Hardly any sailor does without the wind indicator in the masthead - if you look around a crowded harbour, you will hardly find a mast without the movable flag. It is usually a Windex from the Swedish company of the same name. Launched in 1964 and almost unchanged since then, it has been sold around 1.5 million times to date, according to the company.

In order to function properly, a clicker must fulfil certain requirements. It doesn't matter whether it is a Windex, another brand or a home-made one. It should be light so as not to weigh down the masthead, which is all the more important the more sporty the boat is. And it should work smoothly so that it still indicates accurately, especially in the important low-wind range. The mounting must also be reliable. Quite a few wind vanes have been lost in rough seas or flipped off the pole when the backstay was released suddenly. The pole itself, on which the flag is mounted, should be positioned a little way away from the masthead so that the indicator is not affected by the wind from the mast or the sails.

Clickers read differently during harbour manoeuvres and underway

The first major benefit of a clicker is in the harbour during casting off and mooring manoeuvres. Every crew member can see it and immediately determine which way the wind is blowing and deduce from this where the yacht should be manoeuvred. This makes it easy to teach inexperienced sailors rules of thumb, for example when mooring in pits or with the stern to the pier. Deploy the mooring lines on the side to which the tip of the clicker is pointing first; the fenders are most important on the side to which the flag is pointing. This saves the helmsman from having to ask distracting questions, especially during the hectic phases of manoeuvres.

However, once the sails are set, you need to understand a little more about what the wind indicator shows and why in order to be able to use it optimally. Because when the yacht is stationary or only moving very slowly, as in the harbour, the clicker shows the direction of the true wind, i.e. the actual wind direction. However, if the yacht is travelling, this changes. The wind perceived on board is the result of the airstream and the true wind, known as the apparent wind. This is displayed by the Windex. However, the apparent wind changes its direction and strength greatly depending on the yacht's course, wind speed and speed and often has little to do with the direction of the true wind.

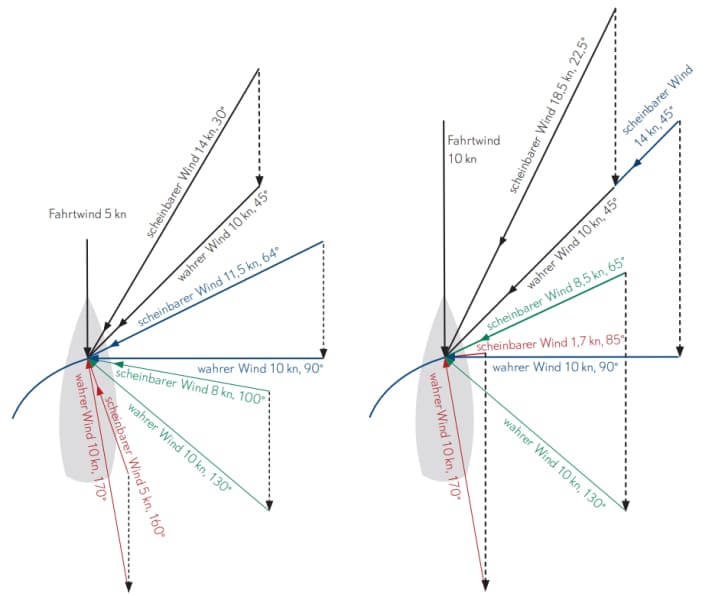

A yacht sails with the apparent wind. This results from the direction and strength of the true, natural wind and the strength of the wind coming from the direction of the course. The apparent wind can change its direction and strength significantly depending on the yacht's course and speed. The diagram on the left shows the apparent wind for four angles of incidence of the true wind blowing at ten knots, the yacht travelling at five knots in each case. The same situation is shown on the right with the true wind remaining constant but the yacht travelling at ten knots. The deviations are obvious.

Indicators help

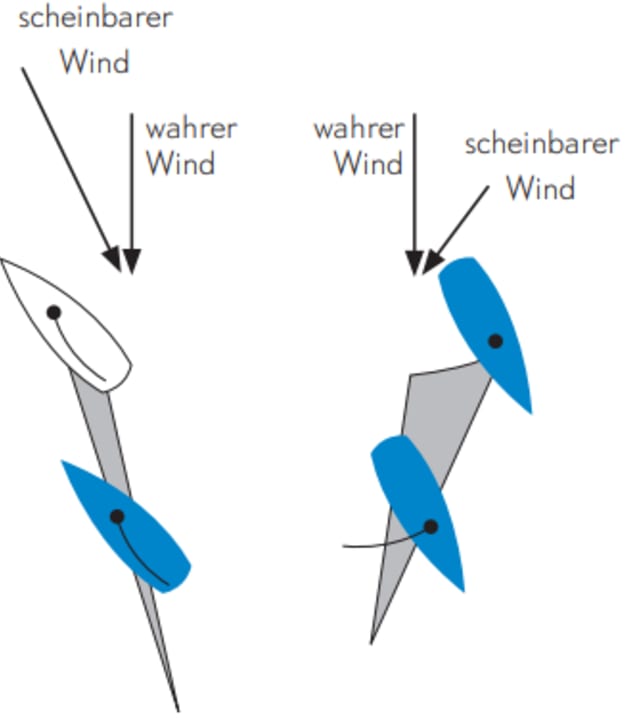

An important tool for using the clicker correctly are the small indicators, which are attached below the vane on many models and can be set to a specific angle by bending them, as with the Windex. When setting them, it is important that the two indicators are symmetrical to the centre line, i.e. that they each show the same angle to it. Which angle is the right one depends on the type of boat, especially the speed. The aim is for the flag of the clicker to be as directly above the leeward indicator as possible on an upwind course.

It is often said that the indicators should therefore be set at 45 degrees, i.e. 90 degrees to each other. But this is wrong and a misunderstanding. Most yachts sail at around 45 degrees to the true wind, but the clicker shows the apparent wind. This is always more favourable than the true wind as the boat sails - the more boat speed, the more acute the angle. A value between 55 and 65 degrees is therefore recommended; Windex even provides a bending template for this. Set in this way, the indicators are a quick and easy visual reference point for the course to be steered. Without them, there would be no reference point and it would take considerably more experience to correctly interpret the angle of the wind vane.

Meaning of the clicker varies depending on the conditions

In principle, the clicker should not be used directly to steer any course. Rather, it serves as a constant, independent comparison, as reassurance for the helmsman. On an upwind course, the wind tapes in the sail and the heel are the most important indicators of the correct course. In strong winds and heavy seas, the clicker even becomes partially useless, as it constantly changes direction due to the constant braking and accelerating of the yacht and the resulting changes in the airstream. This can go so far that the flag gyrates. However, in very light winds, when there is hardly any steering feel in the boat, or when it is raining and the wind tapes are stuck to the sail, the Windex can be the last remaining aid. The following rule applies: if the flag is between the indicators, you are steering too high; if it is outside, you are steering too low. Very experienced helmsmen who know their boat well can also steer according to the degree of overlap between the flag and the indicator.

The clicker is also a good aid to quickly steer the right course again after a tack. Simply drop so far that the flag and leeward indicator are on top of each other.

On courses between upwind and downwind, the Windex is primarily used to set the sails correctly, especially the mainsail. Unlike the genoa, the mainsail is often not equipped with wind tapes. It can then be difficult to recognise whether it is being hoisted too close or too far. One indication of this is when the luff kinks as a sign that the sail is being furled too far. Depending on the weight of the cloth, however, this creasing may only occur very late or, especially with laminate sails, not at all. In this case, the clicker helps again and a rule of thumb: take the main so close that the boom is about 20 to 30 degrees closer than the flag of the clicker. But this is only a rough guide.

Avoid patent jibes with the clicker

The wind indicator and the indicators are more important when sailing in windy conditions. Especially in tougher conditions, with a lot of wind and swell, it can be very difficult to sail the yacht low and avoid a patent gybe, especially if the wind has shifted and the wave direction no longer matches the wind direction. The direction of the waves can then tempt you to steer a wrong, dangerous course. However, the clicker always provides quick and reliable information about the wind angle. If the pointer of the Windex is exactly between the indicators, the boat is sailing flat in front of the sheet. The risk of a patent gybe is then very high if the helmsman deviates even slightly to leeward. It is better to set a course with the pointer above the windward indicator, but in any case pointing towards it rather than towards the centre between the two. The apparent wind will then come slightly to windward and the yacht will sail more calmly and often a little faster than flat downwind. Above all, however, the danger of a patent jibe is averted.

If you actually want to jibe, the wind indicator will again provide good information. When preparing the manoeuvre, you should then steer as described above. Inexperienced helmsmen tend to go very deep, even before the wind, when preparing the gybe. However, this increases the risk of jibing. In addition, the yacht's rolling motion usually increases on this course, making it more difficult for the crew to make the necessary manoeuvres in the cockpit. And the helmsman can lose his footing and lose control.

Helpers in the jibe

After jibing, it can happen that the helmsman loses his bearings due to the hectic pace on board and the change of course. The clicker can also help in this case: keep luffing until the pointer is back above the windward indicator.

Regatta sailors also use the wind indicator as a tactical tool. This is because it also indicates the direction in which you have to expect an opponent's downwinds or how to position yourself in order to give an opponent downwinds and thus slow him down. The following applies on the cross: If the arrow on my Windex points to an opponent upwind, I will receive their downwind. If my Windex flag points to an opponent to leeward, I give him downwind.

This becomes more difficult on deeper courses, especially with very fast boats. An extreme example is the America's Cup. The foiling boats are so fast and generate so much wind that even on deep room sheet courses the wind comes diagonally from the front, only about five degrees rougher than on the upwind course. The covering cone of the sails is therefore to leeward. You have to have sailed past your opponent to influence them. This also occurs with gennaker boats, although not as strongly. The diagram on page 86 shows this case on the right-hand side for an angle of incidence of the true wind of 130 degrees (green), the apparent wind comes from 65 degrees at ten knots of true wind and ten knots of speed.

Electronic control requires exact data

Boris Herrmann is one of the very few sailors who do without a clicker. He relies entirely on the electronics of his Imoca. He has to, as his boat is steered by the autopilot almost all the time. This requires accurate wind data. If one of the components fails, he would have no chance with manual steering, as he has to sleep at some point. No clicker would help him.

However, all other sailors should not rely solely on the so-called wind magnifier. It is certainly possible to steer according to this, but this requires a functioning system. This is because the encoder vane in the mast measures the direction of the apparent wind, as with the clicker, and the wind turbine measures its strength. In addition, the data from the logger is used to calculate the strength of the airstream and thus the direction and strength of the true wind. If, for example, the wind sensor is not exactly centred or the wind wheel or log are measuring inaccurately, the displayed values are useless.

This can often be observed on poorly maintained charter yachts when the values displayed on the different gauges vary greatly. To make sure that the display is reasonably accurate, you can sail under engine exactly into the wind. If the reading on the display is then exactly zero, at least the wind direction on the transducer is correct; however, you do not know whether it is also measuring the wind strength exactly. It is also true here that the transducers in the mast are influenced by the turbulence in the mast. This is particularly strong downwind and can lead to significant deviations in the display during manoeuvres. Relying solely on the electronics can be dangerous. Last but not least, it is also possible for the electronics to simply fail.

Clicker as a useful addition to electronics

However, if the electronics are accurate, there is little reason not to steer according to this. The display can then be set to show the true wind. The direction of the apparent wind can thus be read directly and independently on the clicker without having to press any buttons first.

A wind vane is therefore by no means a rudiment of pre-electronic times, but a useful addition to electronics. The clicker is also the only reliable aid with which the direction of the apparent wind or, in the harbour, the true wind can be determined immediately. It is true that every helmsman should steer according to the wind and intuition. However, this includes a regular look at the masthead.

More on the topic:

Lars Bolle

Chief Editor Digital