Manfred Jacob actually only bought the "Woge" at the time so that it wouldn't be burnt straight away. And, yes: back then, in 1996, it was a pretty obvious idea. There was peat in the bilge, the planks, frames and floor frames were loose and rotten, the keel beam was broken and the polyester shroud had long since detached from the boat. The dinghy had not been in the water for many years. The "Woge" was a wreck. But Manfred Jacob bought it and even paid 1,000 Deutschmarks for it - including the trailer. Over the years, the graduate physicist and now recently retired programmer restored the "Woge", which was built in Hamburg in 1922, from the ground up. Until finally the mahogany deck shone again.

It is not the first boat in a "pitiful state" that he has rescued. Previously, he had already extensively renovated the "Fram", also a dinghy, which won an award. Although it is always referred to as an I dinghy, even if it is spelt differently. The "Fram" is his high-bred regatta ship. The fact that he still has the "Woge" was not initially planned: "I gave her another four years," says Jacob - "I wanted to sail her as a daysailer on the Elbe, together with my son."

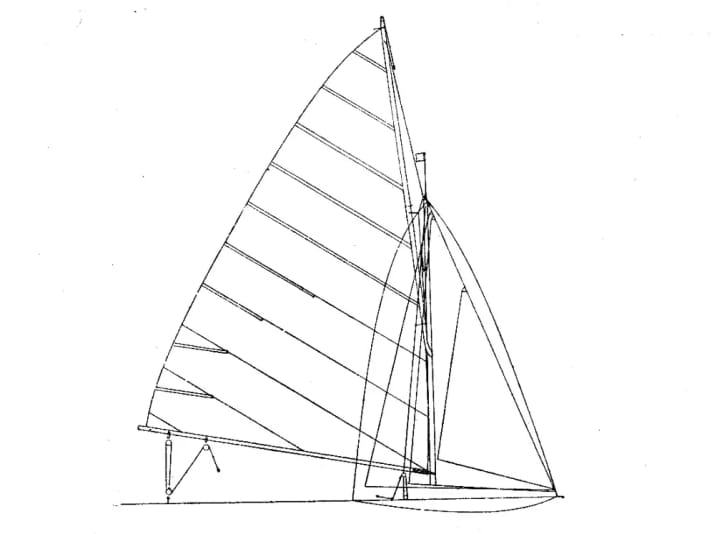

Not really an obvious idea, to be honest, and not just because that son, Marek, was just five years old at the time. A dinghy is a far cry from ships that are usually traded as daysailers today. Even local touring boats such as the Elbe H dinghy are much more comfortable and easier to sail. This is because the J dinghy is an over-rigged racing machine with 22 square metres of sail area; if you have the genoa out, there are four more. Someone once said that if the Elbe H dinghy with a sail area of 15 square metres is a "plough horse", the J dinghy is a "thoroughbred".

The J dinghy "Woge" in every detail:

Manfred Jacob has already achieved speeds of more than 18 knots with the "Fram". At the time, the J dinghy was designed quite differently when it became the first national dinghy class in 1909. Hamburg and Berlin sailors wanted it to be a class of "small, half-decked boats with moderate sails and a crude design, so that they could be given into the hands of beginners as good training boats".

At the time, the J dinghy was intended to be a cheap training boat, but quickly developed into a high-tech machine

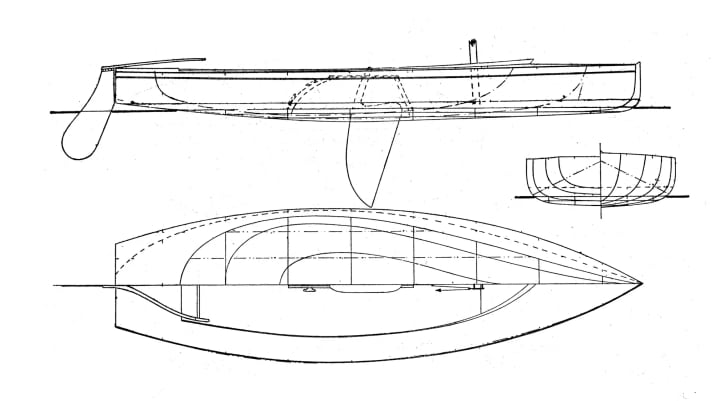

It was intended to be a cheap training boat, and 300 were built by 1915. However, the design class attracted well-known designers such as Reinhard Drewitz, Carl Martens, Willy von Hacht and Manfred Curry and soon developed in a completely different direction. Essentially, the formula was that the length and width had to add up to 7.80 metres, but the boat had to be at least 1.70 metres wide. The rigging was completely optional, but high rigs were never really able to assert themselves against the steep gaff rig.

"It has developed into a high-tech machine," says Manfred Jacob, who has been class president for over 20 years now. "The 22 square metre racing dinghy places the highest demands on the crew. But that is precisely what appeals to the racing sailor, he loves the high school of dinghy sailing," reads a eulogy published in 1941. Before the Second World War, prominent dinghy sailors topped the results lists. The 1938 world champion Walter "Pimm" von Hütschler, for example, and the 1936 Olympic champion Peter Bischoff. Until 1945, it was considered the most demanding dinghy class in Central Europe. Today, the J dinghy is sometimes referred to as the "FD of the pre-war era" because it has similarly high standards as the former Olympic dinghy Flying Dutchman.

Challenging but fast in six force winds

Up to 3 Beaufort, they can also be sailed well by two people. When YACHT visited, wind force six was blowing across the Elbe. The three-man racing crew is definitely needed here, not least because of the constant weight trim on this very sensitive boat. Just like on a Star, the crew hangs as far outboard as possible over the deck, their feet clasped in a harness, which is not original and was never intended to be used.

The third reef is now tied into the fully battened mainsail, which is already a good 60 years old - you can't do much less now without the steep gaff hitting the boom. The headsail is a small jib that normally belongs to a pirate. It's Father's Day, but most of the crews here have stayed ashore, including those on the motorboats. Only a very few sailors have dared to venture out onto the Elbe and against the backdrop of the noble Hamburg suburb of Blankenese; two Lasers are curving through the Mühlenberg harbour basin.

The crew is soaked in no time

The "Woge" sweeps across the Elbe in a wild rush, even without too much cloth, with water sloshing across the deck into the cockpit with every wave. Fortunately, this is already self-draining, so the water is immediately sucked out again, gurgling wildly. Nevertheless, the bailer is always ready to hand. There is a breakwater on the foredeck. It used to be bigger, but Jacob thought it was "ugly", so he cut it in half with a saw, he says. The crew is soaked in no time. For a racing dinghy, the ship designed by Willy von Hacht is nevertheless "good-natured", says Jacob, and now "rather slow". She is supposed to be a daysailer, so she can weigh 80 kilograms more than her sister ships.

In 1937, the "Woge" won its most important prize against 45 competitors - the prestigious "Blue Ribbon of the Lower Elbe", at that time a night race over 60 nautical miles, which started in the late afternoon off Oevelgönne, where people drink their beers in the "Strandperle" today. Through the night, light winds took them past Stade, Glückstadt and Brunsbüttel, and in the first morning light they took the shortcut across the sands to Cuxhaven. The finish was at five in the morning, after a journey of just under eleven hours.

YACHT already reported on the "Woge" in 1924

So let no one say that such a racing dinghy is not suitable for long distances. As early as 1924, YACHT reported how the Woge was sailed from Kiel via Fehmarn to Travemünde on a single weekend. In the evening, the Kiel Fjord remained astern in light winds, and the three-man crew "twisted the neck off the first bottle of port" - they enjoyed the starry sky, and the full moon made the still completely analogue navigation easier.

But then it started to roar and the seas rolling in from the Danish coast got bigger and bigger."There was no turning back for us. So it was persevere or perish."As Fehmarn came closer, the waves reached"The boat was well over a man's height in places and the situation was becoming increasingly precarious when suddenly, on a large, particularly strong wave, the boat ran out of the rudder and ploughed into the water. The mounds of water on both sides of the boat were high. The only thing left to do was to pray fervently and trust in our luck, because if just one of the mountains had collapsed on top of us, the boat would probably never have seen the surface again.

Any other dinghy would probably have arrived in Fehmarn as a rather splintered coffin, if at all.

We would probably have been thrown so far away from the boat that we would never have reached it again, all the more so as it would probably not have laid on its side, but would have turned over completely. As we were about ten miles from the coast, our fate would have been sealed, as there was no vehicle to be seen for miles around."But the "Woge" righted itself again without taking on too much water and made it into the harbour."The boat had survived the effort brilliantly, a testament to Hacht's work. Any other dinghy would probably have arrived in Fehmarn as a rather splintered coffin, if at all."The next day was more relaxed. By Sunday evening, we had travelled from Kiel to Travemünde in twelve hours.

Wrigg instead of motor

Of course, an outboard motor is out of the question for a flat-bottomed classic like the "Woge". But it can be rigged. This is not entirely original, even if it may look like it at first glance - the wrigg dolphin at the stern, which serves as a cleat for the stern spring in the harbour, was retrofitted. The rigging strap is simply in the cockpit and Manfred Jacob uses it to routinely steer the "Woge" through the narrow harbour to its berth. It doesn't bother him that he sometimes receives mild glances from motorised boaters. Elsewhere, he sometimes wriggles through a lock.

Over the years, Manfred Jacob has not only installed new oak floor cradles and a new mast base, but also a new centreboard box - oak on the bottom and the best mahogany from the east of Berlin on top, which survived the years of the GDR in the attic of a boat builder. He straightened the stem, which was sawn off at an angle in the 1960s, so that it looks like it used to. The gaff now comes from another dinghy - Jacob swapped it for a spinnaker after his own fell victim to a Dutch bridge. "I also make every effort to make the 'Woge' look classic," says Jacob, and so he bought old wooden blocks with galvanised iron brackets on eBay. Nevertheless, some modernisation has already been carried out here and there, which is why there is now a furling jib with a plastic furler in addition to outrigger straps. Only electronics are still not to be found on board.

Class of 40 restored J dinghies

Today, the J dinghy class association has over 40 fully restored boats, says Manfred Jacob. Only very few of them were built after the Second World War. Many sailors switched to the much cheaper H dinghy or the faster, Olympic Flying Dutchman. As a result, the German Sailing Association downgraded the 22 racing dinghy to an "age class" and it fell into oblivion. Or even into the fire. In 1978, two gentlemen from Lake Constance restored a famous J dinghy, others followed them, and in 1981 the class association was revived with twelve boats. "There were probably around 100 J-dinghies still sailing at the time," says Jacob, who joined a few years later.

Manfred Jacob also owned a J-dinghy at the time, having discovered it in 1979 in a field behind the North Sea dyke. It was mossy inside, the rigging was missing, as were the transom, deck and centreboard, as were the floorboards. Legend has it that the "Sir Willi von Ottensen", built in 1924, once belonged to his father; however, there is no real proof of this beautiful story.

Nevertheless, the J dinghy virus took permanent possession of Manfred Jacob with this boat. He restored it as a touring boat and took it on summer trips lasting several weeks across the Baltic Sea to Denmark or through the Dutch Wadden Sea in the 1980s. Sir Willi" is now moored at Rottachsee in the Allgäu.

When Jacob sold "Sir Willi" in 1991, he had just landed his next restoration project with the "Fram", investing three years and 1,000 hours of work in her, only to buy the "Woge" a few years later. Along the way, his son Marek was born, now a meteorologist and still a "Woge" sailor - in the summer he was sailing with her and his girlfriend in Holland. In 1998, a photo was taken showing Marek Jacob lying in the mainsail in his oilskin and lifejacket, when the boy was just six years old. "We sailed our first tour back then, ten days on the Müritz, through the canals into Lake Plau and back."

Finland, Elbe, Friesland- the "surge" comes around

They sleep on the floorboards, the tarpaulin is stretched over them as a tent at night, and they cook just like when camping. When reefing or changing the jib, the child, who has been named "super light sailor" and can already swim, steers. Later, the two sail together on the Schlei, the Frisian Lakes, the Havel or the Bodden waters of the Baltic Sea. When Marek was twelve, they travelled to the Åland Islands for the first time - to a family-friendly regatta for small open, traditional boats, the "Raid Finland". Two races were held each day, during which rowing was also permitted. "The rally even attracted people from Hawaii," says Manfred Jacob: "We did it three times. That welds us together."

Finally, in 2012, father and son sailed 400 kilometres down the Elbe together on the "Woge", from Lovosice in the Czech Republic to Magdeburg. The story even made it onto the front page of YACHT at the time.

The first time I capsize, it will be sold

To mark its 100th birthday last spring, the owner gave the "Woge" a new paint job for its hull made of gabon and oak, a shiny golden plaque on the bow and a ceremony with invited guests and a laudatory speech in Mühlenberg marina; signal flags displayed the word "hundred" on the gaff dock.

This makes her the oldest dinghy still sailing in Germany. She is "immortal", says Manfred Jacob today about his "Woge". But the die-hard dinghy sailor also has a clear idea of how much longer he wants to sail her: "The first time I capsize, she'll be sold.

Technical data J dinghy "Woge"

- Designer/shipyard: Willy von Hacht

- Year of construction: 1922

- Length: 6.10 m

- Width: 1.70 m

- Draught with centreboard: 1.15 m

- Weight: 450 kg

- Mainsail: 16.0 m²

- Jib: 6.0 m²

- Genoa: 10.0 m²

Further information at www.j-jolle.org