Those were strange times with strange boats: The wild seventies, the heyday of the then leading handicap system of the International Offshore Rule (IOR), were influenced by a spirit of experimentation and innovation that has only reappeared today in the age of foiling boats and yachts.

This was particularly true of the so-called quarter-tonne models, the smallest of the popular tonneau classes, which were derived from the famous single-tonne models. The quarter-tonne models became a playground for designers - with sometimes visually questionable results.

This boat here, for example, not only screams bright seventies orange in combination with lush green superstructure flanks, but is also a back deck boat with a spoon bow that looks like the beak of a puffin. From the stem to the mast, there is quite a lot of ship, as the rig is so far aft that it could easily pass for a mizzen mast. Behind it, the remaining length of the boat is just enough for the forecastle deck to merge into a curved, wide cockpit. But that's how it was in 1970 - when IOR was being developed and designs were chasing each other and becoming increasingly radical.

During this IOR slime phase, it couldn't be screaming enough; the new formula roof triggered a huge boom in construction and experimentation worldwide. The large single-tonne models that emerged were serious ships; the quarter-tonne models that followed them by the dozen always remained a bit punky. An early contribution from Germany to the sporty pocket cruisers won the world championship and caused quite a stir in the already colourful scene.

The sheet steel boat was light and fully gliding

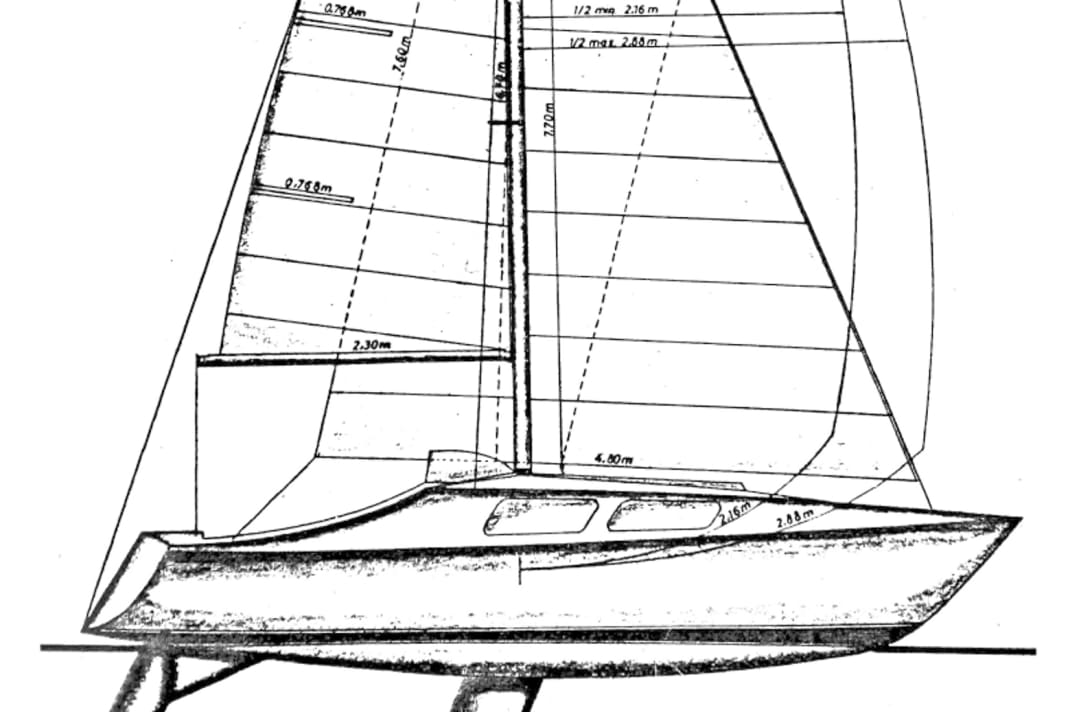

This Listang quarter-tonner, designed by Karl Feltz from Hamburg, belongs to a series of what were once the fastest ships in the world. The exquisite crew won the world championship in 1969 off Breskens in the Netherlands - something that Germans were never to achieve again until the end of the quarter-tonner era in 1997.

Harald Schwarzlose, then navigator and later editor-in-chief of YACHT, remembers: "'Listang' was a collaboration between Ulrich Libor, the Olympic silver medallist in the Flying Dutchman, and Feltz. Ulli wanted a sea cruiser that could glide. Feltz drew a boat whose hull was as flat as a flounder, similar to a dinghy cruiser, the bow round and full as it is today, not sharp like the sea cruisers of the time. The stern was wide and flat, like today's modern yachts, with a sharp trailing edge. The keel was a short fin with low ballast. This was also new at the time. The hull (Ulli: 'light, light, light!') was welded from paper-thin sheet metal on very narrow steel frames standing close together. The yacht scene had never seen such a lightweight construction before.

The Freundeskreis Klassische Yachten calls the Listang the first "consumer yacht", because the small backdecker was later built en masse in GRP (like many other successful quarter-tonne yachts) and offered small cruiser families a space miracle. However, the original Listang was built from steel.

Harald Schwarzlose again: "Even on the Scheldt, the Listang showed its superiority over the other conventionally wooden yachts. The flexible rig proved its worth and the mainsail could be adjusted to the prevailing wind conditions without reefing. We won all the inshore regattas."

All of them! A revolution was taking place here! However, this was felt even more strongly by those members of the yachting community who had not been keeping an eye on current developments in dinghies and the Olympics. Because those who, 50 years ago, as young men, won the world championships of the quarter-tonne dinghies with this probably weirdest of all avant-garde boats, came from the dinghy corner.

Listang unites top crew

Skipper Ulrich Libor - top sailor in the Flying Dutchman dinghy - made a pact with the virtually invincible Englishman Rodney Pattison. Libor won two medals in Pattison's wake (Acapulco and Kiel), and a total of five FD medals were sailed on board "Listang".

"The decision - and the fiasco - came during the ocean night regatta that everyone feared. The wind had picked up strongly and was expected to reach gale force during the regatta. The weather forecast: north-west five to six increasing, in gusts seven to eight."

The legendary FD champ Pattison (twice gold, silver, three-time world champion) may not be on board for the visit, but Harald Schwarzlose and Ulli Libor are enjoying the revival below deck of this bright orange series boat, one of the last Listangs still sailing, like a class reunion after 50 years, even without him.

There is almost nothing on and below deck that owner Karl-Heinz Grünberg has not changed. He got married on board, toured as far as Norway, gave the boat an effective battened boom jib and remodelled the interior several times. But he still has the original sails.

When sailing, you can still feel the special nature of the Listang today. Because the quirky bundle of boats is somehow fun, even if it looks more like a mini-scow than a quarter-tonner - because it invented a dancing gait and the gliding of larger boats. Although this production boat lacks the then almost unknown, extremely flexible 7/8 rig, the funny sail geometry has remained. The huge genoa far exceeds the surface area of the tiny mainsail, which merely acts as a trim tab. Grünberg: "looks like a pirate's main".

Listang: Beautiful sailing is different

"Ulli contributed a trimmable rig that he knew from the Star. The mast could be bent like a bow so that the main opened at the top." Listang works. The huge powerhouse mainsail called the genoa gives the impression that its centre of gravity is directly above that of the ship, pulling it forward with power. Shrewd courses on small waves are clearly a strength, even compared to today's boats.

However, an extreme IOR characteristic of the Listang soon becomes apparent: it pushes early and hard; you always need a little speed and the balance of both sails. If only one sail pulls, control is quickly lost. The Listang anticipates an IOR-typical extreme, but there is another way. The narrow fin keel may be radical, but it is small and the lever is huge. And with a righting moment of 45 kilograms at 90 degrees (measured by YACHT), the boat is clearly in the top league.

"Our biggest competitor was the Dutchman Hans Kortekaas. He sailed a modified Waarschip '725 Vierteltonner', a plywood construction and therefore very light with a displacement of 1.10 tonnes. He coped better with the choppy seas and sailed away. The Listang pitched heavily in the short seas, its rather flat, round bow hitting the waves hard. As soon as we had left the Scheldt and were on the open North Sea, it started to roar. The swell became rough. The cross went as far as the lightship 'North Hinder'." Because the small keel quickly became a typical feature of IOR yachts, yachts often carried centreboards or canards, including "Listang".

During a regatta, the boat's welding points give up

"As navigator, I usually sat below deck and checked our course on the nautical chart. The noise was deafening. The thin metal skin rattled and groaned. Suddenly my feet splashed into the water. We were making water! I quickly located the source: the centreboard box in the foredeck! I stuffed a duffle bag into the opening."

Blackless navigation was mainly based on couplings. "We did have one of those handheld radio direction finders that was supposed to be able to hear Bushmills or Stavanger, but I doubt anyone ever got a proper fix with one of those things. Apart from the radio beacons, you could hear everything."

Pitch-black night on the North Sea. "White foam heads on huge waves. Where was the lightship's blinker? 'Listang' hammered its way through the roar. Gusts of eight! Finally, around midnight, the redeeming call from the helmsman: "Blink ahead!" No sign of the competition. Slowly it dawned on us: we were last." Did the spectacular race to catch up start with a demolished but gliding ship? No, the catastrophe was only just beginning.

"Suddenly there was a loud crunching and cracking noise below deck. Startled, I saw in the light of the torch that the frames in the bow area were beginning to bend inwards. The sheet metal outer skin had torn off and the spot welds had failed. Every time the boat entered a wave crest, the outer skin flapped against the bent frames with a loud bang. The sheet metal outer skin would crack and we would sink in a few minutes. I shouted outside: 'We're sinking!

"I think it's spinnaker time"

Now it was time to get going. Ulli dismantled some of the furnishings, sawed the spinnaker pole into pieces and supported the sheet metal skin from the inside. Later, Peter Schweer came into the cabin with a Puk saw. He continued sawing, smashing and wedging. The flapping and banging of the outer skin stopped! Then the four of us sat outside in the cockpit. I had put my feet up on the life raft lying on the cockpit floor, ready to throw overboard. I couldn't get over the trembling in my knees. Ulli was sailing a little lower now, and the movements of the ship became more bearable."

It's amazing how the small boat reacts to minimal changes in angle. One of the many things that owner Grünberg has changed is the rudder keg. As with the prototype, there is now a balance rudder in the boat. "The downwind course back into the Scheldt was on the cards. Huge wave crests overtook us. Rodney stuck his head out to the companionway and announced: 'Well, I think it's spinnaker time. I thought the guy was crazy. A few dots on the horizon - our competition. No one had set the spinnaker on any of the boats. After an hour, we had caught up with the yachts ahead. Only on one other boat had the spinnaker been hoisted: Hans with his Waarschip! But against 'Listang' it behaved like a lame duck."

Whilst in the lead, there was a misunderstanding about a barrel that needed to be passed. At the mention of this, Libor's facial features still look a little pained today. Which proves once again that navigators can't win races - only lose them. Harald Schwarzlose: "My carelessness almost cost us the victory. But now it was out of our reach. We crossed the finish line triumphantly with the badly battered Listang. Then we lay in each other's arms, laughing and shouting our happiness. We had won the trophy, we were world champions in sea sailing."

Listang goes into series production

When series production began, the later Professor H. Dieter Scharping took care of the GRP structure, and the Listang went into series production with the blessing of Germanischer Lloyd. This was because the "sidewalls-slightly-higher-and-top-on" construction method was new in Germany at the time. It proved to be extremely favourable and created space miracles, so that YACHT was already asking with concern in the seventies: "Are we going to bake the deck now?"

Feltz, Scharping, Blohm + Voss: the original German trio with their Listang project had something of Udo Lindenberg about them. At the beginning of the seventies, Lindenberg also promoted German music with very avant-garde approaches and made it socially acceptable.

"Listang" was even relaunched - as a half-tonner. Fiddling with the formula allowed the boat to grow relatively in IOR, and with more sail area and ballast it now fitted into the larger measurement. What wasn't new was the ability to fly low on the centreboard. They almost won that world championship too. Because the plan was to flatten the others on the centre of the sail, and they had a chance of winning before the long distance, which was rated many times. Ulli Libor: "During the race, we were too fast for a buoy layer who threw a buoy behind us without realising that we had long since passed. But our protest was useless."

Technical data of the "Listang"

- Construct. / Shipyard:Karl Feltz

- Torso length:7,50 m

- Waterline length:5,70 m

- Width: 2,50 m

- Depth:1,20 m

- Weight:1,26 t

- Ballast/proportion:0,32 t/25 %

- Mainsail:8,8 m²

- Furling genoa:19,0 m²

- Spinnaker:46,0 m²

This article first appeared in YACHT 8/2020.