Researchers have compiled millions of data measured in various ways in the world's oceans in the Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas (SOCAT). It shows that the oceans are an important sink in which C=2 is bound and stored. If this were not the case, more CO2 would remain in the atmosphere and climate change would progress faster.

It is important for climate research to quantify the extent of this CO2 reservoir as precisely as possible. Measurements of the CO2 dissolved in the sea surface, expressed as partial pressure pCO2, are essential for this. Global estimates of the marine CO2 sink, which are also included in the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), are compiled on the basis of this data.

The data situation in Antarctic waters is particularly patchy

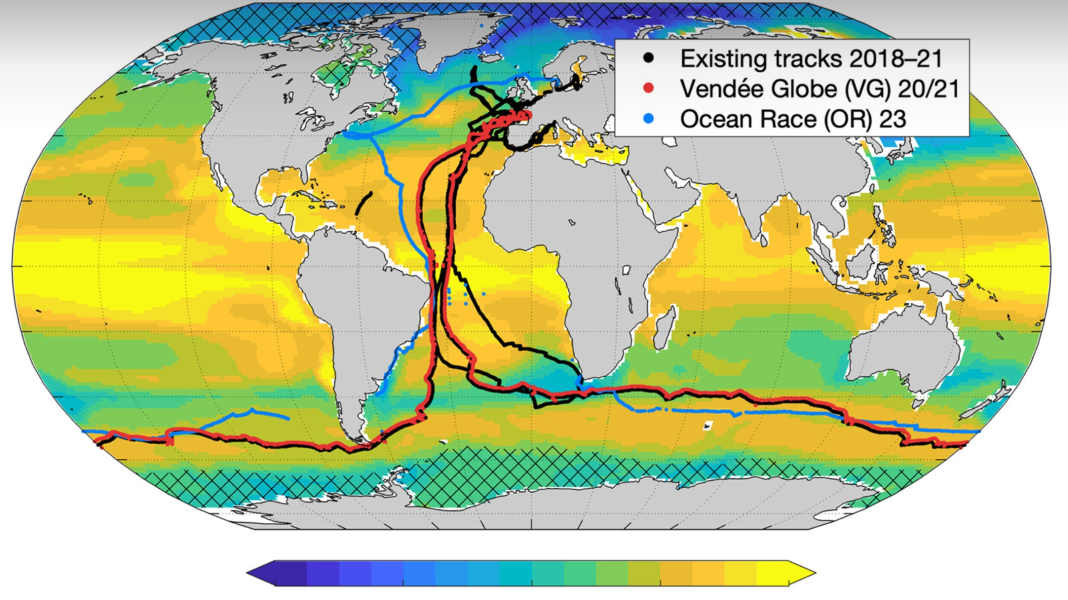

However, the data points in SOCAT only cover a small part of the world's oceans, and the data situation in some key regions, such as around the Antarctic, is particularly patchy. Can the gaps be closed thanks to measurements on board sailing boats?

Scientist Jacqueline Behncke at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology (MPI-M) has been investigating this question together with colleagues from the University of Hamburg, the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel and the Flanders Marine Institute (VLIZ) in Belgium. Their research is linked to a citizen science initiative by Team Malizia: under the leadership of Hamburg skipper Boris Herrmann, sailors have been collecting oceanic data at regattas such as the Vendée Globe since 2018. The initiative is scientifically supported by the MPI-M and GEOMAR and was financially supported by the Max Planck Foundation.

Boris Herrmann and his new "Malizia Explorer":

"With their voluntary commitment, Team Malizia is supporting science and also raising awareness of an important topic," says Behncke. "The collaboration was exciting and productive."

Additional data change estimation of carbon uptake

Behncke and her colleagues had initially shown that the observational data collected by the Malizia team between 2018 and 2021, which included a circumnavigation of the globe, had a major impact on estimates of regional carbon uptake, particularly in the Southern Ocean. A second, recent study has now investigated the extent to which the sailboat data not only changes but improves the estimates of the ocean sink.

To this end, the researchers used the MPI-OM/HAMOCC ocean model to create a global map of pCO2 and tested the extent to which certain measurement strategies led to an estimate of the CO2 sink that corresponds to the model reality. The estimates were generated using a machine learning method.

AI alone is not enough. Human action remains indispensable

The result: if the artificial intelligence only had data on the scale of the current observation network at its disposal, it underestimated the marine carbon sink. The same was true when the researchers also modelled the sampling of the Malizia team and the Nexans-Wewise team led by skipper Fabrice Amedeo between 2018 and 2021.

However, if they included additional measurements from two further circumnavigations, the CO2 sink in the North Atlantic and Southern Ocean became stronger, in line with the simulation. This improved agreement persisted even when the researchers factored in plausible measurement uncertainties.

A systematic measurement offset, on the other hand, worsened the agreement under certain circumstances. "This means that although the quantity of data can compensate for any limited quality to a certain extent, regular calibration and maintenance are essential to avoid measurement bias," says Behncke.

The sailors' actions are helpful, but they do not (yet) cover the data requirements

Although the sailboat data improve the estimate of the marine carbon sink, the long-term development of CO2 uptake in the Southern Ocean is not correctly captured even with the additional two circumnavigations and the trend continues to be overestimated. Therefore, according to the authors, further observations are urgently needed. It is therefore important to stay the course, as sailboat data can help to meet this need.

Pascal Schürmann

Editor YACHT