- The youth cutter and its key data

- Youth travelling cutters from Finkenwerder, Bremen and Freiburg

- At least one capsize per season

- Zero comfort on board the youth travelling cutter

- Life on the youth cutter follows its own rules

- You can still get hands-on sailing on the youth cutter

- Technical data youth cutter

Few things are more irritating to a sailor in search of peace and seclusion than encountering a horde of "cutter Russians" who break into his refuge, noisily and in constant search of any kind of diversion, like a visitation. Then it's easy to overlook what actually unites them, no longer having an eye for the interesting vehicle they are travelling in next door: the youth cutter.

Its ancestor was built in the Imperial Fleet. Naval cutters in various sizes served as transfer boats and training equipment. The next attempt to build a powerful fleet produced further variants. For the training of sailors, for example, the advanced 2nd class naval cutter (K II K). A two-masted sailing boat with auxiliary propulsion by oars for rowing, which on the cutter is called "pullen", sometimes also "ruxen". And a narrower and therefore more manoeuvrable version for the youngsters in the naval HJ, later also called KK on the coast, the abbreviation for Kenter-Kutter.

Cutter sailing was an early part of club life

It is no coincidence that the next part of the story is being written in Hamburg. Between the two wars, the first clubs had already had good experiences with decommissioned naval cutters for their youth work. As a result, cutter sailing became an integral part of club life in this area, and it is not surprising that a colourful collection of these vessels could be found in the clubs along the Elbe after the war.

With the onset of the economic miracle, their members began to seriously consider the future of their youth work. After all, the economy offered new forms of entrepreneurial patronage and many a navy cutter had already been badly shaken, so that calls for new buildings were already getting louder in the 1950s.

Rebuilding one of the existing types was out of the question, as their sailing characteristics were not really convincing. They were all difficult to keep on the helm in strong breezes and rough water. And the drift then increased to such an extent that it was no longer possible to sail at an acceptable speed at the cross.

The Hamburg Sailing Association Altona-Oevelgönne (SVAOe) could already look back on many years of experience with cutters in the mid-fifties. A cutter committee there was looking for ways out of the misery of the variety of types. It was convinced that a solution could only lie in forward-looking standardisation. The young shipbuilding engineer Hans-Peter Hülsen was approached and set to work.

The youth cutter and its key data

The shape of the hull had long been finalised. The wood for two K II Ks had already been cut for several years. Of all the types, this one appeared to be the most suitable with its balanced length-to-width ratio and harmonious lines.

However, Hülsen recognised the weaknesses of the K II K. It was clear to him that decisive improvements had to be made to the rig and, above all, to the lateral plan. In addition, the boat had to be adapted to changing requirements. The naval cutters had been designed for 20-year-old men. As a youth boat, however, they should be able to be sailed by girls and boys under oars as well as under sail.

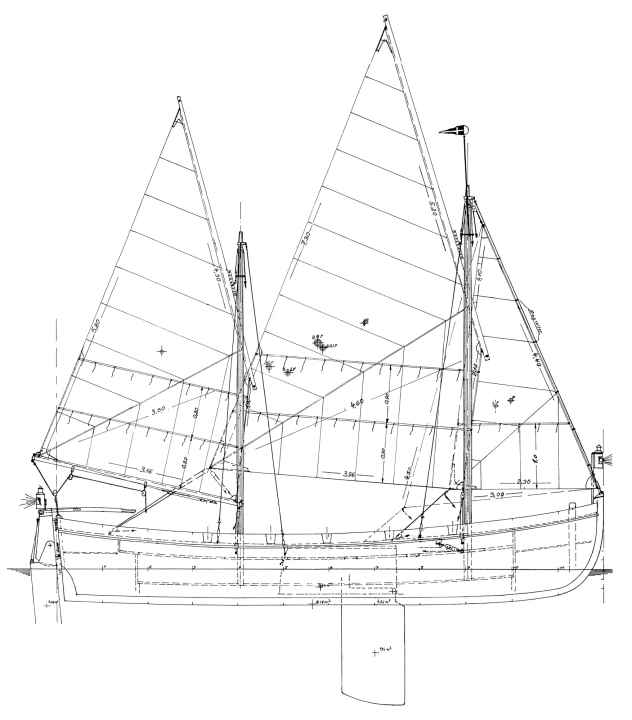

Hülsen's pen was the origin of the Jugendwanderkutter, the later standardised class JWK of the DSV. A Lugger ketch 8.5 metres long, 2.1 metres wide and with an unladen weight of 1.1 tonnes. Five-centimetre thick oak floor beams rest on the 16-centimetre oak keel. The bent-in frames are made of oak or ash, on which the 15 millimetre mahogany or larch karweel outer skin is planked. The oak gunwale forms the finishing touch. Above the solid rubbing strake, an oak gunwale is placed on the outside of the planking, which is called a round gunwale on the JWK. Aft, the boat carries the characteristic heart-shaped transom with the attached rudder.

The youth cutter is an open sailing boat, only the fore and aft peak are covered and offer a certain amount of protection for personal equipment. The crew sits on longitudinal thwarts. The two centre ones can be opened up to provide additional storage space in the forecastle boxes. There are buoyancy chambers under the others. The two stay-rigged masts made of grown wood stand vertically in fittings on the transverse thwarts. The centre of the boat is occupied by the steel centreboard box, with a folding table on each side. In the centre of the forepeak is the large towing bollard made of solid oak, which extends up to the keel.

No winches and rowing instead of motoring

Hülsen has left the centre of gravity of the sail almost in the same place as before, but has harmonised the shape of the cloths and increased them slightly. Its surface area of 31 square metres is divided between the mainsail, mizzen and jib. The boomless mainsail is rigged on two sheets; the respective windward sheet is fully unfurled when sailing. The jib sheet is led directly.

Real manual labour is still the order of the day on the cutter: winches are not used here. And instead of an engine, the crew had to use the five pairs of oars for harbour manoeuvres and on calm days. The technical equipment of the youth cutter was also initially limited to the bare essentials and consisted of a magnetic compass, paraffin position lamps - which have now mostly given way to modern LED lamps - and stable lanterns for inside.

To this day, the design drawings are available to all clubs free of charge

With the naturalness of a Hanseatic man, Hülsen never demanded a fee for his work. The cutters were ordered by the clubs, which still have access to all the design drawings and descriptions from the DSV free of charge. In total, over 40 boats were built, including those with GRP hulls. Most of them were based along the Elbe.

Youth travelling cutters from Finkenwerder, Bremen and Freiburg

There were several concentrations of construction. At the end of the fifties, the first youth sailing cutters were built in Finkenwerder. Master boat builder Johannes von Cölln had already built numerous cutters for the navy and knew what was important.

Ernst Burmester made a great contribution to youth sailing in the 1960s. At his shipyard in Bremen, a quarter of the JWK fleet was built with excellent craftsmanship. Mostly as apprentice labour at cost price. Many clubs were only able to purchase their ships as a result.

In the seventies, several boats were built at Hatecke in Freiburg on the Lower Elbe. At the same time, Rüdiger Schneidereit laminated nine GRP hulls. The mould was taken in 1975 from the Wedel cutter "Kurt Lange", known for its speed.

Plastic versions of the youth travelling cutter were also built

The "Elmsfüer" built by Heinrich Hatecke was the basis for another negative mould ten years later. Boat builder Peter Knief painstakingly prepared the ship to be "plasticised". His shipyard, based in Hamburg-Harburg, was ultimately the only company that was able to build new youth sailing cutters and thus keep the class alive. Eleven cutters originate from the neatly finished mould.

Sail numbers only appeared later, initially large letters were used, which were derived from the boat names. Underlined black Arabic numerals became established. Cutters without an underlined number are not JWK, but naval cutters, classless ones have red numbers or nothing at all in the sail.

A well-sailed cutter is a real opponent for keel yachts of the same size

Designed for a crew of six to nine youngsters, the result is a fast and robust sailing boat that can also withstand a fair amount of wind and exhibits good-natured behaviour. A well-sailed cutter is a real opponent for keel yachts of the same size. On the wind, it wants to be full and driven. With a good schrick in the sheets, it then unfolds its full vitality, which lasts right up to the downwind courses.

Jibing and tacking through the lugger rig takes some getting used to. They always require a certain amount of preparation because two additional stations have to be manned in order to bring the yards, which do not enclose the mast like gaffs in a shoe but protrude from the side, to the new leeward side. The cutter sailors call this manoeuvre "shifting".

As an open vessel, such a boat naturally takes on water in "weather", which is then carried overboard again in a high arc by the oiling crew crouching downwind with the bailer.

In the harbour, the sails have to make room for living

The JWK is a two-masted sailing boat and needs to be sailed as such. It is a mistake to reef the mizzen instead of the mainsail when the wind picks up - at least on upwind courses. Mainsail and mizzen can be reefed twice. However, in practice, opinions differ as to the reasons for this. Because the sails and spars have to be taken down in the harbour to make room for the living space, people like to set off without first clearing all the "rigging".

It's not that easy to capsize a cutter. And if the worst comes to the worst, even the jib can be reduced in size. On many boats, it can no longer be reefed and a storm jib has been fitted instead. Other sails - such as spinnakers and blisters - are occasionally seen on cutters. However, they are not part of the boat, but were brought on board by the crew (with or without the knowledge of those responsible).

At least one capsize per season

The fact that the JWK is still a centreboard boat despite everything has been experienced by numerous crews in a very wet way. At the end of the 1980s, there were frequent capsizes. At that time, the Hamburg clubs had around 25 boats in operation, at least one of which capsized every season. When three boats "lay in the creek" in the summer of 1986 alone, the club leaders were seriously alarmed. In co-operation with a manufacturer of automatic life jackets, self-inflating floats were developed which, when pulled up by the halyard, prevented capsizing and proved to be extremely effective.

The boat is sailed independently by the young crew, whereby the starting age is between 14 and 16 years. Generations of sailors have grown their sea legs as "cutter Russians" and explored their first serious paths in a new community. While sailing, things are very democratic on board, but the cutter skipper - known as the "Kufü" - has the final say, who should not only have more experience, but also the appropriate training, including an SKS licence. If several boats go on a summer voyage together, which is called a "grand tour" on the cutter, an "admiral" - or simply "Aral" - takes over the coordination of this fleet, always on the long line of the board, which waits for regular reports.

As a standardised class of the DSV, the youth sailing cutters form their own starting group at regattas, in which they sail without remuneration. If K II K are also in the same group, the class regulations developed by the DSV in 1964 stipulate that they should be granted two per cent remuneration. During the season, there are also numerous events, some of which are similar to festivals, for cutter crews only.

Many cutter regattas with tradition

There are many memories of the annual North German Youth Sailing Meetings on the Grosse Breite off Louisenlund. As early as 1951, cutters sailed two races a day for a week on the Schlei. The prizes were awarded in front of the sundial in the garden of the boarding school estate by the Duke and Duchess of Schleswig-Holstein in person.

On the Elbe, there were cutter regattas off Grimmershörn, Cuxhaven, in which, among other things, a "Special Prize of the Commander of the Naval Forces of the North Sea" was contested for several years. And for a long time, the cutters sailed as far as Cuxhaven during the North Sea Week at Whitsun.

For the Hamburg Youth Sailing Meeting on the Alster, the cutters were pulled through the canals of the city centre with their masts down. They sailed for the BSC cutter cup on the Elbe, and this is where the summer highlight of the fleet still takes place today with the cutter circus. A weekend spectacle organised by the SVAOe in various harbours on the Lower Elbe. In addition to fun and socialising, there is also a clear competition in sailing and seamanship.

On the occasion of Kiel Week, the navy traditionally organises cutter regattas in five different classes. For a long time, the Elbe clubs were represented by several JWKs. Towards the end of the seventies, this was not possible without lengthy discussions with the rebellious, pacifist-minded youth of the time due to the shore-based parts of the programme on naval grounds.

The cutter scene loves nicknames

Nicknames are one of the apparently indelible characteristics of the cutter scene. Whether "Ruderfuß", "Schampus", "Dreamer", "Batman" or "Major", everyone got used to these names while sailing. Some of them even last after the cutter time: Hardly anyone knows the real name of a "Zewa" in their papers, for example.

Thanking the crews of motorised vehicles after a tow is also one of the rituals. For some unknown reason, however, they always take the form of a single roar of indefinable phrases.

Zero comfort on board the youth travelling cutter

You can't argue about comfort on board the cutter - there is none, and yet the boat exudes a unique atmosphere of enormous appeal. Life is lived under the most important piece of equipment: the large living and harbour tarpaulin. Sleeping is either luxurious on the floorboards or "on the upper deck" on the straps tied together over the dykes.

On days when it's raining cats and dogs, the masts and shrouds get soaked (or sometimes even the entire tarpaulin), and life quickly becomes a matter of taste when everything is wet. The high school of a cutter sailor is to attach his oilskin jacket to the stays in such times so that the rain runs off in between and the sleeping bag stays reasonably dry.

The second most important utensil is of particular importance for life on board: the cooking box, the only watertight place on board and storage space for the cooker, pots and pans and the most important supplies. As this box is mobile, cooking can be done on the jetty in good weather and the subsequent baking can be done in the harbour's own washrooms.

The club's board members have apparently given up the fight against car batteries on board for the obligatory sound system with music.

Life on the youth cutter follows its own rules

"The nice thing about the cutter was that it was our own world, which only worked according to our rules. There were no parents who didn't take us seriously and no one to tell us what to do." Lara sailed for several years on the girls' cutter "Scharhörn", whose crew were also known as the "Schar-Hühner". "And we still did all the things that would have caused a row at home: We took out the rubbish, turned down the music if it disturbed the neighbours, and greeted them politely." Life on the cutters follows its own rules.

What remains are the memories of beautiful voyages, the first exciting trip through the Kiel Canal after a tugboat was finally found at the locks, and the freedom of a carefree life in the company of young people. Being able to share the good things with them, experiencing personal responsibility and getting to know their own limits through the great master: the sea - the fact that the youngsters were able to do all this on the cutters for generations is probably one of the greatest achievements of the clubs.

Of course, a JWK is a boat for trips in sheltered, coastal waters, which Germanischer Lloyd defines as "day trips between nearby harbours along the coast, in an area that is relatively sheltered". Young people make their trips on weekends in their home waters, but during the holidays they are drawn further afield. Since the clubs no longer give orders and commands, but instead have greater freedom and are also utilised, the chronicles are filled with annually recurring negotiations between the board and young people about the extent of the summer tour. Around Funen and Copenhagen seem to be a matter of course, the question is often rather whether in the north around Zealand or not.

When cutters met, other sailors got scared

In the heyday of cutter sailing in Hamburg, when there were school holidays and one half of the fleet sailed around Funen to the left and the other to the right, the infamous summit meetings would logically take place in some harbour or other. A kind of "Vikings are coming" atmosphere spread among the yachts that had arrived beforehand, and even the harbour master only breathed a sigh of relief the next afternoon when everything was not as bad as he had remembered from the previous year.

Today, only five youth sailing cutters from the Elbe clubs are still in operation. But the JWK has introduced generations of young people to sailing. After all, anyone who has paid attention on a cutter and learnt their lesson can sail and, above all, is a team player! And that's not all: the wooden boats are also used to learn how to treat community property with care and the winter work is carried out by the crews themselves under the guidance of experienced "old youngsters". This demonstrates the ability of wood to integrate, as learning these crafts is part of the training and contributes significantly to the cohesion of the crew during the time without sails.

The youth cutter is an exception among the many wooden yachts. The operation of the cutters is orientated towards a clear, targeted purpose and is not primarily for the edification of those who make it possible. The boats are indispensable "workhorses" of the youth department and are in full daily use. It seems that their originality as a cultural asset has not yet really penetrated the consciousness of those involved.

You can still get hands-on sailing on the youth cutter

On the contrary: the ships are constantly being maltreated by new youngsters, which they have to put up with without complaint. The feeling for nautical antiquity, for the most careful handling, must be foreign to the cutter sailor. Probably also because he is currently undergoing training on a rare traditional class.

Because the little Luggerketsch undoubtedly is. With a design that has remained unchanged to this day and which has passed all the innovations of more than half a century without a trace, the JWK is now a real old-timer whose distance from other boats has become even clearer due to rapid developments in recent decades.

In comparison to the modern classes for young sailors who practise competitive sport on the water, here they sail on a lovable dinosaur. Although it has been declared dead several times in its life to date, the surviving specimens are fortunately still quite vigorous. To this day, the cutter's charm lies in the group experience, combined with the now deliberately antiquated handling of the boat. The cutter still offers hands-on sailing.

Text: Ulrich Körner

Technical data youth cutter

Developed in 1958 from the Class II naval cutter

- Design engineer:Hans-Peter Hülsen

- Length over Steven: 8,50 m

- Largest width on the planks: 2,10 m

- Depth: 0,8-2,1 m

- Unladen weight: 1,1 t

- Fock:4.62 square metres

- Light weather jib: 6.31 square metres

- Mainsail: 16 square metres

- Besan:10.41 square metres

- Mast height: 6,0 m

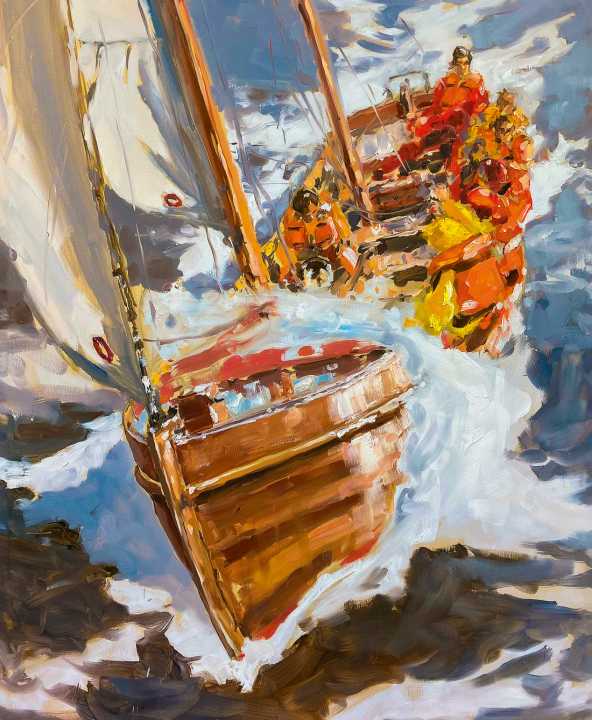

About the artist and author

The Hamburg artist and YACHT-classic illustrator Hinnerk Bodendieck began his sailing career in a youth sailing cutter. He created several paintings about this time, which he says had a strong influence on his later life, and which now hang in friends' homes, clubhouses and Bodendieck's own home. He has collected the most beautiful ones for this story. Many years ago, our author Ulrich Körner carried out extensive research on the Jugendwanderkutter for the Freundeskreis Klassische Yachten, on which this tribute is based.