the herd under engine power and heading for the 20-metre line. We've tried this about 70 times now - only once did this tactic end with a destroyed rudder. That speaks for itself.

This brings us to the interesting question of how the current figures are developing this summer. Is the number of yacht rudders destroyed increasing? Or is it going down?

The figures rose until April. Since April, they have been moving significantly downwards.

How do you explain this?

With a few exceptions, almost all yachts move close to the coast on the 20 metre line. Even off Barbate. This has significantly reduced the number of damaged rudders.

So what is the best tactic at the moment?

In short: know where the orcas are at all times. And then sail very close to the coast on the 20 metre depth line. You're safe there.

How will the figures develop over the course of the year?

To be honest, I haven't the faintest idea. If the sailing yachts continue to stay close to the coast, the numbers will continue to fall this year.

These apps provide the locations of the orcas:

More articles on the topic of orca interactions:

The author's book: